La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

+2

Lucius

MARIE ANTOINETTE

6 participants

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La France et le Monde au XVIIIe siècle :: Les Arts et l'artisanat au XVIIIe siècle :: Les arts graphiques et la sculpture

Page 1 sur 1

La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

C'est une exposition, présentée prochainement au Vitromusée de Romont (Suisse), qui me donne l'idée d'ouvrir ce sujet concernant cet art pictural que, personnellement, j'apprécie beaucoup...

Présentation :

Reflets de Chine - Trois siècles de peinture sous verre chinoise

16 juin 2019 - 1er mars 2020

Paysages fantastiques, portraits d’enfants et de concubines, scènes tirées de la vie familiale et de grands romans épiques, créatures issues de la mythologie, représentations de symboles : le Vitromusée propose la première grande exposition présentant un panorama de la peinture sous verre chinoise, une production artistique exceptionnelle et peu connue à ce jour.

La bonne bergère, vers 1760

Image : Collection Vitrocentre

A travers un choix exclusif d’environ 130 œuvres provenant de deux collections privées majeures d’Allemagne et de France ainsi que de celle du Vitromusée, complétées par quelques prêts d’autres musées suisses, l’exposition retrace la longue histoire de la peinture sous verre chinoise : sa naissance au XVIIIe siècle, issue de la rencontre des traditions picturales chinoise et occidentale, sa « mondialisation » via l’exportation, avant de devenir un art populaire au XIXe siècle.

Elle témoigne du goût de la cour impériale chinoise de l’époque, de l’engouement de l’aristocratie et de la bourgeoisie européenne, puis américaine pour les chinoiseries et donne une idée de la vie du peuple chinois, en dehors des classes privilégiées.

Plongé dans un monde exotique, le visiteur découvre un domaine fascinant du patrimoine culturel chinois, et des œuvres d’une extrême finesse d’exécution.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Vitromusée de Romont

INTRODUCTION TECHNIQUE :

Avant de présenter quelques illustrations d'origine chinoise, faisons un bref détour en Europe, grâce à des extraits d'articles qui présentent les arts de : la peinture sous verre, de la peinture éludorique (fixée sous/sur verre), et enfin celui du verre églomisé.

Avant de présenter quelques illustrations d'origine chinoise, faisons un bref détour en Europe, grâce à des extraits d'articles qui présentent les arts de : la peinture sous verre, de la peinture éludorique (fixée sous/sur verre), et enfin celui du verre églomisé.

Grosso modo, la production que je désigne ici sous le titre de ce sujet comme "peinture sous verre", était déclinée selon ces différentes techniques, parfois combinées entre-elles au point qu'il serait trop fastidieux de présenter les nuances et nombreuses sous-techniques.

Il s'agit juste de comprendre le principe général...

La peinture sur verre inversée, ou peinture sous verre

La peinture sur verre inversée, ou peinture sous verre

La peinture sur verre inversé (ou peinture sous verre) est une technique artistique difficile qui s'exécute directement sur une feuille de verre. Le verre supporte la peinture comme le ferait une toile.(...)

Ainsi le verre sert à la fois de support et de vernis protecteur. C'est une technique de peinture « à froid » de sorte que le procédé n'exige pas de cuisson au four.

Le pigment est lié au verre par un véhicule huileux le plus souvent à base de vernis.

Marie Leszczynska, reine de France

Pierre Jouffroy, d’après Jean-Marc Nattier

Gouache sur verre, 1760

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

En peinture sur verre inversé la technique est unique car l'œuvre est réalisée sur le dos du verre. Alors que sur une toile on esquisse la composition à grands traits pour ensuite exécuter les aplats de couleur pour terminer graduellement par les détails, en peinture sur verre inversé on procède à l'inverse.

C'est donc dire que l'artiste peintre sur verre commence par les finesses de l'œuvre pour terminer avec les fonds.

Ainsi jusqu'au moindre détail, le peintre doit imaginer dès le départ la version définitive de l'image à réaliser sachant bien qu'il devra aussi composer avec un « effet miroir » lors de l'exécution de l'image puisque ce qui est peint à l'envers à droite se trouve à l'endroit à gauche.

Susanna im Bade und die beiden Alten

Johann Peter Abesch

Hinterglasmalerei, um 1720

Image : Vitrocentre Romont (Foto: Yves Eigenmann, Fribourg)

La peinture sur verre a pour avantage d'offrir une bonne protection à la peinture mais elle demande une grande maîtrise technique car la couche peinte en premier sera la première couche visible.

La vitre protège la peinture et lui donne son aspect lisse et brillant caractéristique. (...)

Histoire :

La peinture sur verre inversé est connue en Occident depuis l'Antiquité. Qualifiée d'« art savant », c'est au cours de la Renaissance que cette forme d'art atteignit son apogée en ce que les compositions devinrent très élaborées, les coloris harmonieux, la virtuosité de la technique étourdissante.

Jusque-là réservée à une élite d'artistes, la peinture sur verre inversé s'est largement diffusée et deviendra un art populaire en Europe lors de la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle. (…)

Marie-Antoinette

Anonyme, XIXe siècle

Gouache fixée sous verre

RMN-Grand Palais (MuCEM) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Incroyable

Peinture sous verre

Fin XVIIIe, début XIXe siècle

Musée Borély Marseille

Image : Wikipedia

Regency Reverse-Glass Painted Silhouette Group

By Charles Rosenberg (1745-1844), circa 1800

Depicting, from left to right: Sir William Fawcet or Master General; Frederick, Duke of York; the Duke of Wirtemburg; George III and Queen Charlotte; the Stadholder; and George IV when Prince of Wales, beneath trees, in a moulded giltwood frame (…)

Image : Christie’s

* Source et article dans son intégralité, à lire ici : Wikipédia - La peinture sur verre inversée

La peinture éludorique ou fixé sous (ou sur) verre

La peinture éludorique ou fixé sous (ou sur) verre

La peinture éludorique un procédé qui consiste à peindre un sujet sur un tissu très fin ou sur une plaque de verre.

Au lieu d'appliquer un vernis protecteur sur la peinture, l'artiste colle directement un verre de protection sur la couche picturale. Il obtient ainsi une grande intensité de couleurs et une surface parfaitement brillante.

La technique est inventée par Armant Vincent de Montpetit (1713-1800) durant la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle.

Louis XV, roi de France

Armand-Vincent de Montpetit

Huile sur toile collée au revers d'une glace selon la technique de la peinture éludorique

1774

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Jean Popovitch

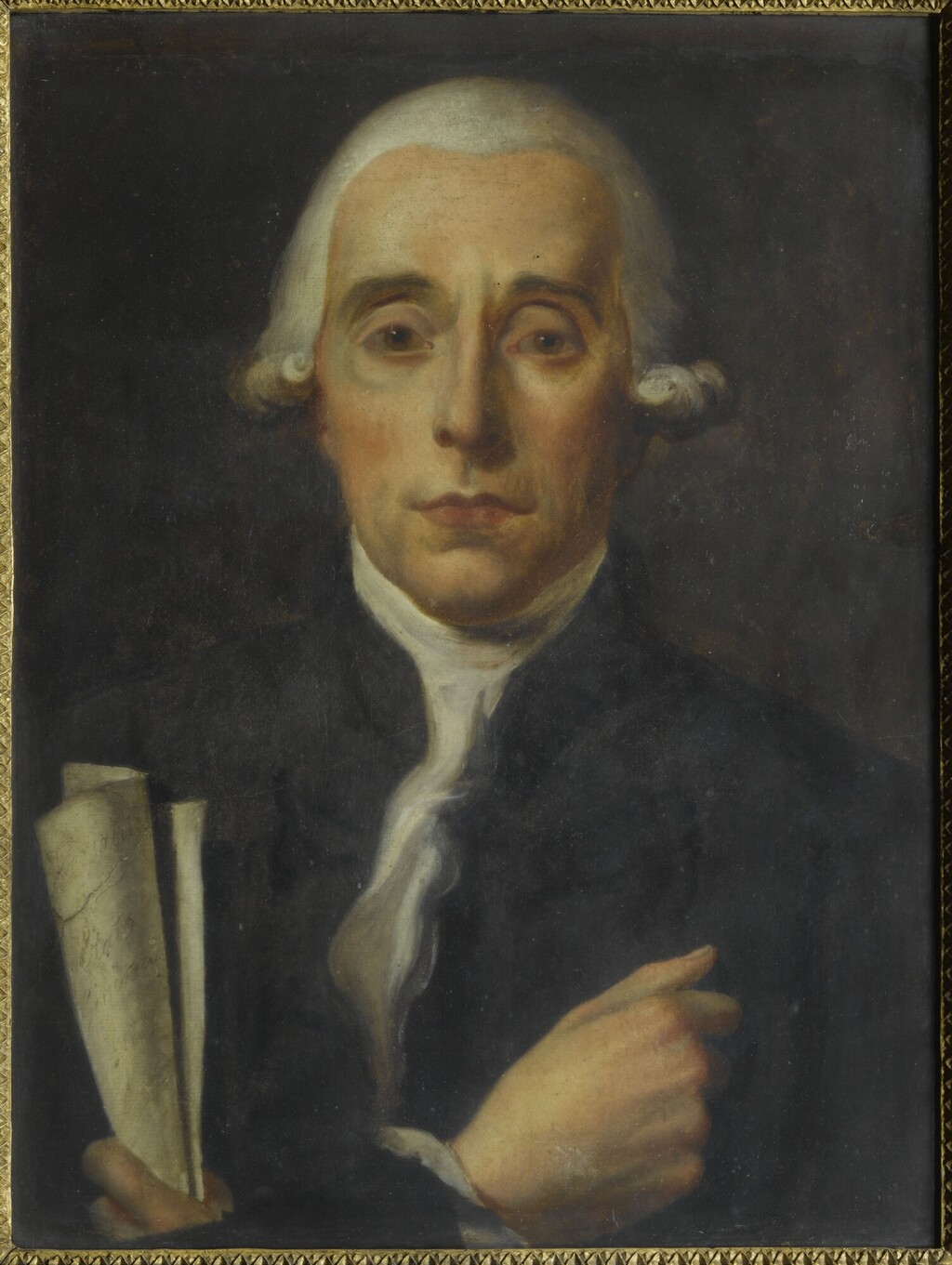

Jean-Sylvain Bailly

Anonyme, d'après Jacques-Louis David

Huile sur papier collé sur une plaque de verre

XVIIIe siècle

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Franck Raux

Après avoir été appliquée sur des grands formats (vu la fragilité du verre à cette époque, avec un succès douteux), cette technique est restée fréquente jusqu'au milieu du XIXe siècle pour des miniatures destinées à orner des boîtes et des presse-papiers.

Avec le temps, il arrive que le support se décolle du verre.

Certains artistes peignent directement sur la plaque de verre, puis protègent leur œuvre avec un carton.

* Source et article dans son intégralité, à lire ici : Wikipédia - La peinture éludorique

La technique du verre églomisé

La technique du verre églomisé

La technique du verre églomisé remonte à l'Antiquité.

Elle consiste à fixer une mince feuille d'or ou d'argent sous le verre ; le dessin est exécuté à la pointe sèche et est maintenu par une deuxième couche ou une plaque de verre.

Cependant le procédé est fragile, d'une part parce que le support est le verre et d'autre part parce que l'or a tendance à se déliter avec le temps et en raison de la chaleur, qu'elle vienne du chauffage ou des rayons du soleil.

Bildnis des Pastors Wilhelm Augustus Klepperbein

Jonas Zeuner

Spiegelglas. In Gold- und Silberfolie, schwarz hintermalt.

Um 1780

Image : Vitrocentre Romont (Foto: Yves Eigenmann, Fribourg)

Histoire :

Dans l'Antiquité, les artisans égyptiens savaient déjà souder au feu des feuilles d'or entre deux pellicules de verre.

Lors de la Renaissance, la technique est utilisée dans la décoration des cabinets : des panneaux ornés de rinceaux et d'arabesques sur fond doré habillent les façades des tiroirs.

Dès le XVIIIe siècle, siècle des Lumières, la technique se répand en Europe sur le couvercle de bibelots, de bonbonnières, tabatières et sur des miroirs. Ce procédé était utilisé en Bohême sous le nom de Zwischengoldglasser.

A German Baroque verre églomisé mirror

Lohr, circa 1725-30

Count Lothar Franz von Schönborn established a mirror manufactory in Lohr, Bavaria, in 1698.

Image : Sotheby’s

En France, c'est Jean-Baptiste Glomy (vers 1711-1786), encadreur parisien des rois Louis XV puis Louis XVI, qui remit ce procédé à la mode.

Il l'appliqua au passe-partout des gravures et connut un tel succès, surtout à partir des années 1780, que le verre églomisé perpétua désormais son nom.

Box with portrait of Jean Paul Marat

Verre églomisé, pasteboard

France, late 18th century

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Catherine II (1729–1796), Empress of Russia

Verre églomisé

Russia, second half 18th century

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Au XIXe siècle, divers décorateurs combinèrent cette dorure avec de la gravure et des peintures toujours sous verre. Ils réalisèrent ainsi des ornements destinés à couvrir le plafond, les murs et la devanture des magasins.

De véritables chefs-d'œuvre ont égayé les rues du Paris de la Belle Époque puis de toutes les grandes villes du monde.(...)

Boulangerie, 19 rue Montgallet à Paris

Image : Lionel Allorge / Wikipedia

* Source et article dans son intégralité à lire, ici : Wikipedia - Verre églomisé

A suivre, quelques chinoiseries du XVIIIe siècle, destinées au marché européen...

Présentation :

Reflets de Chine - Trois siècles de peinture sous verre chinoise

16 juin 2019 - 1er mars 2020

Paysages fantastiques, portraits d’enfants et de concubines, scènes tirées de la vie familiale et de grands romans épiques, créatures issues de la mythologie, représentations de symboles : le Vitromusée propose la première grande exposition présentant un panorama de la peinture sous verre chinoise, une production artistique exceptionnelle et peu connue à ce jour.

La bonne bergère, vers 1760

Image : Collection Vitrocentre

A travers un choix exclusif d’environ 130 œuvres provenant de deux collections privées majeures d’Allemagne et de France ainsi que de celle du Vitromusée, complétées par quelques prêts d’autres musées suisses, l’exposition retrace la longue histoire de la peinture sous verre chinoise : sa naissance au XVIIIe siècle, issue de la rencontre des traditions picturales chinoise et occidentale, sa « mondialisation » via l’exportation, avant de devenir un art populaire au XIXe siècle.

Elle témoigne du goût de la cour impériale chinoise de l’époque, de l’engouement de l’aristocratie et de la bourgeoisie européenne, puis américaine pour les chinoiseries et donne une idée de la vie du peuple chinois, en dehors des classes privilégiées.

Plongé dans un monde exotique, le visiteur découvre un domaine fascinant du patrimoine culturel chinois, et des œuvres d’une extrême finesse d’exécution.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Vitromusée de Romont

__________________________

INTRODUCTION TECHNIQUE :

Grosso modo, la production que je désigne ici sous le titre de ce sujet comme "peinture sous verre", était déclinée selon ces différentes techniques, parfois combinées entre-elles au point qu'il serait trop fastidieux de présenter les nuances et nombreuses sous-techniques.

Il s'agit juste de comprendre le principe général...

La peinture sur verre inversé (ou peinture sous verre) est une technique artistique difficile qui s'exécute directement sur une feuille de verre. Le verre supporte la peinture comme le ferait une toile.(...)

Ainsi le verre sert à la fois de support et de vernis protecteur. C'est une technique de peinture « à froid » de sorte que le procédé n'exige pas de cuisson au four.

Le pigment est lié au verre par un véhicule huileux le plus souvent à base de vernis.

Marie Leszczynska, reine de France

Pierre Jouffroy, d’après Jean-Marc Nattier

Gouache sur verre, 1760

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

En peinture sur verre inversé la technique est unique car l'œuvre est réalisée sur le dos du verre. Alors que sur une toile on esquisse la composition à grands traits pour ensuite exécuter les aplats de couleur pour terminer graduellement par les détails, en peinture sur verre inversé on procède à l'inverse.

C'est donc dire que l'artiste peintre sur verre commence par les finesses de l'œuvre pour terminer avec les fonds.

Ainsi jusqu'au moindre détail, le peintre doit imaginer dès le départ la version définitive de l'image à réaliser sachant bien qu'il devra aussi composer avec un « effet miroir » lors de l'exécution de l'image puisque ce qui est peint à l'envers à droite se trouve à l'endroit à gauche.

Susanna im Bade und die beiden Alten

Johann Peter Abesch

Hinterglasmalerei, um 1720

Image : Vitrocentre Romont (Foto: Yves Eigenmann, Fribourg)

La peinture sur verre a pour avantage d'offrir une bonne protection à la peinture mais elle demande une grande maîtrise technique car la couche peinte en premier sera la première couche visible.

La vitre protège la peinture et lui donne son aspect lisse et brillant caractéristique. (...)

Histoire :

La peinture sur verre inversé est connue en Occident depuis l'Antiquité. Qualifiée d'« art savant », c'est au cours de la Renaissance que cette forme d'art atteignit son apogée en ce que les compositions devinrent très élaborées, les coloris harmonieux, la virtuosité de la technique étourdissante.

Jusque-là réservée à une élite d'artistes, la peinture sur verre inversé s'est largement diffusée et deviendra un art populaire en Europe lors de la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle. (…)

Marie-Antoinette

Anonyme, XIXe siècle

Gouache fixée sous verre

RMN-Grand Palais (MuCEM) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Incroyable

Peinture sous verre

Fin XVIIIe, début XIXe siècle

Musée Borély Marseille

Image : Wikipedia

Regency Reverse-Glass Painted Silhouette Group

By Charles Rosenberg (1745-1844), circa 1800

Depicting, from left to right: Sir William Fawcet or Master General; Frederick, Duke of York; the Duke of Wirtemburg; George III and Queen Charlotte; the Stadholder; and George IV when Prince of Wales, beneath trees, in a moulded giltwood frame (…)

Image : Christie’s

* Source et article dans son intégralité, à lire ici : Wikipédia - La peinture sur verre inversée

La peinture éludorique un procédé qui consiste à peindre un sujet sur un tissu très fin ou sur une plaque de verre.

Au lieu d'appliquer un vernis protecteur sur la peinture, l'artiste colle directement un verre de protection sur la couche picturale. Il obtient ainsi une grande intensité de couleurs et une surface parfaitement brillante.

La technique est inventée par Armant Vincent de Montpetit (1713-1800) durant la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle.

Louis XV, roi de France

Armand-Vincent de Montpetit

Huile sur toile collée au revers d'une glace selon la technique de la peinture éludorique

1774

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Jean Popovitch

Jean-Sylvain Bailly

Anonyme, d'après Jacques-Louis David

Huile sur papier collé sur une plaque de verre

XVIIIe siècle

Image : RMN-GP (Château de Versailles) / Franck Raux

Après avoir été appliquée sur des grands formats (vu la fragilité du verre à cette époque, avec un succès douteux), cette technique est restée fréquente jusqu'au milieu du XIXe siècle pour des miniatures destinées à orner des boîtes et des presse-papiers.

Avec le temps, il arrive que le support se décolle du verre.

Certains artistes peignent directement sur la plaque de verre, puis protègent leur œuvre avec un carton.

* Source et article dans son intégralité, à lire ici : Wikipédia - La peinture éludorique

La technique du verre églomisé remonte à l'Antiquité.

Elle consiste à fixer une mince feuille d'or ou d'argent sous le verre ; le dessin est exécuté à la pointe sèche et est maintenu par une deuxième couche ou une plaque de verre.

Cependant le procédé est fragile, d'une part parce que le support est le verre et d'autre part parce que l'or a tendance à se déliter avec le temps et en raison de la chaleur, qu'elle vienne du chauffage ou des rayons du soleil.

Bildnis des Pastors Wilhelm Augustus Klepperbein

Jonas Zeuner

Spiegelglas. In Gold- und Silberfolie, schwarz hintermalt.

Um 1780

Image : Vitrocentre Romont (Foto: Yves Eigenmann, Fribourg)

Histoire :

Dans l'Antiquité, les artisans égyptiens savaient déjà souder au feu des feuilles d'or entre deux pellicules de verre.

Lors de la Renaissance, la technique est utilisée dans la décoration des cabinets : des panneaux ornés de rinceaux et d'arabesques sur fond doré habillent les façades des tiroirs.

Dès le XVIIIe siècle, siècle des Lumières, la technique se répand en Europe sur le couvercle de bibelots, de bonbonnières, tabatières et sur des miroirs. Ce procédé était utilisé en Bohême sous le nom de Zwischengoldglasser.

A German Baroque verre églomisé mirror

Lohr, circa 1725-30

Count Lothar Franz von Schönborn established a mirror manufactory in Lohr, Bavaria, in 1698.

Image : Sotheby’s

En France, c'est Jean-Baptiste Glomy (vers 1711-1786), encadreur parisien des rois Louis XV puis Louis XVI, qui remit ce procédé à la mode.

Il l'appliqua au passe-partout des gravures et connut un tel succès, surtout à partir des années 1780, que le verre églomisé perpétua désormais son nom.

Box with portrait of Jean Paul Marat

Verre églomisé, pasteboard

France, late 18th century

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Catherine II (1729–1796), Empress of Russia

Verre églomisé

Russia, second half 18th century

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Au XIXe siècle, divers décorateurs combinèrent cette dorure avec de la gravure et des peintures toujours sous verre. Ils réalisèrent ainsi des ornements destinés à couvrir le plafond, les murs et la devanture des magasins.

De véritables chefs-d'œuvre ont égayé les rues du Paris de la Belle Époque puis de toutes les grandes villes du monde.(...)

Boulangerie, 19 rue Montgallet à Paris

Image : Lionel Allorge / Wikipedia

* Source et article dans son intégralité à lire, ici : Wikipedia - Verre églomisé

___________________

A suivre, quelques chinoiseries du XVIIIe siècle, destinées au marché européen...

Dernière édition par La nuit, la neige le Mar 24 Mai 2022, 10:28, édité 2 fois

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Encore un beau sujet, truffé d'explications techniques passionnantes ! Merci !!!

La nuit, la neige a écrit:En peinture sur verre inversé la technique est unique car l'œuvre est réalisée sur le dos du verre. Alors que sur une toile on esquisse la composition à grands traits pour ensuite exécuter les aplats de couleur pour terminer graduellement par les détails, en peinture sur verre inversé on procède à l'inverse.

C'est donc dire que l'artiste peintre sur verre commence par les finesses de l'œuvre pour terminer avec les fonds.

Ainsi jusqu'au moindre détail, le peintre doit imaginer dès le départ la version définitive de l'image à réaliser sachant bien qu'il devra aussi composer avec un « effet miroir » lors de l'exécution de l'image puisque ce qui est peint à l'envers à droite se trouve à l'endroit à gauche.

... épatant !!!

remarquable !!!

remarquable !!!

Cette peinture ne souffre pas le plus petit coup de pinceau malencontreux .

Quant à la technique du verre églomisé, nous l'avons déjà évoquée et expliquée au sujet de cette bague qu'Esterhazy fait tenir à Fersen de la part de Marie-Antoinette. Réversible, elle présente trois fleurs de lys sur une face et la devise "Lâche qui les abandonne" sur l'autre .

C'est ici :

https://marie-antoinette.forumactif.org/t3013-historiae-secrets-et-la-bague-dite-de-fersen?highlight=FERSEN

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Quelques "chinoiseries" !

Pour rappel, et en ce qui concerne en tous cas ce type de production, ces créations étaient exclusivement destinées aux marchés européens, amateurs de ce genre d'objets "exotiques".

Matériaux de base et techniques furent importés en Chine, où les artisans locaux réalisèrent ces "peintures" destinées à être exportées en Europe. Une fois arrivées dans le pays de destination, les oeuvres étaient agrémentées de bronze ou, plus précisément en ce qui concerne ce sujet, de cadre en bois doré dans le goût du temps.

Commençons par un exemple élaboré selon la technique du verre églomisé (décrite ci-dessus), assez rare...

Commençons par un exemple élaboré selon la technique du verre églomisé (décrite ci-dessus), assez rare...

A rare pair of verre églomisé vermillion and gilt decorated wall appliques

Early 18th century

decorated with chinoiserie scenes, with brass candle-arms

77cm. high; 2ft. 6¼in.

Photo : Sotheby's

Photo : Sotheby's

Catalogue note :

These wall sconces feature the process for reverse-decorating glass with metal foil and paint which is thought to have derived its name from a French framer Jean-Baptiste Glomy (d. 1786) who rediscovered the technique in the late 18th century.

Although verre églomisé is typically associated with the borders of late 17th/early 18th century mirrors, this method of decoration was practised during the high renaissance (...)

Whilst the verre églomisé borders found on mirrors contemporary to the present lot are characterised by Berainesque influenced designs, the decoration here is more typical of the Chinoiserie motifs applied to English and continental japanned cabinets of the same period.

One of the principal design sources for japanning was John Stalker and George Parker's Treatise of Japanning, Varnishing and Guilding published in 1688 and the decoration on the appliqués here appear to be a rare example of the verre églomisé technique expressed in this style.

Plus communes, ces autres oeuvres furent réalisées selon le même principe de "grattage et découpage" de la fine couche composant la surface arrière d'un miroir, permettant par la suite de peindre sous verre les décors et motifs choisis...

Plus communes, ces autres oeuvres furent réalisées selon le même principe de "grattage et découpage" de la fine couche composant la surface arrière d'un miroir, permettant par la suite de peindre sous verre les décors et motifs choisis...

Note au catalogue :

Although glass was widely used in ancient China, the technique of producing flat glass in China was not accomplished until the 19th Century. Even in the imperial glass workshops, set up Peking (Beijing) in 1696 under the supervision of the Jesuit Kilian Stumpf, window glass or mirrored glass was not successfully produced.

As a result, from the middle of the 18th century onwards, when reverse glass painting was already popular in Europe, sheets of both clear and mirrored glass were sent to Canton from Europe.

The practice of painting on mirrors developed in China after 1715 when the Jesuit missionary Father Castiglione arrived in Peking. He found favor with the Emperors Yang Cheng and Ch’ien Lung and was entrusted with the decoration of the Imperial Garden in Peking.

He learned to paint in oil on glass, a technique that was already practiced in Europe but which was unknown in China in the 17th century.

Chinese artists, who were already expert in painting and calligraphy, took up the practice of painting in oil on glass, tracing the outlines of their designs on the back of the mirror plate and, using a special steel implement, scraped away the mirror backing to reveal the glass that could then be painted.

The glass paintings were purely made for export, and initially depicted bucolic landscapes, frequently with Chinese figures at various leisurely pursuits.

The demand for such paintings was fueled by the mania in Europe for all things Chinese, and they were commonly placed in elaborate Chippendale or chinoiserie frames.

A Pair of Chinese Export Reverse Painted Mirrors

18th Century

Each of a river landscape, the foreground of one with a man and lady holding picked flowers with a sheep and lamb, the other with another couple admiring a painting album with a dog and a golden pheasant, in their original pierce carved giltwood Chippendale frames

overall 32" x 22.5" — 81.3 x 57.2 cm.

Image : Waddington’s Asian Art department

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

The popularity of European aesthetic and artistic techniques in the Chinese Imperial court was mirrored by the emergence of ‘Chinoiserie’ tastes in West. Glass and mirror paintings became a product of the two trends, where plates were painted with idyllic and exoticized scenes of the Far East using European painting techniques.

The operation was arduous; mirror plates were sent from Europe over to Chinese workshops, where they would strip sections of mercury and carefully paint designs on the reverse.

Once complete, the plates would be laboriously transported back to the West, further adding to their rarity and value.

Photo : Christie's

A chinese export reverse-glass mirror painting

Circa 1760

The rectangular plate depicting an elegant lady seated beneath a tree attended by a musician playing a flute and another standing figure with a basket of flowers, with a spaniel, deer and cock and hen golden pheasants at their feet and with distant buildings and mountains,

in a George III carved giltwood frame

35 x 37 in. (89 x 94 in.)

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

The technique for creating pictures on imported miror glass is thought to have been promoted by Father Guiseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) who reached Peking in 1715 and found favour with the Imperial rulers.

The process had already been used in Europe, a process termed verre églomisé, and Chinese artists adopted the method though Alvarez Semedo, a Portuguese living in China wrote that they had no knowlege of painting in oils and have 'more curiosities than perfection'.

The finished articles however were widely admired in European markets, and when sent back to Europe, enduring another hazardous sea voyage, they were quickly adopted along with Chinese porcelain, wallpaper, silks and lacquer in the most fashionable circles desirous of the exotic.

Miroir en verre églomisé à décor de chinoiseries

Fin du XVIIIe siècle

Peint en polychromie, représentant une scène de cour avec personnages ;

encadrement en bois doré Haut. avec cadre 82 cm, larg. 55,5 cm

Photo : Sotheby's

A Chinese-export Reverse Mirror Painting

Late 18th century

The bevelled plate depicting two pairs of pheasants on rocky outcrops among flowering plants, in a modern pierced giltwood frame with acanthus clasps

46½ x 31 in. (118 x 79 cm.)

Paire de miroirs en verre églomisé

Travail chinois réalisé pour le marché occidental, fin du XVIIIe siècle

Chaque miroir représentant une femme en costume traditionnel, avec des draperies et vases fleuris à l'arrière plan ; dans des cadres en bois doré de goût rocaille

Haut. 76 cm, larg. 38 cm

Photo : Sotheby's

A Chinese reverse-glass mirror painting

The mirror 18th century, the frame 19th century

The mirror painted with birds, one hanging from a branch, a hawk clutching a small bird in its claw, among flowering peonies and prunus branches, in a shaped giltwood frame, label to the rear 'John Sparks ltd, 128, Mount Street, W'

27 ¼ in. (69 cm.) high; 20 ¾ in. (53 cm.) wide

A pair of Chinese-export reverse mirror paintings

Qing Dynasty, Third quarter 18th Century

Each depicting figures in river landscapes with buildings beyond, within a George II-style giltwood frame,

one inscribed to the reverse '2' within a circle, the other inscribed to the reverse 'ODELL [?] '

27 in. (68.5 cm.) high, 33 in. (84 cm.) wide, each

Photo : Christie's

A George III Giltwood Overmantel Mirror with Chinese Export Mirror Paintings

Circa 1765

With pierced foliate cresting over a divided frame carved with scrolling foliage, leafy branches and a pair of ho-ho birds, with variously shaped plates, the upper central plate with a painting depicting a lady and her attendants within a river landscape, flanked by outer plates depicting still lives and large scale birds, restorations to the birds' heads and to the cresting, re-gilt

74¼ in. (188.5 cm.) high; 68 in. (173 cm.) wide

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

This exceptional mirror or 'chymney glass' is an accomplished amalgam of Chinese, rococo and classical design. Likely to have been supplied for a fashionable Chinese-style bedroom, the frame is beautifully conceived with deep fluid carving that effectively showcases the Chinese mirror paintings within.

The frame was undoubtedly made by one of London’s pre-eminent cabinet-makers such as Thomas Chippendale, John Linnell or the partnership of Samuel Norman and James Whittle. The mirror paintings were probably the patron's own (...).

Both the practice of painting on glass and the flat glass itself were introduced to China in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. China had a long history of producing utensils and decorative objects in glass. The glass workshop in the Forbidden city was established in 1696, but no flat glass was produced and when it was attempted it was reported that the manufacturers ‘do not know how to do manufacture it with the proper materials’ (Breton de la Martinière, China, its costume, art etc, translated 1813). However, visiting dignitaries had brought mirrors as gifts for the Emperor, such as a Dutch mission which in 1686 presented the Emperor K’ang-Hsi with a pair of large European mirrors, the quality of which was a revelation to the Chinese.

The practice of painting on mirrors developed in China after 1715 when the Jesuit missionary Father Castiglione arrived in Peking. He found favour with the Emperors Yang Cheng and Ch’ien Lung and was entrusted with the decoration of the Imperial Garden in Peking. He learnt to paint in oil on glass, a technique that was already practiced in Europe but which was unknown in China in the 17th century. Chinese artists, who were already expert in painting and calligraphy, took up the practice, tracing the outlines of their designs on the back of the mirror plate and, using a special steel implement, scraping away the mirror backing to reveal the glass that could then be painted. Common designs included still lives, birds and groups of figures, usually depicted against backgrounds of rivers or pavilions.

Many mirrors were brought back to Europe by the companies who routinely plied their trade in the far East, with some carried as ‘private trade’ by crew members (...).

The demand for such painting was fuelled by the mania in Europe for Chinese fashions, promoted by the likes of Sir William Chambers, whose Designs for Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines and Utensils was issued in 1757, and which found expression in homes of the fashionable cognoscenti. Frederick, Prince of Wales (d. 1752) decorated his gallery in the state apartments with 'four large painted looking glasses from china' for the window-piers according to a description of William Kent’s work at Kew (Sir William Chambers' Plans, Elevations, etc. of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew, 1763, p. 2), while the Chinese Bedroom at Badminton House, Gloucestershire was fitted up for the 4th Duke of Beaufort by William Linnell in 1752-54.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's

Rare pair of China Trade Reverse Glass Painted Mirror Pictures.

Made in Canton and Exported Exclusively for the English Upper Class.

Last Quarter of the 18th Century .

As is quite normal the finely carved wooden frames have been made in England at a later date to suit the individual taste of the purchasing client.

Image : Michael Lipitch - Fine Antique Furniture & Objects

A George III Giltwood Frame with a Chinese Mirror Painting

The frame: English, circa 1780

The mirror painting: Chinese, Qianlong, circa 1765

Height: 43 in; 109.5 cm - Width: 37 in; 94 cm

Image : Ronald Phillips - Fine Antique English Furniture

Je pense que vous avez compris le principe !

A suivre...

Pour rappel, et en ce qui concerne en tous cas ce type de production, ces créations étaient exclusivement destinées aux marchés européens, amateurs de ce genre d'objets "exotiques".

Matériaux de base et techniques furent importés en Chine, où les artisans locaux réalisèrent ces "peintures" destinées à être exportées en Europe. Une fois arrivées dans le pays de destination, les oeuvres étaient agrémentées de bronze ou, plus précisément en ce qui concerne ce sujet, de cadre en bois doré dans le goût du temps.

A rare pair of verre églomisé vermillion and gilt decorated wall appliques

Early 18th century

decorated with chinoiserie scenes, with brass candle-arms

77cm. high; 2ft. 6¼in.

Photo : Sotheby's

Photo : Sotheby's

Catalogue note :

These wall sconces feature the process for reverse-decorating glass with metal foil and paint which is thought to have derived its name from a French framer Jean-Baptiste Glomy (d. 1786) who rediscovered the technique in the late 18th century.

Although verre églomisé is typically associated with the borders of late 17th/early 18th century mirrors, this method of decoration was practised during the high renaissance (...)

Whilst the verre églomisé borders found on mirrors contemporary to the present lot are characterised by Berainesque influenced designs, the decoration here is more typical of the Chinoiserie motifs applied to English and continental japanned cabinets of the same period.

One of the principal design sources for japanning was John Stalker and George Parker's Treatise of Japanning, Varnishing and Guilding published in 1688 and the decoration on the appliqués here appear to be a rare example of the verre églomisé technique expressed in this style.

Note au catalogue :

Although glass was widely used in ancient China, the technique of producing flat glass in China was not accomplished until the 19th Century. Even in the imperial glass workshops, set up Peking (Beijing) in 1696 under the supervision of the Jesuit Kilian Stumpf, window glass or mirrored glass was not successfully produced.

As a result, from the middle of the 18th century onwards, when reverse glass painting was already popular in Europe, sheets of both clear and mirrored glass were sent to Canton from Europe.

The practice of painting on mirrors developed in China after 1715 when the Jesuit missionary Father Castiglione arrived in Peking. He found favor with the Emperors Yang Cheng and Ch’ien Lung and was entrusted with the decoration of the Imperial Garden in Peking.

He learned to paint in oil on glass, a technique that was already practiced in Europe but which was unknown in China in the 17th century.

Chinese artists, who were already expert in painting and calligraphy, took up the practice of painting in oil on glass, tracing the outlines of their designs on the back of the mirror plate and, using a special steel implement, scraped away the mirror backing to reveal the glass that could then be painted.

The glass paintings were purely made for export, and initially depicted bucolic landscapes, frequently with Chinese figures at various leisurely pursuits.

The demand for such paintings was fueled by the mania in Europe for all things Chinese, and they were commonly placed in elaborate Chippendale or chinoiserie frames.

A Pair of Chinese Export Reverse Painted Mirrors

18th Century

Each of a river landscape, the foreground of one with a man and lady holding picked flowers with a sheep and lamb, the other with another couple admiring a painting album with a dog and a golden pheasant, in their original pierce carved giltwood Chippendale frames

overall 32" x 22.5" — 81.3 x 57.2 cm.

Image : Waddington’s Asian Art department

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

The popularity of European aesthetic and artistic techniques in the Chinese Imperial court was mirrored by the emergence of ‘Chinoiserie’ tastes in West. Glass and mirror paintings became a product of the two trends, where plates were painted with idyllic and exoticized scenes of the Far East using European painting techniques.

The operation was arduous; mirror plates were sent from Europe over to Chinese workshops, where they would strip sections of mercury and carefully paint designs on the reverse.

Once complete, the plates would be laboriously transported back to the West, further adding to their rarity and value.

Photo : Christie's

A chinese export reverse-glass mirror painting

Circa 1760

The rectangular plate depicting an elegant lady seated beneath a tree attended by a musician playing a flute and another standing figure with a basket of flowers, with a spaniel, deer and cock and hen golden pheasants at their feet and with distant buildings and mountains,

in a George III carved giltwood frame

35 x 37 in. (89 x 94 in.)

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

The technique for creating pictures on imported miror glass is thought to have been promoted by Father Guiseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) who reached Peking in 1715 and found favour with the Imperial rulers.

The process had already been used in Europe, a process termed verre églomisé, and Chinese artists adopted the method though Alvarez Semedo, a Portuguese living in China wrote that they had no knowlege of painting in oils and have 'more curiosities than perfection'.

The finished articles however were widely admired in European markets, and when sent back to Europe, enduring another hazardous sea voyage, they were quickly adopted along with Chinese porcelain, wallpaper, silks and lacquer in the most fashionable circles desirous of the exotic.

Miroir en verre églomisé à décor de chinoiseries

Fin du XVIIIe siècle

Peint en polychromie, représentant une scène de cour avec personnages ;

encadrement en bois doré Haut. avec cadre 82 cm, larg. 55,5 cm

Photo : Sotheby's

A Chinese-export Reverse Mirror Painting

Late 18th century

The bevelled plate depicting two pairs of pheasants on rocky outcrops among flowering plants, in a modern pierced giltwood frame with acanthus clasps

46½ x 31 in. (118 x 79 cm.)

Paire de miroirs en verre églomisé

Travail chinois réalisé pour le marché occidental, fin du XVIIIe siècle

Chaque miroir représentant une femme en costume traditionnel, avec des draperies et vases fleuris à l'arrière plan ; dans des cadres en bois doré de goût rocaille

Haut. 76 cm, larg. 38 cm

Photo : Sotheby's

A Chinese reverse-glass mirror painting

The mirror 18th century, the frame 19th century

The mirror painted with birds, one hanging from a branch, a hawk clutching a small bird in its claw, among flowering peonies and prunus branches, in a shaped giltwood frame, label to the rear 'John Sparks ltd, 128, Mount Street, W'

27 ¼ in. (69 cm.) high; 20 ¾ in. (53 cm.) wide

A pair of Chinese-export reverse mirror paintings

Qing Dynasty, Third quarter 18th Century

Each depicting figures in river landscapes with buildings beyond, within a George II-style giltwood frame,

one inscribed to the reverse '2' within a circle, the other inscribed to the reverse 'ODELL [?] '

27 in. (68.5 cm.) high, 33 in. (84 cm.) wide, each

Photo : Christie's

A George III Giltwood Overmantel Mirror with Chinese Export Mirror Paintings

Circa 1765

With pierced foliate cresting over a divided frame carved with scrolling foliage, leafy branches and a pair of ho-ho birds, with variously shaped plates, the upper central plate with a painting depicting a lady and her attendants within a river landscape, flanked by outer plates depicting still lives and large scale birds, restorations to the birds' heads and to the cresting, re-gilt

74¼ in. (188.5 cm.) high; 68 in. (173 cm.) wide

Note au catalogue (extrait) :

This exceptional mirror or 'chymney glass' is an accomplished amalgam of Chinese, rococo and classical design. Likely to have been supplied for a fashionable Chinese-style bedroom, the frame is beautifully conceived with deep fluid carving that effectively showcases the Chinese mirror paintings within.

The frame was undoubtedly made by one of London’s pre-eminent cabinet-makers such as Thomas Chippendale, John Linnell or the partnership of Samuel Norman and James Whittle. The mirror paintings were probably the patron's own (...).

Both the practice of painting on glass and the flat glass itself were introduced to China in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. China had a long history of producing utensils and decorative objects in glass. The glass workshop in the Forbidden city was established in 1696, but no flat glass was produced and when it was attempted it was reported that the manufacturers ‘do not know how to do manufacture it with the proper materials’ (Breton de la Martinière, China, its costume, art etc, translated 1813). However, visiting dignitaries had brought mirrors as gifts for the Emperor, such as a Dutch mission which in 1686 presented the Emperor K’ang-Hsi with a pair of large European mirrors, the quality of which was a revelation to the Chinese.

The practice of painting on mirrors developed in China after 1715 when the Jesuit missionary Father Castiglione arrived in Peking. He found favour with the Emperors Yang Cheng and Ch’ien Lung and was entrusted with the decoration of the Imperial Garden in Peking. He learnt to paint in oil on glass, a technique that was already practiced in Europe but which was unknown in China in the 17th century. Chinese artists, who were already expert in painting and calligraphy, took up the practice, tracing the outlines of their designs on the back of the mirror plate and, using a special steel implement, scraping away the mirror backing to reveal the glass that could then be painted. Common designs included still lives, birds and groups of figures, usually depicted against backgrounds of rivers or pavilions.

Many mirrors were brought back to Europe by the companies who routinely plied their trade in the far East, with some carried as ‘private trade’ by crew members (...).

The demand for such painting was fuelled by the mania in Europe for Chinese fashions, promoted by the likes of Sir William Chambers, whose Designs for Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines and Utensils was issued in 1757, and which found expression in homes of the fashionable cognoscenti. Frederick, Prince of Wales (d. 1752) decorated his gallery in the state apartments with 'four large painted looking glasses from china' for the window-piers according to a description of William Kent’s work at Kew (Sir William Chambers' Plans, Elevations, etc. of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew, 1763, p. 2), while the Chinese Bedroom at Badminton House, Gloucestershire was fitted up for the 4th Duke of Beaufort by William Linnell in 1752-54.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's

Rare pair of China Trade Reverse Glass Painted Mirror Pictures.

Made in Canton and Exported Exclusively for the English Upper Class.

Last Quarter of the 18th Century .

As is quite normal the finely carved wooden frames have been made in England at a later date to suit the individual taste of the purchasing client.

Image : Michael Lipitch - Fine Antique Furniture & Objects

A George III Giltwood Frame with a Chinese Mirror Painting

The frame: English, circa 1780

The mirror painting: Chinese, Qianlong, circa 1765

Height: 43 in; 109.5 cm - Width: 37 in; 94 cm

Image : Ronald Phillips - Fine Antique English Furniture

Je pense que vous avez compris le principe !

A suivre...

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Je n'ai pas encore présenté de "chinoiseries" reprenant les codes picturaux des oeuvres occidentales, car ce n'est pas ce que je préfère.

Mais les artistes chinois n'hésitaient pas à reproduire les styles picturaux européens afin de réaliser des oeuvres dédiées à ce marché, et ainsi moins "exotiques".

Business first, il y en avait donc pour tous les goûts...

Voici donc quelques exemples, cette fois-ci réalisés selon la technique de peinture directement "sous/sur verre" (voir explication dans mon message d'introduction), c'est à dire sans les miroirs "grattés" de type verre églomisé.

Voici donc quelques exemples, cette fois-ci réalisés selon la technique de peinture directement "sous/sur verre" (voir explication dans mon message d'introduction), c'est à dire sans les miroirs "grattés" de type verre églomisé.

A pair of Chinese export reverse-painted glass pictures

Late 18th Century

One depicting Anne Lady Lascelles (wife of Edward Lascelles, later 1st Earl of Harewood) in a landscape, the other depicting her daughter, Frances Lascelles with her dog, each in contemporary giltwood frames

24¼ x 18½ in. (62.2 x 47 cm.)

Catalogue Note (extraits) :

This fine pair of late 18th century portraits depict Anne Lady Harewood (1742/3- 1805) and her daughter Lady Francis Douglas, née Lascelles (1762-1817) with her dog. We have been able to identify the sitters for these two portraits with certainty from portraits of both sitters by Francis Cotes (1726-1770) surviving at Harewood House.

In the late 18th century acquiring a portrait of this kind was a novelty preserved for the extremely wealthy. A likeness would need to be created in England to then be exported to China along with the most expensive part of the object at that date, the glass; the likeness would then be copied in reverse to the back of the glass by the Chinese painter then to be returned to England.

By the time the portrait arrived back with the person who commissioned it, the costly, and extremely fragile glass would have completed a treacherous 10,000 mile round-trip, needless to say many such objects did not survive the trip.

The Lascelles family fortune was made from mercantile endeavour, and it would probably be through his contacts in that world that Lord Harewood would order these charming pictures of his wife and daughter.

Miniature Reverse Paintings

Anonymous

China, c. 1775-99

Images : The Corning Museum of Glass

Présentation :

During the reign of the Qing emperor Kangxi (1662–1722), Jesuit missionaries introduced European techniques of glassmaking and apparently of reverse painting on glass in China. Chinese craftsmen excelled to such a degree, that Chinese reverse paintings on glass often are misidentified as being French or English.

According to a contemporary source, most Chinese glass painters worked in Canton, which at the same time was the center of the trade with Europe.

Miniature portraits, often executed in lacquer on copper, were very popular during the late 18th century, and the glass medallions with two European ladies follow this fashion. The portraits are very delicate. They might have been executed after watercolor or pastel portraits, but it is possible they depict ladies who actually stayed in China.

The Foreign Factories (Hongs or Warehouses) of Canton

Anonymous

China, last quarter 18th century

Colorless glass, paint, wood

Image : The Corning Museum of Glass

The waterfront of the Pearl River in 18th-century Canton featured hongs (warehouses owned by foreigners) and dockyards.

The Danish flag on the far left is next to the French pre-Revolutionary flag. The imperial (Austrian), Swedish, British, and Dutch warehouses are shown at the right. Sampans and cargo boats for river trade fill the foreground.

Two Chinese Reverse Mirror Paintings, after Boucher and Eise

Anonymous

China, 18th Century

Oil on glass; gilt frame

Image : Kollenburg Antiquairs via Anticstore

Présentation (extraits) :

Reverse mirror paintings are very difficult to manufacture, because the image has to be applied in an unusual order. The details in the foreground are painted first and the background is added as the last step. Many of these reverse mirror paintings were made after illustrations and engravings of Boucher.

- L’Agréable Leçon

(...) The original is an oval shaped painting of Boucher of 1748 that was presented at the Paris Salon of the same year with exhibit number 19: ‘Un tableau ovale représentant un berger, qui montre à jouer de la flûte a sa bergère’. (an oval scene representing a shepherd who learns his shepherdess to play the flute).

On the Salon of 1750 it was part of item 24: ‘Quatre pastorale de forme ovale […] et la quatrième un berger qui montre à jouer de la flûte à sa bergère sous le même numéro.’(...)

- Le Mouton Favori

(...)The original of this painting by Charles-Dominique Eisen (1720-1778) has disappeared, but a rectangular engraving by R. Gaillard titled ‘Le Mouton Favori’ remained.

An Export Reverse-Glass Painting of Ladies

18th-19th Century

Painted within an oval with a European lady and a younger girl beneath a tall pine tree, with the girl holding up a string of flowers, all reserved on a black ground.

13 ¾ x 11 ¼ in. (34.5 x 28.5 cm.), gilt lacquered frame

Photo : Christie's

A set of four Chinese export oval reverse paintings on glass

Second-half 18th Century, the frames english, circa 1800

Each depicting courting couples, each inscribed on the reverse in pencil, 143, two pictures cracked

12 x 10¼ in. (30.5 x 26 cm.) overall, including frame

Image : Christie's

An Export Reverse Glass Painting of a Court Lady

Qing Dynasty, circa 1785

Oval shape, inspired by an engraving by Henry Moorland, delicately painted with a portrait of a lady with her left arm raised holding a mask, wearing an ornate dress embellished with jewels, her face half shielded by a translucent black veil, glazed with a gilt and lacquered frame

30cm., 11 3/4 in.

Image : Sotheby's

Voilà ! Vous avez compris le principe...

Quitte à faire dans la "chinoiserie", je préfère donc les sujets de "style chinois" à ces autres, "dans le goût" des modèles européens.

A Chinese Export Reverse Glass Painting of an Interior Scene

Qing Dynasty, 19th Century

finely painted with two elegant standing maidens looking at a group of people seated around a table,

contemporary Chinese carved and gilded wood frame

Photo : Sotheby's

A noter que les Etats-Unis ne restèrent pas étrangers à ce commerce...

A noter que les Etats-Unis ne restèrent pas étrangers à ce commerce...

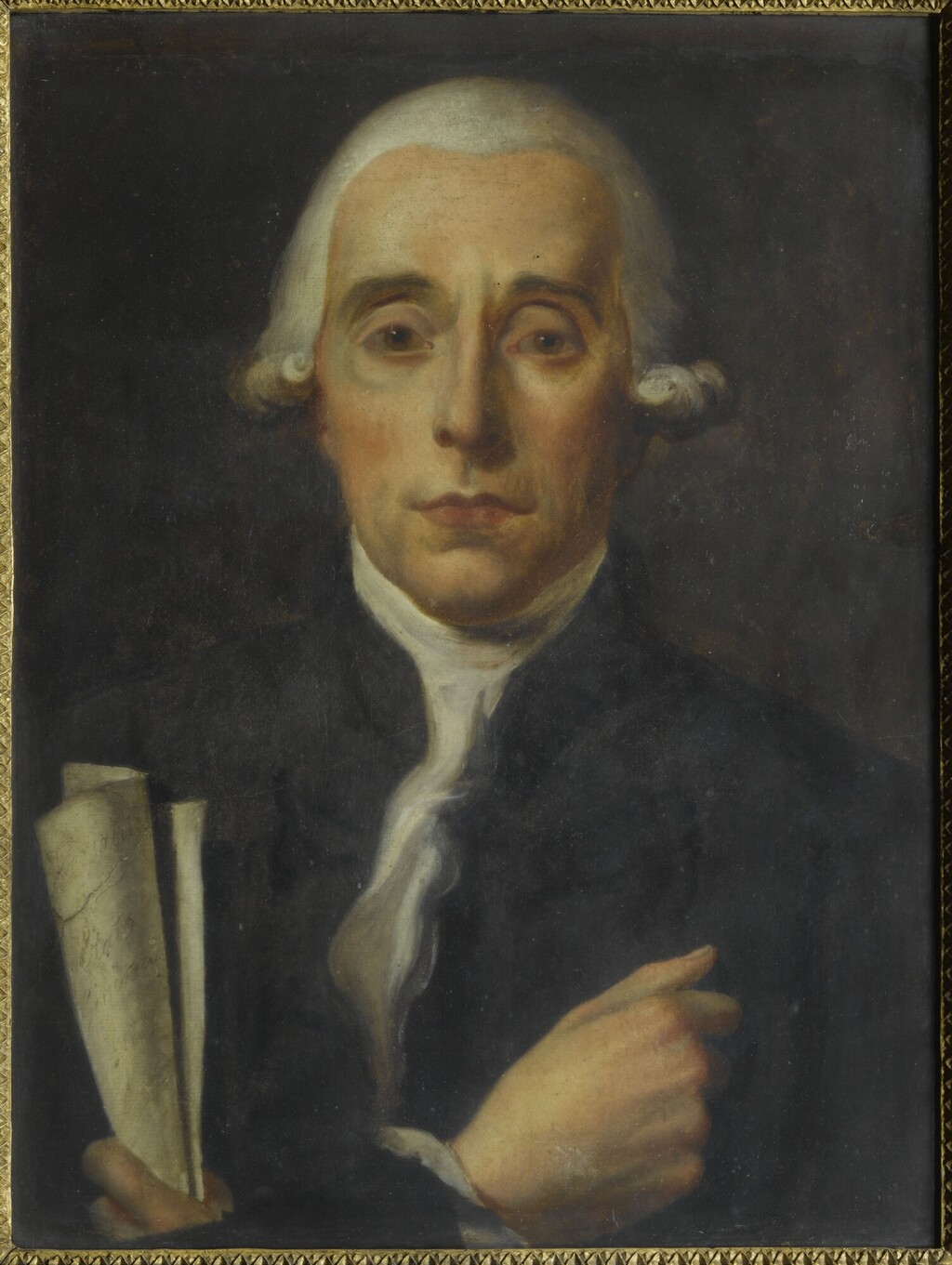

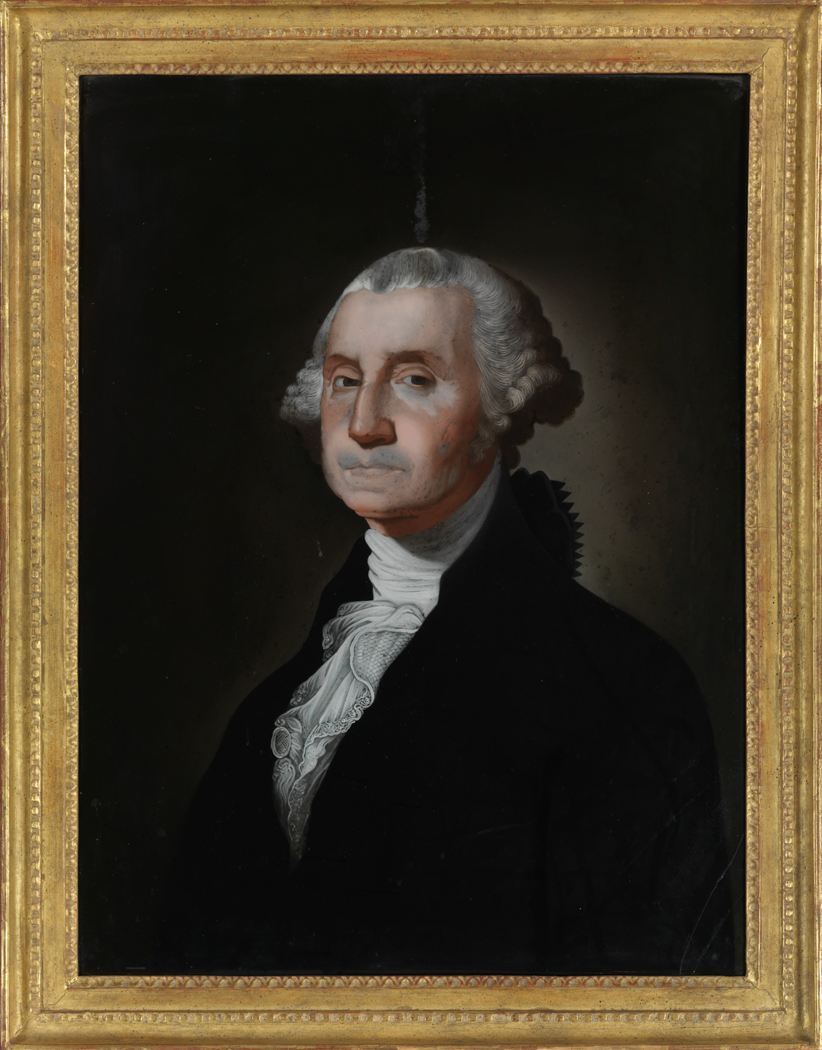

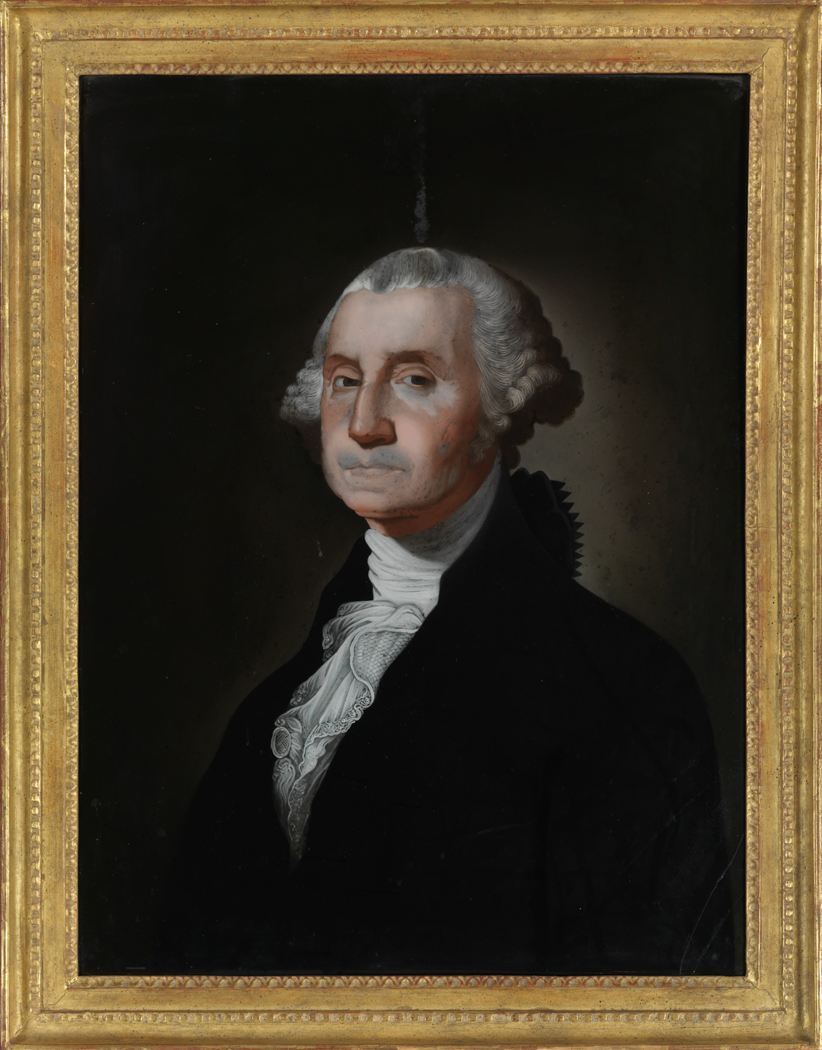

Portrait of George Washington, after a portrait by Gilbert Stuar

Chinese artist, early nineteenth century (1800-1805).

Reverse painting on glass, 32 1/2 x 25 1/2 in. with frame (82.5 x 64.8 cm).

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., gift of Mr. Howell N. White, 1970E78992

Image : Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by the Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo.

America, based on an engraving by Joseph Strutt

Chinese artist, about 1780.

Glass and paint, 17 1/2 x 23 3/8 in. (44.45 x 59.373 cm).

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., museum purchase, 2001; AE85958 Peabody Essex Museum.

Photo : by Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo.

Concernant les liens commerciaux entretenus entre les Etats-Unis et la Chine à partir de l'année 1784, et le commerce de ces "répliques" chinoises selon la technique en vogue de la peinture sous verre, lire cet intéressant article duquel proviennent ces deux illustrations :

Concernant les liens commerciaux entretenus entre les Etats-Unis et la Chine à partir de l'année 1784, et le commerce de ces "répliques" chinoises selon la technique en vogue de la peinture sous verre, lire cet intéressant article duquel proviennent ces deux illustrations :

Washington in China - A Media History of Reverse Painting on Glass

Washington in China - A Media History of Reverse Painting on Glass

Mais les artistes chinois n'hésitaient pas à reproduire les styles picturaux européens afin de réaliser des oeuvres dédiées à ce marché, et ainsi moins "exotiques".

Business first, il y en avait donc pour tous les goûts...

A pair of Chinese export reverse-painted glass pictures

Late 18th Century

One depicting Anne Lady Lascelles (wife of Edward Lascelles, later 1st Earl of Harewood) in a landscape, the other depicting her daughter, Frances Lascelles with her dog, each in contemporary giltwood frames

24¼ x 18½ in. (62.2 x 47 cm.)

Catalogue Note (extraits) :

This fine pair of late 18th century portraits depict Anne Lady Harewood (1742/3- 1805) and her daughter Lady Francis Douglas, née Lascelles (1762-1817) with her dog. We have been able to identify the sitters for these two portraits with certainty from portraits of both sitters by Francis Cotes (1726-1770) surviving at Harewood House.

In the late 18th century acquiring a portrait of this kind was a novelty preserved for the extremely wealthy. A likeness would need to be created in England to then be exported to China along with the most expensive part of the object at that date, the glass; the likeness would then be copied in reverse to the back of the glass by the Chinese painter then to be returned to England.

By the time the portrait arrived back with the person who commissioned it, the costly, and extremely fragile glass would have completed a treacherous 10,000 mile round-trip, needless to say many such objects did not survive the trip.

The Lascelles family fortune was made from mercantile endeavour, and it would probably be through his contacts in that world that Lord Harewood would order these charming pictures of his wife and daughter.

Miniature Reverse Paintings

Anonymous

China, c. 1775-99

Images : The Corning Museum of Glass

Présentation :

During the reign of the Qing emperor Kangxi (1662–1722), Jesuit missionaries introduced European techniques of glassmaking and apparently of reverse painting on glass in China. Chinese craftsmen excelled to such a degree, that Chinese reverse paintings on glass often are misidentified as being French or English.

According to a contemporary source, most Chinese glass painters worked in Canton, which at the same time was the center of the trade with Europe.

Miniature portraits, often executed in lacquer on copper, were very popular during the late 18th century, and the glass medallions with two European ladies follow this fashion. The portraits are very delicate. They might have been executed after watercolor or pastel portraits, but it is possible they depict ladies who actually stayed in China.

The Foreign Factories (Hongs or Warehouses) of Canton

Anonymous

China, last quarter 18th century

Colorless glass, paint, wood

Image : The Corning Museum of Glass

The waterfront of the Pearl River in 18th-century Canton featured hongs (warehouses owned by foreigners) and dockyards.

The Danish flag on the far left is next to the French pre-Revolutionary flag. The imperial (Austrian), Swedish, British, and Dutch warehouses are shown at the right. Sampans and cargo boats for river trade fill the foreground.

Two Chinese Reverse Mirror Paintings, after Boucher and Eise

Anonymous

China, 18th Century

Oil on glass; gilt frame

Image : Kollenburg Antiquairs via Anticstore

Présentation (extraits) :

Reverse mirror paintings are very difficult to manufacture, because the image has to be applied in an unusual order. The details in the foreground are painted first and the background is added as the last step. Many of these reverse mirror paintings were made after illustrations and engravings of Boucher.

- L’Agréable Leçon

(...) The original is an oval shaped painting of Boucher of 1748 that was presented at the Paris Salon of the same year with exhibit number 19: ‘Un tableau ovale représentant un berger, qui montre à jouer de la flûte a sa bergère’. (an oval scene representing a shepherd who learns his shepherdess to play the flute).

On the Salon of 1750 it was part of item 24: ‘Quatre pastorale de forme ovale […] et la quatrième un berger qui montre à jouer de la flûte à sa bergère sous le même numéro.’(...)

- Le Mouton Favori

(...)The original of this painting by Charles-Dominique Eisen (1720-1778) has disappeared, but a rectangular engraving by R. Gaillard titled ‘Le Mouton Favori’ remained.

An Export Reverse-Glass Painting of Ladies

18th-19th Century

Painted within an oval with a European lady and a younger girl beneath a tall pine tree, with the girl holding up a string of flowers, all reserved on a black ground.

13 ¾ x 11 ¼ in. (34.5 x 28.5 cm.), gilt lacquered frame

Photo : Christie's

A set of four Chinese export oval reverse paintings on glass

Second-half 18th Century, the frames english, circa 1800

Each depicting courting couples, each inscribed on the reverse in pencil, 143, two pictures cracked

12 x 10¼ in. (30.5 x 26 cm.) overall, including frame

Image : Christie's

An Export Reverse Glass Painting of a Court Lady

Qing Dynasty, circa 1785

Oval shape, inspired by an engraving by Henry Moorland, delicately painted with a portrait of a lady with her left arm raised holding a mask, wearing an ornate dress embellished with jewels, her face half shielded by a translucent black veil, glazed with a gilt and lacquered frame

30cm., 11 3/4 in.

Image : Sotheby's

Voilà ! Vous avez compris le principe...

Quitte à faire dans la "chinoiserie", je préfère donc les sujets de "style chinois" à ces autres, "dans le goût" des modèles européens.

A Chinese Export Reverse Glass Painting of an Interior Scene

Qing Dynasty, 19th Century

finely painted with two elegant standing maidens looking at a group of people seated around a table,

contemporary Chinese carved and gilded wood frame

Photo : Sotheby's

Portrait of George Washington, after a portrait by Gilbert Stuar

Chinese artist, early nineteenth century (1800-1805).

Reverse painting on glass, 32 1/2 x 25 1/2 in. with frame (82.5 x 64.8 cm).

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., gift of Mr. Howell N. White, 1970E78992

Image : Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by the Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo.

America, based on an engraving by Joseph Strutt

Chinese artist, about 1780.

Glass and paint, 17 1/2 x 23 3/8 in. (44.45 x 59.373 cm).

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., museum purchase, 2001; AE85958 Peabody Essex Museum.

Photo : by Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

en 1989 j'ai transporté en bus deux cadres présentant le roi et la reine jeunes prêtés pour l'exposition à la mairie du V° arrondissement par la BARONNE ELIE, dans un simple grand sac en plastique BHV (j'en tremble encore !!!)

ces deux portraits étaient charmants, mais les personnages avaient les yeux bridé !!!!

MARIE ANTOINETTE

ces deux portraits étaient charmants, mais les personnages avaient les yeux bridé !!!!

MARIE ANTOINETTE

MARIE ANTOINETTE- Messages : 3729

Date d'inscription : 22/12/2013

Age : 78

Localisation : P A R I S

MARIE ANTOINETTE- Messages : 3729

Date d'inscription : 22/12/2013

Age : 78

Localisation : P A R I S

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Présentés prochainement en vente aux enchères, ces exemplaires de peintures sous verre illustrent deux styles appréciés par les acheteurs européens : des compositions " d'inspiration chinoise " et d'autres " à l'européenne ".

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

SECOND HALF 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting a lady holding a feather fan, seated on rocks by a riverside, a boy seated beside her playing a pipe, and a man holding a bird to the left, with a village and mountains beyond, in chalk to the reverse 'S1229 Horlick', in a later japanned frame

21 ¾ in. (55 cm.) high; 29 ½ in. (75 cm.) wide

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

SECOND HALF 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular bevelled plate depicting a lakeside view with a bearded man seated beneath a tree and a lady holding a basket of flowers, with buildings and mountains beyond, in an 18th-century pierced and foliate-carved giltwood frame, altered to fit, re-gilt

32 ¼ in. (82 cm.) high; 46 ¾ in. (119 cm.) wide, including frame

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

LATE 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting a seated woman holding a watch, beneath a floral garland, within a bead-and-reel and ribbon-carved giltwood frame with ribbon-tied cresting

23 ¼ in. (46 cm.) high; 16 in. (34.5 cm.) wide, overall

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-MIRROR PAINTING

LATE 18TH/EARLY 19TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting Clairon and Melpomene, Clairon seated with volumes by Corneille, Racine, Voltaire and Crebillon beside her, Pegasus and a tempietto beyond, in a painted border simulating a frame, with ribbon-tied laurel garland, inscribed 'PROPHETIE ACOMPLIE.', the lower edge inscribed 'J'ai prédit que CLAIRON illustreroit la Scene Et mon espoire n'a pomtété decu: Ella a couronné Melpomene, Melpomene lui rend cequelle en a recu. GARRICK.', enclosed by a border of trailing flowers, in a 19th century giltwood frame

14 in. (35.5 cm.) high; 11 ¾ in. (30 cm.) wide

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's Londres - Vente du 23 juillet 2020

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

SECOND HALF 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting a lady holding a feather fan, seated on rocks by a riverside, a boy seated beside her playing a pipe, and a man holding a bird to the left, with a village and mountains beyond, in chalk to the reverse 'S1229 Horlick', in a later japanned frame

21 ¾ in. (55 cm.) high; 29 ½ in. (75 cm.) wide

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

SECOND HALF 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular bevelled plate depicting a lakeside view with a bearded man seated beneath a tree and a lady holding a basket of flowers, with buildings and mountains beyond, in an 18th-century pierced and foliate-carved giltwood frame, altered to fit, re-gilt

32 ¼ in. (82 cm.) high; 46 ¾ in. (119 cm.) wide, including frame

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-PAINTED MIRROR

LATE 18TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting a seated woman holding a watch, beneath a floral garland, within a bead-and-reel and ribbon-carved giltwood frame with ribbon-tied cresting

23 ¼ in. (46 cm.) high; 16 in. (34.5 cm.) wide, overall

A CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE-MIRROR PAINTING

LATE 18TH/EARLY 19TH CENTURY

The rectangular plate depicting Clairon and Melpomene, Clairon seated with volumes by Corneille, Racine, Voltaire and Crebillon beside her, Pegasus and a tempietto beyond, in a painted border simulating a frame, with ribbon-tied laurel garland, inscribed 'PROPHETIE ACOMPLIE.', the lower edge inscribed 'J'ai prédit que CLAIRON illustreroit la Scene Et mon espoire n'a pomtété decu: Ella a couronné Melpomene, Melpomene lui rend cequelle en a recu. GARRICK.', enclosed by a border of trailing flowers, in a 19th century giltwood frame

14 in. (35.5 cm.) high; 11 ¾ in. (30 cm.) wide

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's Londres - Vente du 23 juillet 2020

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Superbe, merci pour cette belle présentation.

Lucius- Messages : 11656

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Age : 33

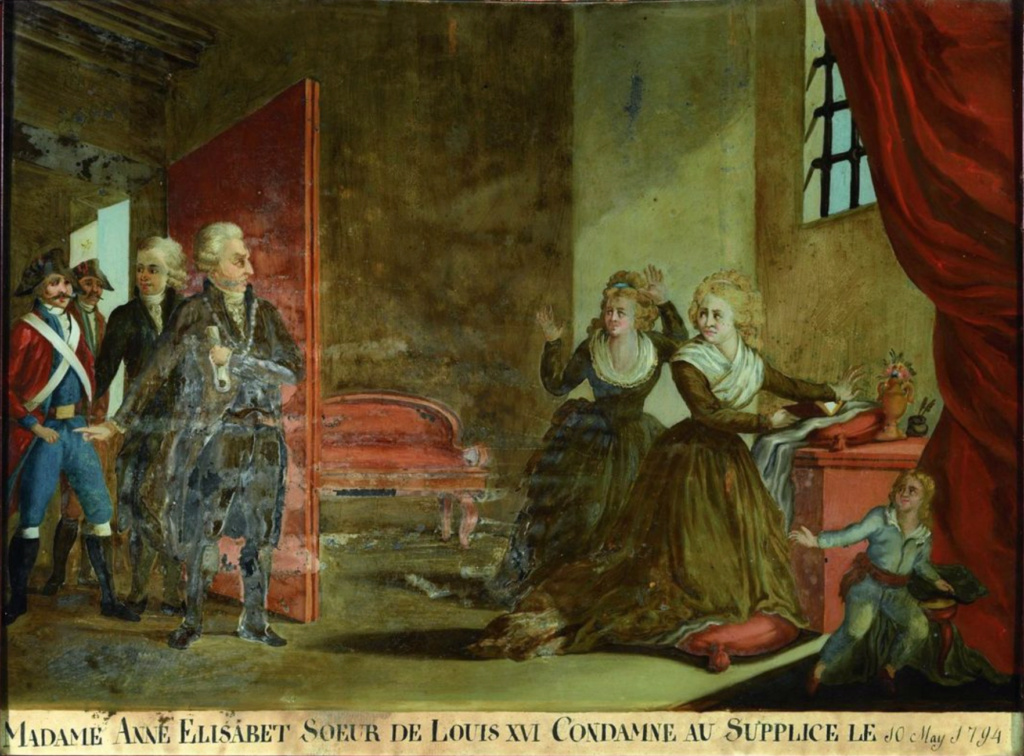

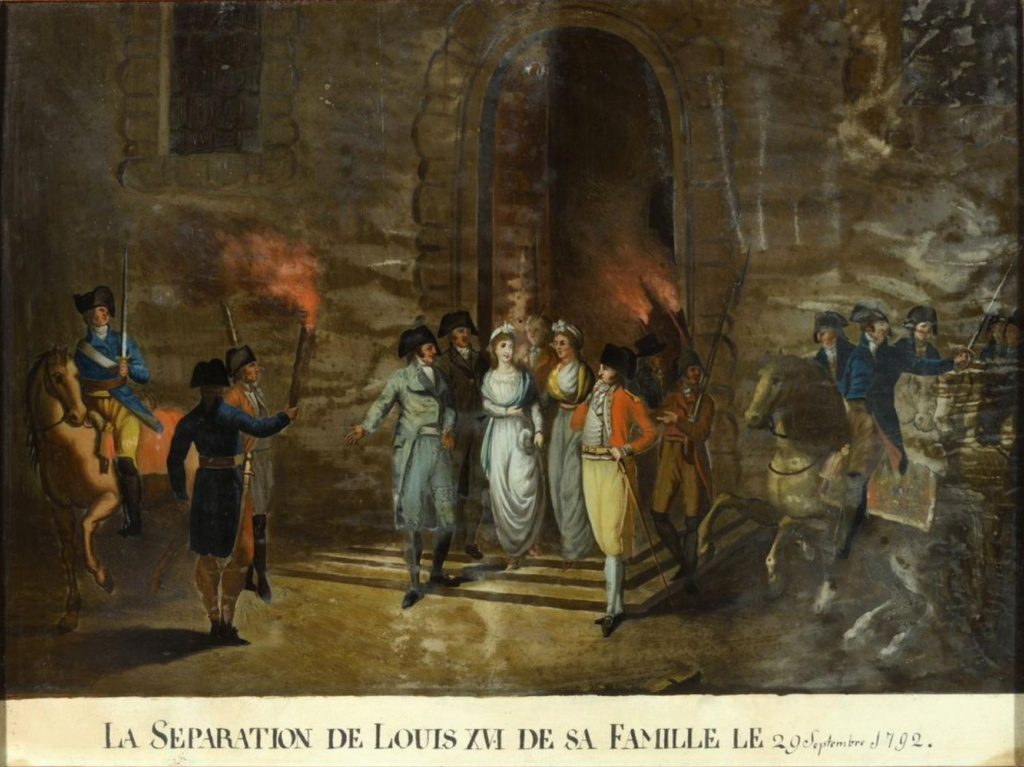

Fixés sous verre illustrant la fin de la monarchie française

Fixés sous verre illustrant la fin de la monarchie française

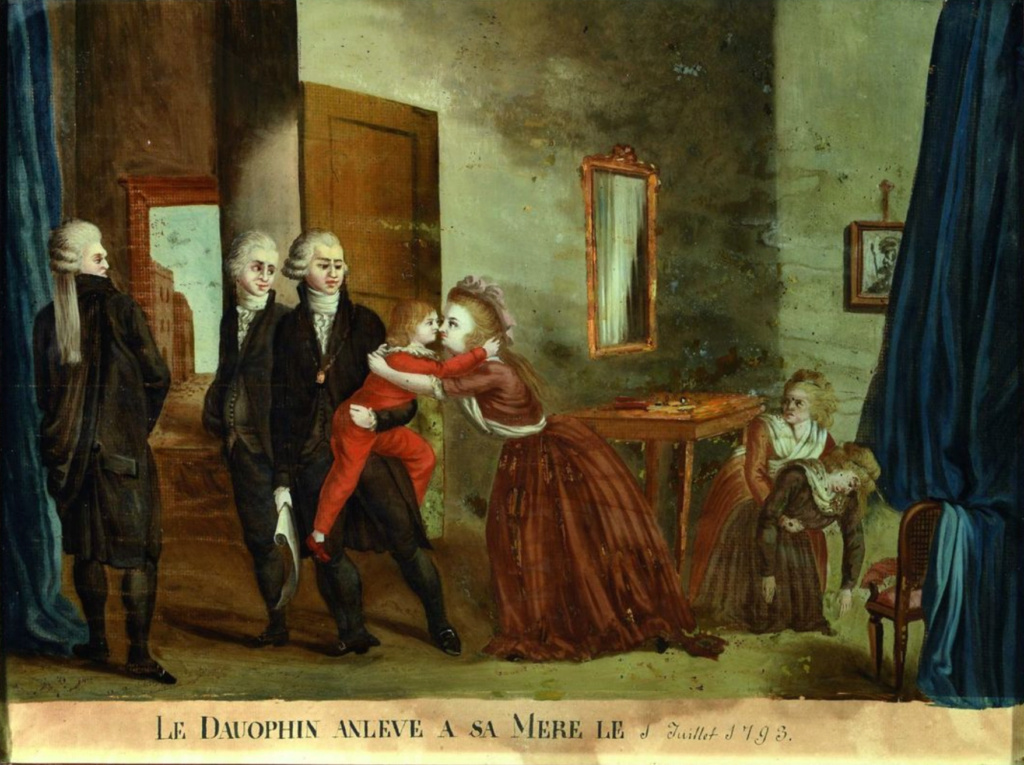

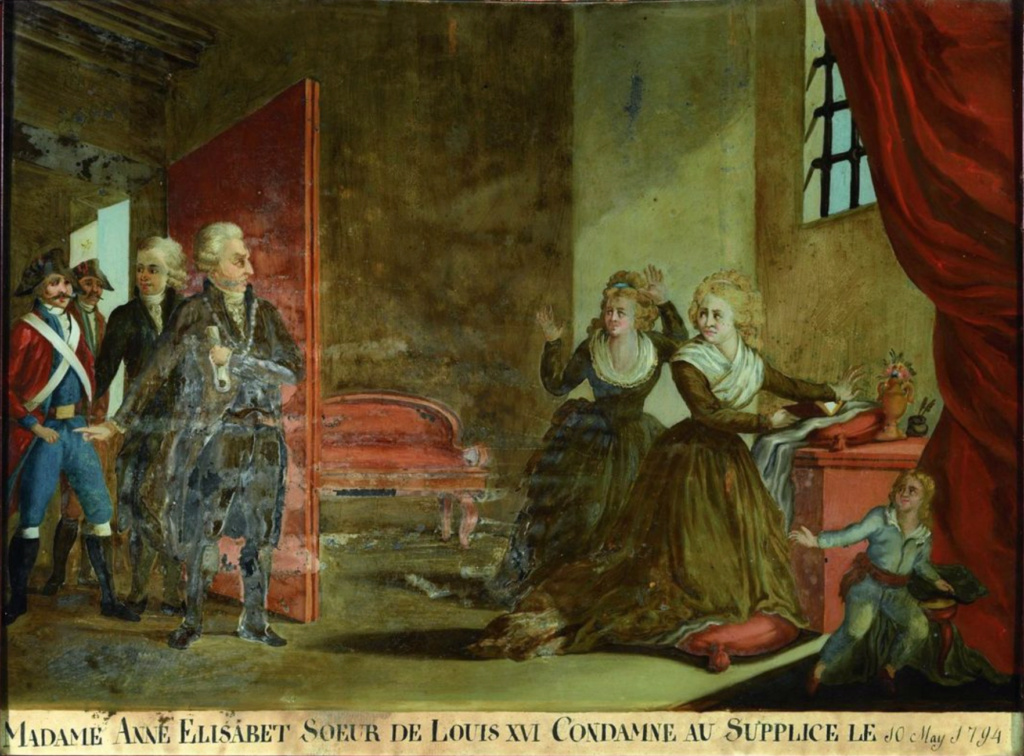

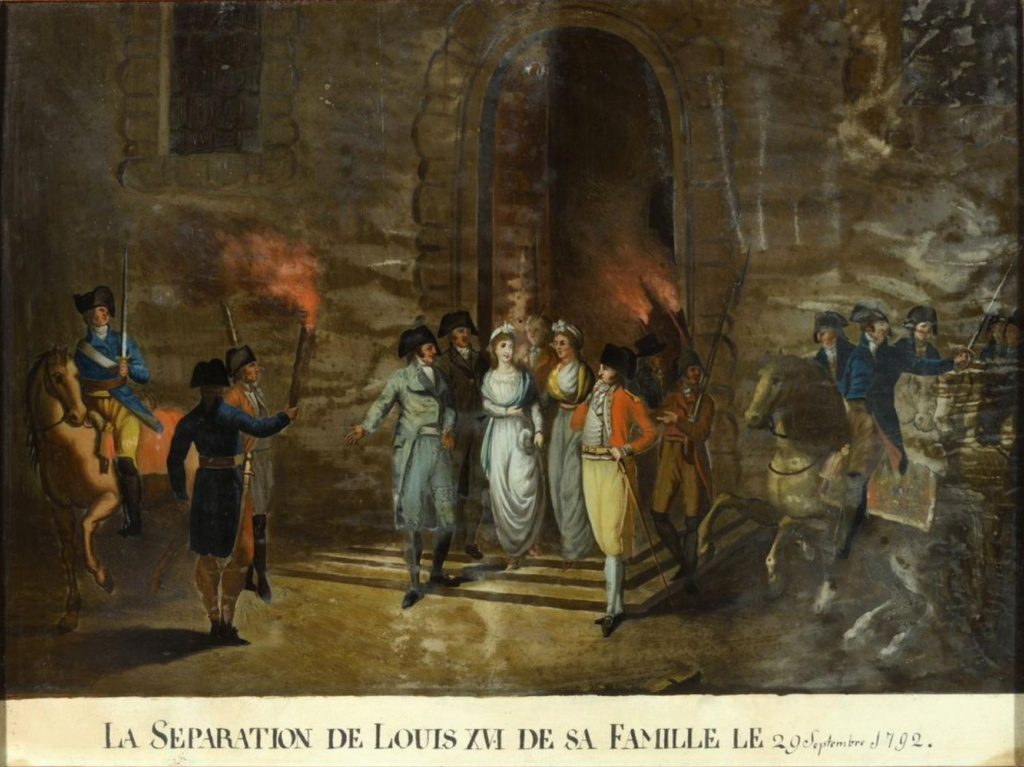

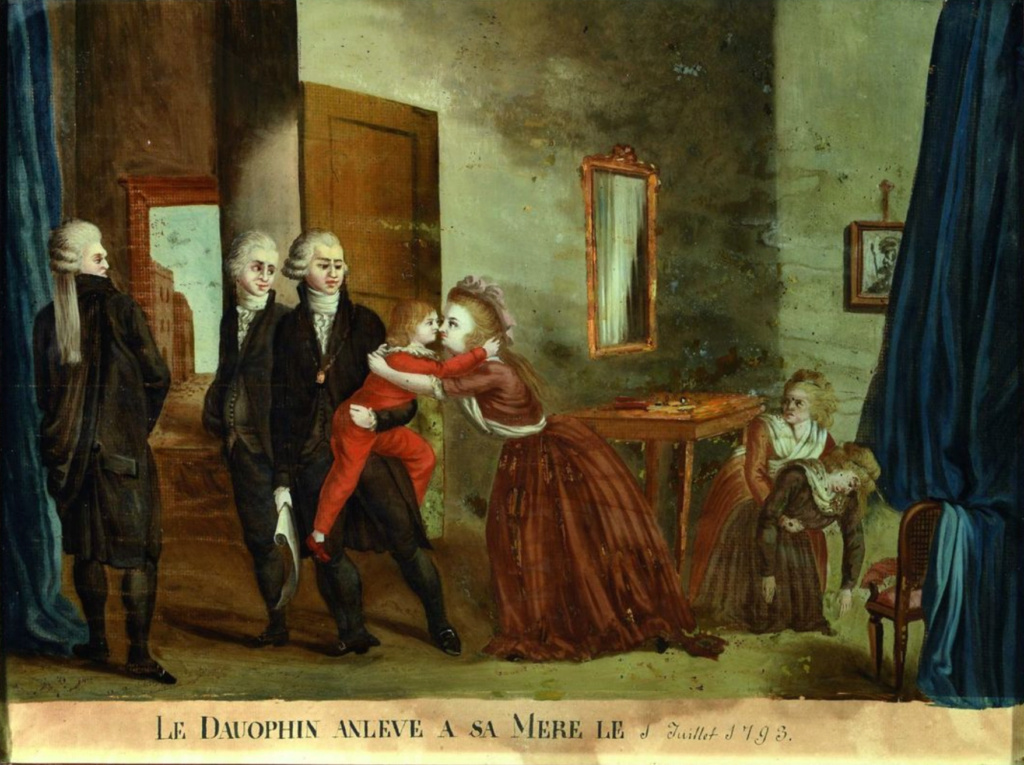

Voici un rare ensemble de " fixés sous verre " illustrant des événements de la Révolution. Nous les connaissons plutôt sous la forme d'estampes ou de dessins.

Cet ensemble sera prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères. Je cite des extraits de la présentation (et zappe les cadres sur la plupart des images).

EXCEPTIONNEL ENSEMBLE DE DOUZE FIXES SOUS VERRE REPRESENTANT LES DIFFERENTES ETAPES DE LA FIN DE LA MONARCHIE FRANCAISE

1.Arrestation de Louis XVI à varennes (le 22 juin 1791)

2. Retour de varennes arrivée de Louis XVI à Paris le 25 juin 1791

3. La Séparation de Louis XVI et de sa Famille le 29 Septembre 1792. (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11)

4. La 2e Séparation ou dernier Adieu du Roy d'avec sa Famille désolée le 20 Janvier 1793

5. La Dernier Entrevue de Louis XVI avec sa Famille la veille de son Exécution le 20 janvier 1793

6. Le dernier Moment de la vie du Roi Louis XVI le 21 Janvier 1793 Très bel état.

7. Le Dauphin enlevé à sa Mère le 1 Juillet 1793

8. La Reine Marie-Antoinette conduite publiquement ou supplice dans un Tombereau Le 16 Octobre 1793

9. Madame Anne Elisabet Soeur de Louis XVI Condamne au Supplice le 10 May 1794

10. Le dernier Supplice de Madame Elisabet Soeur du Louis XVI le 10 May 1794

11. La Princesse Marie Thérèse Carlotte Fille de Louis XVI part de Paris pour se Rendre en Suisse le 19 Xbre 1795 (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11)

12. Le départ pour Vienne de la Princesse Marie Térèse Charlotte Fille du Roy Louis XVI

Description au catalogue :

La difficile technique de la peinture sous verre est ici parfaitement maîtrisée, les légendes ont été rédigées à part sur des bandes de papier fixées en-dessous, dont nous avons scrupuleusement respecté le graphisme et la rédaction. Celles-ci sont presque toujours identiques aux titres des gravures. (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11).

Ces tragiques évènements ont inspiré de nombreux artistes, parmi lesquels Jean-Louis PRIEUR (1759-1795) auteur de plusieurs dessins à la mine de plomb conservés au Musée Carnavalet, et Charles BENAZECH (1767-1794) pour trois tableaux, dont deux sont conservés au Château de Versailles, lesquels ont été repris en gravure par plusieurs artistes.

Nous avons retrouvé les oeuvres reproduites par notre peintre, il semble évident qu'il a eu sous les yeux toute la série de gravures (les sujets sont inversés par rapport aux originaux : l'artiste copie ce qu'il voit, et le sujet apparaît une fois le verre retourné) :

1. Dessin de Prieur au Musée Carnavalet, nombreuses copies en gravures. Notre artiste n'a retenu que les personnages centraux.

2. Dessin de Prieur au Musée Carnavalet, nombreuses copies en gravures. Notre artiste est resté très proche de l'original.

3. Gravure de Jean Auvril d'après le tableau de Charles Benazech.

4. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech. Gravure de C. Siliano.

5. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech, (au château de Versailles).

6. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech, (au château de Versailles).

7. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

8. Dessin d'Aloisin, gravure de C Siliano.

9. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

10. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

11. Dessin d'Antoine Deif, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

12. Dessin d'Antoine Deif, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

Historique (extraits) :

L'histoire de cet ensemble de fixés sous-verres est aussi incroyable qu'étonnante. Très probablement arrivés dans son équipage lors de l'exil de Marie-Adelaïde de Bourbon, duchesse d'Orléans, accompagnée de son fils, le futur Louis-Philippe Ier, roi des Français, et de Jacques-Marie Rouzet, dont elle était la maîtresse, en décembre 1808.

accompagnée de son fils, le futur Louis-Philippe Ier, roi des Français, et de Jacques-Marie Rouzet, dont elle était la maîtresse, en décembre 1808.

Ils sont restés dans la même famille et n'ont jamais quitté l'île de Minorque depuis plus de deux siècles. Nos douze peintures ont été conservées dans la finca Torre del Rey, propriété de la famille Orfila, à Es Castell. Cette finca fut achetée le 5 mars 1783 au comte de Cifuentes qui était le représentant du Roi d'Espagne à Minorque. Ce domaine fut érigé sur les terrains de l'ancien château de San Felipe, forteresse bâtie au XVIe siècle pour défendre Mahon, la capitale de l'île.

En 1889 les 6 derniers héritiers achetèrent une maison dans Mahon où ils résidèrent tout en gardant la finca entièrement meublée.

(...)

Jamais exposés au public, jamais présentés à la vente, ils sont restés à Minorque jusqu’à ce que nous les découvrions l’année dernière, et reviennent pour la première fois en France.

* Source, descriptif complet, et informations complémentaires : Magin Wedry, Paris - Vente du 9 juillet 2021

Cet ensemble sera prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères. Je cite des extraits de la présentation (et zappe les cadres sur la plupart des images).

EXCEPTIONNEL ENSEMBLE DE DOUZE FIXES SOUS VERRE REPRESENTANT LES DIFFERENTES ETAPES DE LA FIN DE LA MONARCHIE FRANCAISE

1.Arrestation de Louis XVI à varennes (le 22 juin 1791)

2. Retour de varennes arrivée de Louis XVI à Paris le 25 juin 1791

3. La Séparation de Louis XVI et de sa Famille le 29 Septembre 1792. (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11)

4. La 2e Séparation ou dernier Adieu du Roy d'avec sa Famille désolée le 20 Janvier 1793

5. La Dernier Entrevue de Louis XVI avec sa Famille la veille de son Exécution le 20 janvier 1793

6. Le dernier Moment de la vie du Roi Louis XVI le 21 Janvier 1793 Très bel état.

7. Le Dauphin enlevé à sa Mère le 1 Juillet 1793

8. La Reine Marie-Antoinette conduite publiquement ou supplice dans un Tombereau Le 16 Octobre 1793

9. Madame Anne Elisabet Soeur de Louis XVI Condamne au Supplice le 10 May 1794

10. Le dernier Supplice de Madame Elisabet Soeur du Louis XVI le 10 May 1794

11. La Princesse Marie Thérèse Carlotte Fille de Louis XVI part de Paris pour se Rendre en Suisse le 19 Xbre 1795 (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11)

12. Le départ pour Vienne de la Princesse Marie Térèse Charlotte Fille du Roy Louis XVI

Description au catalogue :

La difficile technique de la peinture sous verre est ici parfaitement maîtrisée, les légendes ont été rédigées à part sur des bandes de papier fixées en-dessous, dont nous avons scrupuleusement respecté le graphisme et la rédaction. Celles-ci sont presque toujours identiques aux titres des gravures. (Il y a eu à l'époque interversion des bandes-titres n° 3 et 11).

Ces tragiques évènements ont inspiré de nombreux artistes, parmi lesquels Jean-Louis PRIEUR (1759-1795) auteur de plusieurs dessins à la mine de plomb conservés au Musée Carnavalet, et Charles BENAZECH (1767-1794) pour trois tableaux, dont deux sont conservés au Château de Versailles, lesquels ont été repris en gravure par plusieurs artistes.

Nous avons retrouvé les oeuvres reproduites par notre peintre, il semble évident qu'il a eu sous les yeux toute la série de gravures (les sujets sont inversés par rapport aux originaux : l'artiste copie ce qu'il voit, et le sujet apparaît une fois le verre retourné) :

1. Dessin de Prieur au Musée Carnavalet, nombreuses copies en gravures. Notre artiste n'a retenu que les personnages centraux.

2. Dessin de Prieur au Musée Carnavalet, nombreuses copies en gravures. Notre artiste est resté très proche de l'original.

3. Gravure de Jean Auvril d'après le tableau de Charles Benazech.

4. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech. Gravure de C. Siliano.

5. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech, (au château de Versailles).

6. Reprend très exactement le tableau de Charles Benazech, (au château de Versailles).

7. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

8. Dessin d'Aloisin, gravure de C Siliano.

9. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

10. Dessin de Domenico Pellegrini, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

11. Dessin d'Antoine Deif, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

12. Dessin d'Antoine Deif, gravure de Carlo Lasinio.

Historique (extraits) :

L'histoire de cet ensemble de fixés sous-verres est aussi incroyable qu'étonnante. Très probablement arrivés dans son équipage lors de l'exil de Marie-Adelaïde de Bourbon, duchesse d'Orléans,

Ils sont restés dans la même famille et n'ont jamais quitté l'île de Minorque depuis plus de deux siècles. Nos douze peintures ont été conservées dans la finca Torre del Rey, propriété de la famille Orfila, à Es Castell. Cette finca fut achetée le 5 mars 1783 au comte de Cifuentes qui était le représentant du Roi d'Espagne à Minorque. Ce domaine fut érigé sur les terrains de l'ancien château de San Felipe, forteresse bâtie au XVIe siècle pour défendre Mahon, la capitale de l'île.

En 1889 les 6 derniers héritiers achetèrent une maison dans Mahon où ils résidèrent tout en gardant la finca entièrement meublée.

(...)

Jamais exposés au public, jamais présentés à la vente, ils sont restés à Minorque jusqu’à ce que nous les découvrions l’année dernière, et reviennent pour la première fois en France.

* Source, descriptif complet, et informations complémentaires : Magin Wedry, Paris - Vente du 9 juillet 2021

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

Re: La peinture sous et sur verre au 18e siècle, et la technique du verre églomisé

C'est un bel exemplaire de miroir décoré de peintures sous verre importées de Chine qui sera prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères :

A GEORGE II GILTWOOD OVERMANTEL MIRROR INSET WITH CHINESE EXPORT REVERSE MIRROR PAINTINGS

CIRCA 1760

The shaped plates within a gilt foliate scroll frame, the outer panels decorated with scenes of landscapes, colorfully plumed birds, flora and fauna

58 in. (147.5 cm.) high, 73 in. (185.5 cm.) wide

Lot Essay

This monumental mirror is remarkable not only for its unusually large scale but equally for its elaborate scene painting within a beautifully drawn giltwood frame. The frame follows the designs of London's pre-eminent cabinet-makers such as John Linnell or Thomas Chippendale. The pairing of reverse painted mirror glass with flat glass represents the ingenuity and collaboration between Chinese and British artists of the mid-18th century.

THE ART OF CHINESE MIRROR PAINTING

The practice of painting on mirrors developed in China after 1715 when the Jesuit missionary Father Castiglione arrived in Beijing. He found favor with the Emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong and was entrusted with the decoration of the Imperial Garden in Beijing. He learned to paint in oil on glass, a technique that was already practiced in Europe but which was unknown in China in 1715.

Chinese artists, already expert in painting and calligraphy, took up the practice, tracing the outlines of their designs on the back of the plate and, using a special steel implement, scraping away the mirror backing to reveal glass that could then be painted.

Glass paintings were made almost entirely for export, fueled by the mania in Europe for all things Chinese. Although glass vessels had long been made in China, the production of flat glass was not accomplished until the 19th century. Even in the Imperial glass workshops, set up in Beijing in 1696 under the supervision of the Bavarian Jesuit Kilian Stumpf, window glass or mirrored glass was not successfully produced. As a result, from the middle of the 18th century onwards, when reverse glass painting was already popular in Europe, sheets of both clear and mirrored glass were sent to Canton from Europe. They most often depicted bucolic landscapes, frequently with sumptuously dressed Chinese figures at leisurely pursuits. Once in Europe the best were often placed in elaborate giltwood Chippendale or Chinoiserie frames.