Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

+2

Comtesse Diane

Mme de Sabran

6 participants

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La France et le Monde au XVIIIe siècle :: Histoire et événements ailleurs dans le monde

Page 1 sur 1

Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

...................................

Gageons que ces dames ont admiré cette vue splendide ! :n,,;::::!!!:

Thermes de Bath

Roman Baths

Le complexe des Thermes de Bath est un site d'intérêt historique dans la ville anglaise de Bath. Le lieu est un site de baignade publique romain bien conservé.

Les thermes romains eux-mêmes sont en dessous du niveau de la rue moderne. Ils comportent quatre points d'intérêts principaux : la source sacrée ; le temple romain ; les thermes et le musée regroupant les artéfacts trouvés lors de fouilles. Les bâtiments situés au niveau de la rue datent du XIXe siècle.

Les termes sont une attraction majeur du tourisme en Angleterre, en particulier, le Grand Pump Room (en) reçoit plus d'un million de visiteurs par an1 dont 1 037 518 personnes en 2009.

Autrefois en général et à l'époque qui nous intéresse en particulier ( : ) , les bains étaient considérés comme un traitement pour beaucoup de maladies chroniques.

) , les bains étaient considérés comme un traitement pour beaucoup de maladies chroniques.

Sources de l'eau

L'eau qui bouillonne dans le sous-sol de Bath provient des précipitations tombées sur les Collines de Mendip. Elle s'infiltre à travers un aquifère calcaire jusqu'à une profondeur de 2700 à 4300 m où l'énergie géothermique élève sa température entre 64 et 96°. Sous la pression, l'eau chaude remonte à la surface le long de fissures et de failles dans la roche calcaire.

Un peu d'histoire ! :n,,;::::!!!:

Les Celtes sont les premiers à construire un sanctuaire sur le site des eaux chaudes. Ils le dédient à la déesse Sulis (en) que les romains identifient à leur déesse Minerve.

Geoffroy de Monmouth, dans son Historia regum Britanniae, décrit comment la source est découverte en 836 av. J.-C. par Bladud, le roi des Bretons insulaires, qui y construit les premiers bains.

Au XVIIIe siècle, la légende obscure de Geoffroy prend une grande importance et s'embellit pour apporter une approbation royale de la qualité des eaux. La boue et la source d'eau chaude ayant guéri Bladud et ses porcs de la lèpre.

Époque romaine

Le nom « Sulis » continue à être utilisé après l'invasion romaine, donnant le nom romain de la ville, Aquae Sulis (en), la ville de Sulis. Le temple est construit vers 60-70, tandis que le complexe thermal est construit progressivement durant les 300 années suivantes.

Les thermes ont été modifiés à plusieurs occasions, notamment au XIIe siècle quand Jean de Tours construit un bassin curatif et au XVIe siècle quand la corporation de la ville construit un nouveau bassin (le bain de la reine) au sud de la source .

La source est désormais dans des bâtiments du XVIIIe siècle, conçus par les architectes John Wood, l'ainé (en) et John Wood, le jeune (en), le père et le fils. Les visiteurs peuvent prendre les eaux au Grand Pump Room (en), salon à l'architecture néo-classique toujours utilisé.

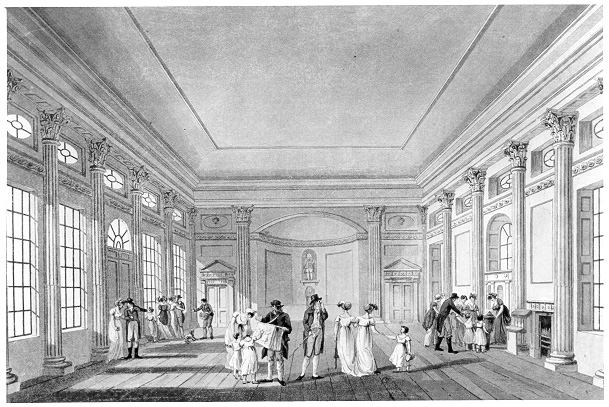

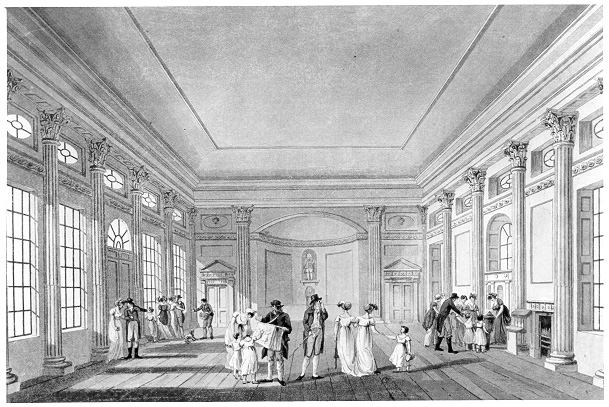

The Grand Pump Room avant les travaux ( l'on se croirait à Lourdes ! ) :

Thomas Rowlandson - Comforts of Bath- The Pump Room

Mme de Polignac n'a connu que ce premier ( ci-dessus ) Pump Room, car les travaux sont commencés en 1789 par Thomas Baldwin pour créer cette nouvelle magnifique Grand Pump Room ...

... où Mme de Lamballe s'est certainement promenée car, au moment de la Révolution, elle consent à fuir en Angleterre sur les instances de son beau-père le duc de Penthièvre.

Monsieur de Penthièvre à sa bru :

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; ***

Mais aux temps heureux d'avant la Révolution, Mmes de Lamballe et de Polignac, toutes deux de complexion fragile, s'étaient rendues à Bath pour goûter les bienfaits curatifs de ses eaux .

Clio s'est faite notre envoyée spéciale sur les lieux et a recherché pour nous les maisons qu'avaient habitées la duchesse et la princesse.

Clio a écrit :

Madame de Lamballe louait le 1 Royal Crescent , c'est un musée maintenant, une maison XVIII où nous avons eu le grand plaisir d'être conviés en costumes .

Une de mes amis est guide à Bath et écrivain spécialiste de cette ville merveilleuse ; je lui ai demandé des renseignements sur le séjour de Madame de Polignac .

Aussitôt reçus, je vous en fais profiter, of course ...

The Royal Crescent ( Croissant royal ) :

Le premier au 1 Royal Crescen est actuellement un hôtel et le second un musée .

Malheureusement, poursuit notre Clio, je n'ai guère de détails, malgré mes recherches....

Le logement de Mme de Lamballe est vaste ; nous ne savons pas exactement comment était celui des Polignac .

Bath recevait beaucoup de personnes riches et célèbres et ces logis devaient être très agréables.

Mais non, je n'ai pas dormi dans un lit historique cette fois ci ! :

Le 1 Royal Crescent à Bath:

Cette superbe maison était encore divisée en appartements (on y trouvait même un cabinet dentaire), il y a 15 ans environ! L'immeuble entier, racheté par une fondation, a été magnifiquement restauré. Les sash windows à petits bois ont été refaites à l'identique etc...

L'intérieur n'est cependant pas une restitution, mais une recréation si parfaite d'une maison géorgienne que l'on s'attendrait à y trouver Mme de Lamballe partaking tea with the Duchess of Devonshire!

Kiki :

Rassurez-moi, ClioXVIIII , le bon docteur Seiffert voisinait de loin ? Les mauvaises langues se déchaînaient à Paris ! A tel point que Marie-Antoinette a exigé le retour de Marie-Thérèse (le docteur sur ses talons). Pourtant les bains lui faisaient beaucoup de bien

Clio :

J'ignore si la réputation curative de Bath était surfaite, mais elle était déjà prônée et goûtée par les Romains. Et sa mode avait duré depuis lors (avec probablement une éclipse au Moyen-âge). Mme de Polignac avait aussi apprécié les bienfaits de ses bains .

Il fallait du courage, ou être très mal, pour se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoutante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez . Ensuite, une chaise à porteurs vous reconduisait dans votre appartement en location . Mais, à part ces bains , quelle vie mondaine !

Des thermes à l'entrée fort onéreuse mais très plaisants ont ouvert après un délai très long pour cause de malfaçon dans les peintures . Se baigner en plein air avec vue sur la cathédrale dans de l'eau chaude (et sans odeur ) est très plaisant.

Kiki :

Voici un texte de Bath sur le séjour des Polignac que m'a envoyé Clio XVIII :

The Regional Historian: Journal of the Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol, no.18, summer 2008, pp.33-36

A Brush with the Ancien Régime: French Courtiers at Bath in 1787

Trevor Fawcett

The cure – or curiosity – brought a trickle of international gentry to Bath all through the eighteenth century, but until the 1780s rather few of them French. Those cross-Channel visitors who did arrive tended to have business in mind, especially after 1765 when the Bath city freemen, after decades of strenuous opposition to interlopers, finally lost their ancient trading monopolies. Over the next twenty-five years dozens of French nationals – mostly dealers in luxury gods or providers of specialist services – tried their luck at Europe’s fastest growing spa, among them jewellers and toymen, hairdressers and perfumers, milliners, staymakers, dentists, language teachers and dancing masters. Some, finding the milieu congenial, settled. Others relied on seasonal visits. Either way Bath offered rich pickings. The city’s political loyalties might be ostentatiously Hanoverian, but in matters of fashion, especially women’s, it was still Paris that dictated. And on a wider front, too, French culture and language had status value. French tutors found ready employment; the circulating libraries stocked foreign authors; and Antoine Le Texier, well known in London for his French play-readings, performed to appreciative - and presumably francophone - audiences on his repeated visits to Bath from the 1780s onwards.

About the same period, as diplomatic relations defrosted in the aftermath of the American War, the number of overseas visitors listed among the spa arrivals, French included, began to increase. The French ambassador himself, Adhémar de Montfalcon, paid a health visit in April 1785 and was back again in 1786. The same year the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, Marie Antoinette’s brother, caused rather more of a stir when he and his entourage stopped two nights at the York House, Bath’s top hotel. The Anglo-French trade treaty signed in September 1786 not only boosted the displays of French cambrics, wines and candles in the shops, it probably accounted for another small influx of French notables during an unusually brilliant autumn and winter season. Certainly the treaty was assumed by the Bath Chronicle to have brought to England, and then to Bath, a particularly distinguished French party the following spring – the Polignacs and Vaudreuils no less, intimates and favourites of Marie Antoinette for the past twelve years. They arrived in May 1787 accompanied by the French and Spanish ambassadors and also Prince Rezzonico, one of Archduke Ferdinand’s entourage from the previous year. It was evidently no casual visit. Two large lodging houses on North Parade had been hired in advance to serve as the party’s base for well over a month while they enjoyed the spa diversions, called on nearby country houses, and by report dispensed louis d’ors in liberal quantities. Such an unprecedented stay by foreign aristocracy set tongues wagging. Might the motive not be the commercial treaty after all, but the fact that the Polignacs were temporarily out of favour with the French Queen for siding with the recently dismissed minister of finance Calonne, whom she had always disliked and opposed? Or was their own explanation, offered to the Marquis Lansdowne during an outing to Bowood, not perfectly plausible – that they had simply come for the cure? Or were they actually serving Marie Antoinette in some way?

The Archduke Ferdinand’s visit in September 1786 had followed his earlier stay at Versailles at the height of the ‘diamond necklace’ scandal - an affair that did Marie Antoinette so much damage, innocent in this case though she was. The plot was almost farcical. A fabulous necklace had been sold by the court jeweller to the gullible cardinal de Rohan, the late French ambassador in Vienna, anxious to ingratiate himself with the Queen after long being out of favour. Rohan had been tricked into believing that the Queen coveted the necklace, and would pay for it, by a certain Jeanne de la Motte, self-styled comtesse de Valois, who fed him forged letters and arranged a nocturnal meeting with a prostitute feigning to be the Queen. Wanting payment for the necklace, the jeweller unwittingly brought the plot to light, but at Rohan’s subsequent trial before the Paris Parlement in May 1786 he and his associate, the mysterious comte de Cagliostro, were acquitted and only Jeanne de la Motte was sentenced to flogging, branding, and imprisonment in the Salpêtrière. The outcome of the trial, the outpouring of pamphlets, the charges and counter-charges, the public emotions stirred up by all the scurrilous, prurient innuendo, fatally undermined the Queen’s already profligate reputation, and the affair was still festering when the Polignac party came to Bath. Indeed there were fresh complications. Jeanne de la Motte’s husband, having fled to Britain, had been selling off jewels from the necklace and negotiating with Versailles, via the ambassador Adhémar, over his threat to incriminate the Queen still further. In London he associated with other malcontents, among them the exiled Cagliostro whose own best-selling account, The Queen of France’s Necklace, had been available at one Bath bookshop since as early as April 1786. Meanwhile the Polignacs’ ally (but Marie Antoinette’s adversary), Charles Alexandre Calonne, had been dismissed from his key government post as finance minister. Privy to many Court secrets and ready to pen his own self-justification, the Requête au Roi, he too soon turned up in London and eventually in Bath.

With alarm bells ringing at Versailles about the possibility of more revelations, true or not, the Polignac contingent set out for England in early May 1787, ostensibly on a health trip but probably too in the hope of buying silence from their dangerous compatriots in exile. Although the party travelled first to London, their ultimate destination of Bath was well enough known beforehand to William Eden, Britain’s trade negotiator in France, who guessed that ‘the novelty of the [Bath] scene will amuse them while the novelty exists, but they will grow tired’. He noted, however, that they were all fond of gambling, and Bath could well provide for that. Eden regarded the expedition as mainly for pleasure and assumed they would ‘all be chiefly in the Duchess of Devonshire’s society’, knowing the long-standing friendship between the Devonshires and Polignacs which had indeed almost persuaded the duchesse de Polignac to Bath, a favourite haunt of the Devonshires, the year before.

Reaching London on 6 May they met up at once with their old protégé Adhémar and attended the ambassador’s grand assembly the same evening. Two days later, having used the Duchess of Devonshire’s box at the opera, they attended her supper and ball, and on 12 May set out for Bath. En route they spent a night at Stowe and possibly also at Blenheim. Certainly Diane comtesse de Polignac halted at Blenheim, along with Spanish ambassador, these joining the main party at Bath some days later. This brought the company, excluding servants, up to twelve - the duc and duchesse (Yolande) de Polignac, their headstrong sister-in-law Diane de Polignac, their daughter and son-in-law (duc de Guiche), the comte, vicomte and vicomtesse de Vaudreuil, and the diplomatic quartet of Adhémar, two Spaniards (the earl of Polentinos and chevalier Colmenares ), and prince Rezzonico, there presumably to represent Habsburg interests in the French Queen’s affairs. As Eden had predicted, their chief hosts at Bath seem to have been the Devonshires, in whose company they graced the pleasure gardens one evening, though it was Adhémar who escorted them (with the Bishop of Winchester) to view the apothecary William Sole’s botanic garden on the outskirts of town. Details of their movements are otherwise scanty, apart from the already mentioned excursion to Bowood and another to Stourhead and Salisbury. Any negotiations that might have taken place with La Motte remain undocumented – but there is other evidence.

In June 1787 Jeanne de la Motte escaped from the Salpêtrière prison so mysteriously that it seemed only government collusion could explain it. Contemporary diplomatic letters went further. The ‘escape’, it was claimed, was the direct fruit of the Polignac-Vaudreuil jaunt to Bath, where the comte de la Motte had stipulated, in addition to his wife’s release, a price of 4000 louis d’or for handing over a libellous memoir and correspondence supposedly exchanged between cardinal de Rohan and the Queen herself – a price so much higher than expected that the Polignacs had been obliged to dispatch a courier to Versailles to hurry extra funds to England, hence the unexpected long sojourn at Bath and the relieved welcome the duchesse de Polignac received on her return to court with the incendiary documents.

The Polignac-Vaudreuil party, though not the Devonshires, had finally quitted Bath on 16 June and were back at Versailles in about ten days. Their joyous reception soon turned sour. By July the Devonshires were being informed that the duchesse de Polignac had been supplanted by the former favourite (and superintendant of the Queen’s household), the princesse de Lamballe. Perhaps more to the point was the dawning realisation that the mission to prevent unsavoury revelations being broadcast from England had failed. While the potentially damaging letters had been retrieved, the double-dealing comte de la Motte, it was said, had withheld legally attested copies. What was beyond doubt was that the comte would soon be reunited in England with his wife, who also had a tale to tell.

Within days, therefore, a fresh pre-emptive mission was planned, this time headed by the reliable princesse de Lamballe who briskly left for London with her suite in early July. Her rather public and ceremonious stay in England cannot have settled matters, however, for a second, more private visit took place two months later - by which time Jeanne de la Motte and the ex-minister Calonne were both in London and, furthermore, in mutual contact. Thinly disguised under the title ‘comtesse d’Amboise’, the princesse de Lamballe landed at Southampton on 19 September 1787 and reached Bath, again ‘with a numerous retinue’, on the 21st, having called at Lord Palmerston’s Romsey seat en route. The conjecture abroad was that her rendezvous at Bath was with Calonne in person – and Calonne surely must already have known Bath when he chose it, eight months later, as the place for his marriage to his wealthy mistress, Mme d’Harvelay. The presence of the Austrian diplomat, prince Reuss, among the princesse’s advisors lends credence to the view that Calonne was in a position to implicate Marie Antoinette over secret financial transactions with Vienna. In fact his manuscript, copies of which the princesse apparently took back to Versailles, was silent on such matters. Indeed, desperate to regain royal favour, Calonne bent all his efforts over the next few years into shielding the Queen from criticism, becoming embroiled in blackmailing the La Motte couple in the process, as he periodically lamented in his letters to the duchesse de Polignac. Ultimately he failed and Jeanne de la Motte’s notoriously self-serving Mémoires appeared with some noise in late 1788.

The visits paid to Bath by high-standing French emissaries and key foreign ambassadors at this time points to special diplomatic and court concerns on the eve of the French Revolution. Precisely what was transacted there remains speculative, though efforts at damage limitation on behalf of the French Queen seem to have been at the heart of it. If so, the missions largely failed. The wounding publications were not halted and her reputation crumbled further. Moreover, from Bath’s point of view this brush with the Ancien Régime turned out to be merely a prelude. The courtiers had been and gone. Next came the Revolution and with it the many fugitive émigrés who found sanctuary at Bath over the next two decades and more.

Tous en choeur :

Merci, merci, chère Clio !!! :n,,;::::!!!: :n,,;::::!!!: :n,,;::::!!!:

Clio :

Redde caesarea quod caesaris et à Trévor ce qui appartient à Trevor .

Kiki :

C'est palpitant ! Mais, ce n'est pas forcément à prendre au pied de la lettre dans tous les détails, puisque notamment, la Reine est largement incriminée et passe pour avoir organisé l'évasion de la Motte ! C'est du pur délire !!! C'est admettre qu'elle a trempé dans l'affaire du Collier !

On y voit combien les Polignac et les Devonshire étaient liés, et Mme de Lamballe repasser la Manche à la rescousse, les Polignac n'ayant pas entièrement réussi dans leur mission pour contrer la publications des mémoires de la Motte ... Que fabrique Calonne dans tout cela ???

.......................................... FIN DE CE BOUTURAGE !

.........................

.

Gageons que ces dames ont admiré cette vue splendide ! :n,,;::::!!!:

Thermes de Bath

Roman Baths

Le complexe des Thermes de Bath est un site d'intérêt historique dans la ville anglaise de Bath. Le lieu est un site de baignade publique romain bien conservé.

Les thermes romains eux-mêmes sont en dessous du niveau de la rue moderne. Ils comportent quatre points d'intérêts principaux : la source sacrée ; le temple romain ; les thermes et le musée regroupant les artéfacts trouvés lors de fouilles. Les bâtiments situés au niveau de la rue datent du XIXe siècle.

Les termes sont une attraction majeur du tourisme en Angleterre, en particulier, le Grand Pump Room (en) reçoit plus d'un million de visiteurs par an1 dont 1 037 518 personnes en 2009.

Autrefois en général et à l'époque qui nous intéresse en particulier ( :

) , les bains étaient considérés comme un traitement pour beaucoup de maladies chroniques.

) , les bains étaient considérés comme un traitement pour beaucoup de maladies chroniques.Sources de l'eau

L'eau qui bouillonne dans le sous-sol de Bath provient des précipitations tombées sur les Collines de Mendip. Elle s'infiltre à travers un aquifère calcaire jusqu'à une profondeur de 2700 à 4300 m où l'énergie géothermique élève sa température entre 64 et 96°. Sous la pression, l'eau chaude remonte à la surface le long de fissures et de failles dans la roche calcaire.

Un peu d'histoire ! :n,,;::::!!!:

Les Celtes sont les premiers à construire un sanctuaire sur le site des eaux chaudes. Ils le dédient à la déesse Sulis (en) que les romains identifient à leur déesse Minerve.

Geoffroy de Monmouth, dans son Historia regum Britanniae, décrit comment la source est découverte en 836 av. J.-C. par Bladud, le roi des Bretons insulaires, qui y construit les premiers bains.

Au XVIIIe siècle, la légende obscure de Geoffroy prend une grande importance et s'embellit pour apporter une approbation royale de la qualité des eaux. La boue et la source d'eau chaude ayant guéri Bladud et ses porcs de la lèpre.

Époque romaine

Le nom « Sulis » continue à être utilisé après l'invasion romaine, donnant le nom romain de la ville, Aquae Sulis (en), la ville de Sulis. Le temple est construit vers 60-70, tandis que le complexe thermal est construit progressivement durant les 300 années suivantes.

Les thermes ont été modifiés à plusieurs occasions, notamment au XIIe siècle quand Jean de Tours construit un bassin curatif et au XVIe siècle quand la corporation de la ville construit un nouveau bassin (le bain de la reine) au sud de la source .

La source est désormais dans des bâtiments du XVIIIe siècle, conçus par les architectes John Wood, l'ainé (en) et John Wood, le jeune (en), le père et le fils. Les visiteurs peuvent prendre les eaux au Grand Pump Room (en), salon à l'architecture néo-classique toujours utilisé.

The Grand Pump Room avant les travaux ( l'on se croirait à Lourdes ! ) :

Thomas Rowlandson - Comforts of Bath- The Pump Room

Mme de Polignac n'a connu que ce premier ( ci-dessus ) Pump Room, car les travaux sont commencés en 1789 par Thomas Baldwin pour créer cette nouvelle magnifique Grand Pump Room ...

... où Mme de Lamballe s'est certainement promenée car, au moment de la Révolution, elle consent à fuir en Angleterre sur les instances de son beau-père le duc de Penthièvre.

Monsieur de Penthièvre à sa bru :

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; ***

Mais aux temps heureux d'avant la Révolution, Mmes de Lamballe et de Polignac, toutes deux de complexion fragile, s'étaient rendues à Bath pour goûter les bienfaits curatifs de ses eaux .

Clio s'est faite notre envoyée spéciale sur les lieux et a recherché pour nous les maisons qu'avaient habitées la duchesse et la princesse.

Clio a écrit :

Madame de Lamballe louait le 1 Royal Crescent , c'est un musée maintenant, une maison XVIII où nous avons eu le grand plaisir d'être conviés en costumes .

Une de mes amis est guide à Bath et écrivain spécialiste de cette ville merveilleuse ; je lui ai demandé des renseignements sur le séjour de Madame de Polignac .

Aussitôt reçus, je vous en fais profiter, of course ...

The Royal Crescent ( Croissant royal ) :

Le premier au 1 Royal Crescen est actuellement un hôtel et le second un musée .

Malheureusement, poursuit notre Clio, je n'ai guère de détails, malgré mes recherches....

Le logement de Mme de Lamballe est vaste ; nous ne savons pas exactement comment était celui des Polignac .

Bath recevait beaucoup de personnes riches et célèbres et ces logis devaient être très agréables.

Mais non, je n'ai pas dormi dans un lit historique cette fois ci ! :

Le 1 Royal Crescent à Bath:

Cette superbe maison était encore divisée en appartements (on y trouvait même un cabinet dentaire), il y a 15 ans environ! L'immeuble entier, racheté par une fondation, a été magnifiquement restauré. Les sash windows à petits bois ont été refaites à l'identique etc...

L'intérieur n'est cependant pas une restitution, mais une recréation si parfaite d'une maison géorgienne que l'on s'attendrait à y trouver Mme de Lamballe partaking tea with the Duchess of Devonshire!

Kiki :

Rassurez-moi, ClioXVIIII , le bon docteur Seiffert voisinait de loin ? Les mauvaises langues se déchaînaient à Paris ! A tel point que Marie-Antoinette a exigé le retour de Marie-Thérèse (le docteur sur ses talons). Pourtant les bains lui faisaient beaucoup de bien

Clio :

J'ignore si la réputation curative de Bath était surfaite, mais elle était déjà prônée et goûtée par les Romains. Et sa mode avait duré depuis lors (avec probablement une éclipse au Moyen-âge). Mme de Polignac avait aussi apprécié les bienfaits de ses bains .

Il fallait du courage, ou être très mal, pour se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoutante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez . Ensuite, une chaise à porteurs vous reconduisait dans votre appartement en location . Mais, à part ces bains , quelle vie mondaine !

Des thermes à l'entrée fort onéreuse mais très plaisants ont ouvert après un délai très long pour cause de malfaçon dans les peintures . Se baigner en plein air avec vue sur la cathédrale dans de l'eau chaude (et sans odeur ) est très plaisant.

Kiki :

Voici un texte de Bath sur le séjour des Polignac que m'a envoyé Clio XVIII :

The Regional Historian: Journal of the Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol, no.18, summer 2008, pp.33-36

A Brush with the Ancien Régime: French Courtiers at Bath in 1787

Trevor Fawcett

The cure – or curiosity – brought a trickle of international gentry to Bath all through the eighteenth century, but until the 1780s rather few of them French. Those cross-Channel visitors who did arrive tended to have business in mind, especially after 1765 when the Bath city freemen, after decades of strenuous opposition to interlopers, finally lost their ancient trading monopolies. Over the next twenty-five years dozens of French nationals – mostly dealers in luxury gods or providers of specialist services – tried their luck at Europe’s fastest growing spa, among them jewellers and toymen, hairdressers and perfumers, milliners, staymakers, dentists, language teachers and dancing masters. Some, finding the milieu congenial, settled. Others relied on seasonal visits. Either way Bath offered rich pickings. The city’s political loyalties might be ostentatiously Hanoverian, but in matters of fashion, especially women’s, it was still Paris that dictated. And on a wider front, too, French culture and language had status value. French tutors found ready employment; the circulating libraries stocked foreign authors; and Antoine Le Texier, well known in London for his French play-readings, performed to appreciative - and presumably francophone - audiences on his repeated visits to Bath from the 1780s onwards.

About the same period, as diplomatic relations defrosted in the aftermath of the American War, the number of overseas visitors listed among the spa arrivals, French included, began to increase. The French ambassador himself, Adhémar de Montfalcon, paid a health visit in April 1785 and was back again in 1786. The same year the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, Marie Antoinette’s brother, caused rather more of a stir when he and his entourage stopped two nights at the York House, Bath’s top hotel. The Anglo-French trade treaty signed in September 1786 not only boosted the displays of French cambrics, wines and candles in the shops, it probably accounted for another small influx of French notables during an unusually brilliant autumn and winter season. Certainly the treaty was assumed by the Bath Chronicle to have brought to England, and then to Bath, a particularly distinguished French party the following spring – the Polignacs and Vaudreuils no less, intimates and favourites of Marie Antoinette for the past twelve years. They arrived in May 1787 accompanied by the French and Spanish ambassadors and also Prince Rezzonico, one of Archduke Ferdinand’s entourage from the previous year. It was evidently no casual visit. Two large lodging houses on North Parade had been hired in advance to serve as the party’s base for well over a month while they enjoyed the spa diversions, called on nearby country houses, and by report dispensed louis d’ors in liberal quantities. Such an unprecedented stay by foreign aristocracy set tongues wagging. Might the motive not be the commercial treaty after all, but the fact that the Polignacs were temporarily out of favour with the French Queen for siding with the recently dismissed minister of finance Calonne, whom she had always disliked and opposed? Or was their own explanation, offered to the Marquis Lansdowne during an outing to Bowood, not perfectly plausible – that they had simply come for the cure? Or were they actually serving Marie Antoinette in some way?

The Archduke Ferdinand’s visit in September 1786 had followed his earlier stay at Versailles at the height of the ‘diamond necklace’ scandal - an affair that did Marie Antoinette so much damage, innocent in this case though she was. The plot was almost farcical. A fabulous necklace had been sold by the court jeweller to the gullible cardinal de Rohan, the late French ambassador in Vienna, anxious to ingratiate himself with the Queen after long being out of favour. Rohan had been tricked into believing that the Queen coveted the necklace, and would pay for it, by a certain Jeanne de la Motte, self-styled comtesse de Valois, who fed him forged letters and arranged a nocturnal meeting with a prostitute feigning to be the Queen. Wanting payment for the necklace, the jeweller unwittingly brought the plot to light, but at Rohan’s subsequent trial before the Paris Parlement in May 1786 he and his associate, the mysterious comte de Cagliostro, were acquitted and only Jeanne de la Motte was sentenced to flogging, branding, and imprisonment in the Salpêtrière. The outcome of the trial, the outpouring of pamphlets, the charges and counter-charges, the public emotions stirred up by all the scurrilous, prurient innuendo, fatally undermined the Queen’s already profligate reputation, and the affair was still festering when the Polignac party came to Bath. Indeed there were fresh complications. Jeanne de la Motte’s husband, having fled to Britain, had been selling off jewels from the necklace and negotiating with Versailles, via the ambassador Adhémar, over his threat to incriminate the Queen still further. In London he associated with other malcontents, among them the exiled Cagliostro whose own best-selling account, The Queen of France’s Necklace, had been available at one Bath bookshop since as early as April 1786. Meanwhile the Polignacs’ ally (but Marie Antoinette’s adversary), Charles Alexandre Calonne, had been dismissed from his key government post as finance minister. Privy to many Court secrets and ready to pen his own self-justification, the Requête au Roi, he too soon turned up in London and eventually in Bath.

With alarm bells ringing at Versailles about the possibility of more revelations, true or not, the Polignac contingent set out for England in early May 1787, ostensibly on a health trip but probably too in the hope of buying silence from their dangerous compatriots in exile. Although the party travelled first to London, their ultimate destination of Bath was well enough known beforehand to William Eden, Britain’s trade negotiator in France, who guessed that ‘the novelty of the [Bath] scene will amuse them while the novelty exists, but they will grow tired’. He noted, however, that they were all fond of gambling, and Bath could well provide for that. Eden regarded the expedition as mainly for pleasure and assumed they would ‘all be chiefly in the Duchess of Devonshire’s society’, knowing the long-standing friendship between the Devonshires and Polignacs which had indeed almost persuaded the duchesse de Polignac to Bath, a favourite haunt of the Devonshires, the year before.

Reaching London on 6 May they met up at once with their old protégé Adhémar and attended the ambassador’s grand assembly the same evening. Two days later, having used the Duchess of Devonshire’s box at the opera, they attended her supper and ball, and on 12 May set out for Bath. En route they spent a night at Stowe and possibly also at Blenheim. Certainly Diane comtesse de Polignac halted at Blenheim, along with Spanish ambassador, these joining the main party at Bath some days later. This brought the company, excluding servants, up to twelve - the duc and duchesse (Yolande) de Polignac, their headstrong sister-in-law Diane de Polignac, their daughter and son-in-law (duc de Guiche), the comte, vicomte and vicomtesse de Vaudreuil, and the diplomatic quartet of Adhémar, two Spaniards (the earl of Polentinos and chevalier Colmenares ), and prince Rezzonico, there presumably to represent Habsburg interests in the French Queen’s affairs. As Eden had predicted, their chief hosts at Bath seem to have been the Devonshires, in whose company they graced the pleasure gardens one evening, though it was Adhémar who escorted them (with the Bishop of Winchester) to view the apothecary William Sole’s botanic garden on the outskirts of town. Details of their movements are otherwise scanty, apart from the already mentioned excursion to Bowood and another to Stourhead and Salisbury. Any negotiations that might have taken place with La Motte remain undocumented – but there is other evidence.

In June 1787 Jeanne de la Motte escaped from the Salpêtrière prison so mysteriously that it seemed only government collusion could explain it. Contemporary diplomatic letters went further. The ‘escape’, it was claimed, was the direct fruit of the Polignac-Vaudreuil jaunt to Bath, where the comte de la Motte had stipulated, in addition to his wife’s release, a price of 4000 louis d’or for handing over a libellous memoir and correspondence supposedly exchanged between cardinal de Rohan and the Queen herself – a price so much higher than expected that the Polignacs had been obliged to dispatch a courier to Versailles to hurry extra funds to England, hence the unexpected long sojourn at Bath and the relieved welcome the duchesse de Polignac received on her return to court with the incendiary documents.

The Polignac-Vaudreuil party, though not the Devonshires, had finally quitted Bath on 16 June and were back at Versailles in about ten days. Their joyous reception soon turned sour. By July the Devonshires were being informed that the duchesse de Polignac had been supplanted by the former favourite (and superintendant of the Queen’s household), the princesse de Lamballe. Perhaps more to the point was the dawning realisation that the mission to prevent unsavoury revelations being broadcast from England had failed. While the potentially damaging letters had been retrieved, the double-dealing comte de la Motte, it was said, had withheld legally attested copies. What was beyond doubt was that the comte would soon be reunited in England with his wife, who also had a tale to tell.

Within days, therefore, a fresh pre-emptive mission was planned, this time headed by the reliable princesse de Lamballe who briskly left for London with her suite in early July. Her rather public and ceremonious stay in England cannot have settled matters, however, for a second, more private visit took place two months later - by which time Jeanne de la Motte and the ex-minister Calonne were both in London and, furthermore, in mutual contact. Thinly disguised under the title ‘comtesse d’Amboise’, the princesse de Lamballe landed at Southampton on 19 September 1787 and reached Bath, again ‘with a numerous retinue’, on the 21st, having called at Lord Palmerston’s Romsey seat en route. The conjecture abroad was that her rendezvous at Bath was with Calonne in person – and Calonne surely must already have known Bath when he chose it, eight months later, as the place for his marriage to his wealthy mistress, Mme d’Harvelay. The presence of the Austrian diplomat, prince Reuss, among the princesse’s advisors lends credence to the view that Calonne was in a position to implicate Marie Antoinette over secret financial transactions with Vienna. In fact his manuscript, copies of which the princesse apparently took back to Versailles, was silent on such matters. Indeed, desperate to regain royal favour, Calonne bent all his efforts over the next few years into shielding the Queen from criticism, becoming embroiled in blackmailing the La Motte couple in the process, as he periodically lamented in his letters to the duchesse de Polignac. Ultimately he failed and Jeanne de la Motte’s notoriously self-serving Mémoires appeared with some noise in late 1788.

The visits paid to Bath by high-standing French emissaries and key foreign ambassadors at this time points to special diplomatic and court concerns on the eve of the French Revolution. Precisely what was transacted there remains speculative, though efforts at damage limitation on behalf of the French Queen seem to have been at the heart of it. If so, the missions largely failed. The wounding publications were not halted and her reputation crumbled further. Moreover, from Bath’s point of view this brush with the Ancien Régime turned out to be merely a prelude. The courtiers had been and gone. Next came the Revolution and with it the many fugitive émigrés who found sanctuary at Bath over the next two decades and more.

Tous en choeur :

Merci, merci, chère Clio !!! :n,,;::::!!!: :n,,;::::!!!: :n,,;::::!!!:

Clio :

Redde caesarea quod caesaris et à Trévor ce qui appartient à Trevor .

Kiki :

C'est palpitant ! Mais, ce n'est pas forcément à prendre au pied de la lettre dans tous les détails, puisque notamment, la Reine est largement incriminée et passe pour avoir organisé l'évasion de la Motte ! C'est du pur délire !!! C'est admettre qu'elle a trempé dans l'affaire du Collier !

On y voit combien les Polignac et les Devonshire étaient liés, et Mme de Lamballe repasser la Manche à la rescousse, les Polignac n'ayant pas entièrement réussi dans leur mission pour contrer la publications des mémoires de la Motte ... Que fabrique Calonne dans tout cela ???

.......................................... FIN DE CE BOUTURAGE !

.........................

.

Dernière édition par Mme de Sabran le Lun 25 Jan 2016, 12:16, édité 1 fois

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55511

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Sait-on en quoi consistait prendre les eaux à l'époque?

Doit-on imaginer Mesdames de Polignac et Lamballe enduites de boue d'argile? :

Bien à vous.

Doit-on imaginer Mesdames de Polignac et Lamballe enduites de boue d'argile? :

Bien à vous.

Invité- Invité

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Oui ! comme tu dis ! : se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoûtante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez n'est pas follement tentant !

se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoûtante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez n'est pas follement tentant !

J'ai connu ça à Budapest dans les termes du XVIIème vraiment magnifiques, mais pouah ! quel bouillon de culture !

Il faut vraiment être motivé .

se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoûtante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez n'est pas follement tentant !

se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoûtante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez n'est pas follement tentant ! J'ai connu ça à Budapest dans les termes du XVIIème vraiment magnifiques, mais pouah ! quel bouillon de culture !

Il faut vraiment être motivé .

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55511

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Comtesse Diane- Messages : 7397

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : TOURAINE

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Dans une version du film "Northanger abbey" , on voit ces dames et ces messieurs faire trempette dans le bain romain ; cela ne donne pas envie d'en faire autant . D'autant que les piscines modernes de Bath sont +++ (le droit d'entréeMme de Sabran a écrit:Oui ! comme tu dis ! :se baigner dans de l'eau peu ragoûtante, vêtu de brun , avec une écuelle remplie d'une sorte de pot pourri sous le nez n'est pas follement tentant !

J'ai connu ça à Budapest dans les termes du XVIIème vraiment magnifiques, mais pouah ! quel bouillon de culture !

Il faut vraiment être motivé .

Bain historique modernisé , the cross bath

Avant

maintenant (on peut le privatiser , un de mes rêves...)

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Nous avions vu quelques jolies scènes du film The Duchess tournées à Bath :

Ce site présente d'ailleurs les lieux et les nombreux films tournées dans cette ville : http://visitbath.co.uk/things-to-do/activities/on-location-film-trail

Ce site présente d'ailleurs les lieux et les nombreux films tournées dans cette ville : http://visitbath.co.uk/things-to-do/activities/on-location-film-trail

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Par cette dernière image du film, je m'aperçois que j'ai devant mon ordinateur même une carte de ce lieu (tirée d'ailleurs du film: j'en reconnais deux voitures  ) que m'a envoyée notre amie Clio boudoi30

) que m'a envoyée notre amie Clio boudoi30

Bien à vous.

Bien à vous.

Invité- Invité

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Jane Austen, de constitution fragile comme Mesdames Princesse de Lamballe et Duchesse de Polignac, s'adonnait aussi aux eaux de Bath, il paraît même que malgré l'aspect ragoûtant de l'eau, ces bains de boue sont très agréables, beaucoup de vertus pour certaines maladies. Et, et et..... comme je suis TRÈS curieuse (surtout pour l'Angleterre pour laquelle j'ai un certain faible), peut-être qu'un jour.... Ce serait amusant de se rendre sur les lieux où ces Dames se sont baignées. La ville de Bath semble magnifique avec une architecture qui me rappelle un peu la ville de Versailles.

Mais, il me semble que nous avons cela aussi en France, notamment dans les environs de Biarritz.

Mais, il me semble que nous avons cela aussi en France, notamment dans les environs de Biarritz.

Trianon- Messages : 3305

Date d'inscription : 22/12/2013

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Ce ne sont pas des bains de boue mais d'eau chaude et les analyses modernes concluent à aucun effet thérapeutiques .

Trianon, Bath est une ville magique, unique en son genre .Pour ma part, pas de ressemblance avec Versailles. Allez-y

Trianon, Bath est une ville magique, unique en son genre .Pour ma part, pas de ressemblance avec Versailles. Allez-y

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

CLIOXVIII a écrit:Pour ma part, pas de ressemblance avec Versailles. Allez-y

A part peut-être les grandes écuries, extérieurement parlant, j'entends ?

Bien à vous.

Invité- Invité

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

CLIOXVIII a écrit:Ce ne sont pas des bains de boue mais d'eau chaude et les analyses modernes concluent à aucun effet thérapeutiques .

Trianon, Bath est une ville magique, unique en son genre .Pour ma part, pas de ressemblance avec Versailles. Allez-y

C'est une ville magique boudoi30 ! Ah, chère amie vous me tentez beaucoup.

L'Angleterre : toujours à la pointe de la modernité et si intimement liée avec le passé. J'adore cette dualité.

Trianon- Messages : 3305

Date d'inscription : 22/12/2013

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

.

1787

De son côté, l'auteur de la Correspondance Secrète publie que Mme de Polignac est partie pour l'Angleterre avec sa famille. M. de Vaudreuil l'a suivie quelques jours après .

Les Polignac restèrent deux mois en Angleterre dont ils passèrent six semaines à Bath mais revinrent précipitamment à Versailles : la petite princesse Sophie venait de mourir .

1787

De son côté, l'auteur de la Correspondance Secrète publie que Mme de Polignac est partie pour l'Angleterre avec sa famille. M. de Vaudreuil l'a suivie quelques jours après .

Les Polignac restèrent deux mois en Angleterre dont ils passèrent six semaines à Bath mais revinrent précipitamment à Versailles : la petite princesse Sophie venait de mourir .

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55511

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55511

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Le Royal Crescent de Bath a été construit entre 1767 et 1774 par l architecte John Wood the elder (l aine ) , les immeubles sont de style palladien avec 114 colonnes , des sash window (fenêtres à guillotine) , des georgian interior shutter ( volet intérieur georgien) , le dernier étage des balustres cachent les lucarnes et une partie des toits en ardoises du Pays de Galles , à l'arrière les façades changent d'une maison à l'autre , des jardins sont présents derrière les maisons , en face se trouve le Royal Victoria Park

nico baku 60- Messages : 26

Date d'inscription : 01/03/2020

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Re: Mesdames de Lamballe et de Polignac, aux eaux de Bath

Merci, Nico Baku !

nico baku 60 a écrit:Le Royal Crescent de Bath a été construit entre 1767 et 1774 par l architecte John Wood the elder (l aine ) , les immeubles sont de style palladien avec 114 colonnes , des sash window (fenêtres à guillotine) , des georgian interior shutter ( volet intérieur georgien) , le dernier étage des balustres cachent les lucarnes et une partie des toits en ardoises du Pays de Galles

Tel que l'ont connu mesdames de Polignac et de Lamballe , promenade obligée qu'elles goûtèrent, à n'en pas douter, maintes fois .

nico baku 60 a écrit:à l'arrière les façades changent d'une maison à l'autre , des jardins sont présents derrière les maisons , en face se trouve le Royal Victoria Park

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55511

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» Les appartements de la princesse de Lamballe et de la duchesse de Polignac au Petit Trianon

» Les Grandes Eaux de Versailles

» Le Hameau de la Reine, à Genval les Eaux

» Versailles, Les Grandes Eaux nocturnes

» VICHY, « Reine des villes d'eaux »

» Les Grandes Eaux de Versailles

» Le Hameau de la Reine, à Genval les Eaux

» Versailles, Les Grandes Eaux nocturnes

» VICHY, « Reine des villes d'eaux »

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La France et le Monde au XVIIIe siècle :: Histoire et événements ailleurs dans le monde

Page 1 sur 1

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum