Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

3 participants

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La France et le Monde au XVIIIe siècle :: Histoire et événements ailleurs dans le monde

Page 1 sur 1

Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Suite à l'intervention de Dominique Poulain dans notre sujet (plus principalement consacré à la mode) :

Série "The Empresses in the Palace" (Legend of Zhen Huan) - Les atours de l'aristocratie chinoise au XVIIIe siècle

Série "The Empresses in the Palace" (Legend of Zhen Huan) - Les atours de l'aristocratie chinoise au XVIIIe siècle

J'ouvre ici cet autre sujet pour revenir sur cette question des impératrices, épouses, et concubines impériales sous la dynastie Qing (1644 - 1912).

J'ouvre ici cet autre sujet pour revenir sur cette question des impératrices, épouses, et concubines impériales sous la dynastie Qing (1644 - 1912).

Scène of "Ruyi's Royal Love in the Palace." (87 episodes)

The first Empress (played by Dong Jie), Empress Dowager (played by Vivian Wu), Emperor Qianlong (played by Wallace Huo)

Image : VCG Photo

Je vous propose donc, à suivre, deux articles intéressants.

En anglais, courage ! Ils ne sont pas si compliqués à lire ; ou utilisez les traducteurs du net...

1) Le premier texte, illustré, présente le fonctionnement du "harem" impérial et comment été effectuée la sélection des "concubines" et épouses de l'empereur.

2) Le second fut rédigé à l'occasion d'une exposition passée, sis au Smithsonian American Art Museum, et intitulée : Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644–1912.

Il présente plus spécifiquement le statut et le rôle des impératrices et impératrices douairières.

Dominique Poulin a écrit:Ne nous y trompons pas et nous ne serons pas trompés : les monarchies d'Orient et d'extrême-Orient assujetissaient la beauté et la grâce des femmes dans les harems, les univers clos, récepteurs de toutes les ambitions, de toutes les intrigues et des pires desseins. La multiplicité des épouses, des subtilités des rangs, le nombre effrayant des concubines exacerbaient encore davantage les luttes d'influence et donc du pouvoir pour approcher le souverain, double objet de la puissance convoitée et redoutée de l'Etat.

La splendeur des palais, des costumes, l'éclat scintillant des cours n'était que la vitrine indispensable mais à double miroir du pouvoir absolu.

Scène of "Ruyi's Royal Love in the Palace." (87 episodes)

The first Empress (played by Dong Jie), Empress Dowager (played by Vivian Wu), Emperor Qianlong (played by Wallace Huo)

Image : VCG Photo

Je vous propose donc, à suivre, deux articles intéressants.

En anglais, courage ! Ils ne sont pas si compliqués à lire ; ou utilisez les traducteurs du net...

1) Le premier texte, illustré, présente le fonctionnement du "harem" impérial et comment été effectuée la sélection des "concubines" et épouses de l'empereur.

2) Le second fut rédigé à l'occasion d'une exposition passée, sis au Smithsonian American Art Museum, et intitulée : Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644–1912.

Il présente plus spécifiquement le statut et le rôle des impératrices et impératrices douairières.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

LIFE INSIDE THE FORBIDDEN CITY : HOW WOMEN WERE SELECTED FOR SERVICE

The inner court was composed of three major groups of women: concubines, palace servants, and the royal princesses

For Forbidden City concubines in imperial China, beauty was more of a curse than a blessing

All women living in the Forbidden City were carefully sequestered in the imperial quarters deep inside the palace. They were restricted to the inner court and forbidden from venturing out of the northern section.

Most women in the Forbidden City were employed as maids and servants, but there was also a select group of concubines whose task was to bear children for the emperor – as many as he could father.

Those who gave birth to male offspring were elevated to imperial consorts, with the empress at the top of the pecking order.

Concubines who gave birth to male offspring were elevated to imperial consorts, with the empress at the top of the pecking order.

Image : South China Morning Post

Women were selected as xiunu (elegant females) for the court as early as the Jin dynasty (265-420 AD) and the selection criteria ranged from emperor to emperor. In the Ming dynasty, for example, no household was exempt from the selection.

According to statutes, all young unmarried women went through xiunu selection process. Only girls who were married or with certified physical disabilities or deformities were exempt.

But the Qing Emperor Shunzhi (1638-61) began to exclude most of the Han population by limiting selection to “Eight Banners” families, who were mainly Manchurian and Mongolian. (Eight Banners was a Manchurian administrative and military framework.)

The Board of Revenue sent notices to officials in the capital and provincial garrisons to enlist the help of clan heads. The banner officials then submitted a list of all available females to the commanders’ headquarters in Beijing and to the Board of Revenue.

Requirements for selection

During the Qing dynasty, girls were brought on the appointed day to the Shenwu (Martial Spirit) Gate of the Forbidden City for inspection. They would be accompanied by their parents, or nearest relatives, together with their clan heads and local officials.

Concubines had to be beautiful enough to satisfy the emperor – and his parents.

Image : South China Morning Post

Social background was no barrier and many emperors chose concubines from the general public. The empress was one exception – she was always selected from the family of a high-ranking official.

Fewer than a hundred of the candidates would be selected to spend several nights with women who specialised in training and managing maids. Candidates’ bodies were inspected for skin infections, body hair, body odour and other things.

The finalists were initiated into forms of acceptable behaviour and how to speak, gesture and walk. They also learned arts such as painting, reading, writing, chess and dancing.

Finally, the stand-out candidates spent several days serving as maids to the emperor’s mother, taking care of her daily needs. They underwent further inspections while sleeping by the mother’s side to root out any bad nocturnal habits, such as snoring, emitting odours or talking or walking in their sleep.

The outstanding 50

Ming Emperor Tianqi, who in 1621 sent eunuchs across the country to handpick 5,000 young women, from whom he would select a wife.

Image : South China Morning Post

In 1621, Ming Emperor Tianqi sent eunuchs across the country to handpick 5,000 young women aged 13 to 16, from whom he would select a wife.

On the second day, the eunuchs intensively examined the women’s bodies and evaluated their voices and manner. This slimmed down the field by another 2,000.

The third day was spent observing their feet, hands and grace of movement. Another 1,000 were eliminated. The remaining 1,000 underwent gynaecological examinations, dismissing another 700 from the process.

The remaining 300 were then housed in the palace where they underwent a month-long series of tests of intelligence, merit, temperament and moral character.

The top 50 candidates were subject to further examinations and interviews about mathematics, literature and art, and ranked accordingly.

Only a few of those who made it through the process would be noticed by the emperor and win his favour.

Image : South China Morning Post

The three favourites would receive the highest ranking for imperial concubines.

Only a few of those who made it through this rigorous process would be noticed by the emperor and win his favour. Most would spend their lives in loneliness and, unsurprisingly, jealousy was rife. Beauty was more of a curse than a blessing in China during this period of history.

Activities

Naturally, concubines were strictly forbidden from having sex with anyone other than the emperor.

Most of their activities were overseen and monitored by eunuchs, who wielded great power in the palace. Concubines were required to bathe and be examined by a court doctor before the emperor visited their bed chamber.

With hundreds, sometimes thousands, of concubines at the emperor’s disposal, any lady the emperor graced with a visit would be subject to jealous rivalries. Concubines had their own rooms and would fill their days applying make-up, sewing, practising various arts and socialising with other concubines.

Many of them spent their entire lives in the palace without any contact with the emperor.

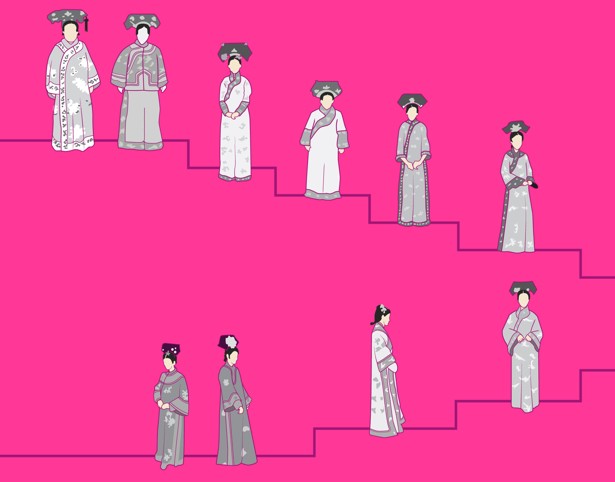

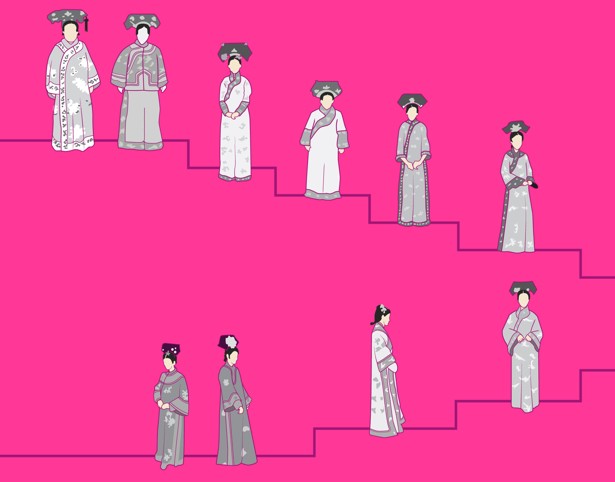

Hierarchy

In the Qing dynasty harem system, the ranking remained consistent but the number of consorts and concubines varied under different emperors.

In the Qing dynasty harem system, the ranking remained consistent but the number of consorts and concubines varied under different emperors.

Image : South China Morning Post

On the same level were the empress (Huanghou), the emperor’s principal wife, and the empress dowager, a title given to the mother, or widow, of an emperor. The dowager lived in the reigns of at least two subsequent emperors.

One step down in rank was the imperial noble consort (Huang Guifei), who ranked second to the empress. Only one consort in the harem could hold this title.

Below her were the imperial consorts (Guifei). The imperial harem had two women with this title.

Following them were the consorts (Fei). Four women in the imperial harem held this title.

Next were the imperial concubines (Pin). There were six women in the imperial harem with this title.

The harem also had an unlimited number of attendants. These three ranks of women – first-class, second-class (higher) and second-class (lower) female attendants – did not have their own palaces and lived communally instead.

The empress, or Huanghou, was the emperor's principal wife.

Image : South China Morning Post

Polygamy

Polygamy was common practice in feudal China, although only upper- and wealthy middle-class men could afford to take several wives. It was seen as an affirmation of male potency, and the presence of many women was taken to indicate a man’s virility.

The emphasis was on procreation and the continuity of the father’s family name. Confucianism emphasised the ability of a man to manage a family as part of his personal growth in daxue (great learning). In the case of the emperor, guaranteeing a successor to the throne was of paramount importance.

The four principles of polygamy in feudal China were:

1. The strict distinction between main wife and concubines

The main wife was superior to all other wives. She was responsible for submitting to the higher principles of polygamy and to mentor the other wives in harmonious behaviour for the greater good.

2. Women must not be jealous

Women, especially the main wife, had to rise above their earthly emotions. The belief that they were living for a higher purpose presumably helped displace feelings of bitterness, jealousy and rivalry.

3. Attachment could radically destabilise polygamy

The husband should not have a favourite, nor should any of the wives monopolise the man. Love had to be distributed evenly among the wives, which effectively meant that passionate attachment was not acceptable.

4. Polygamy could only survive by observing a strict hierarchy

Each dynasty had its own set of titles and ranks for the imperial wives. The empress ranked at the top, with more wives filling successive echelons below her. Most wives occupied the lower echelons. Hierarchy was determined at specific times, such as when a new wife joined the imperial family and was assigned a rank.

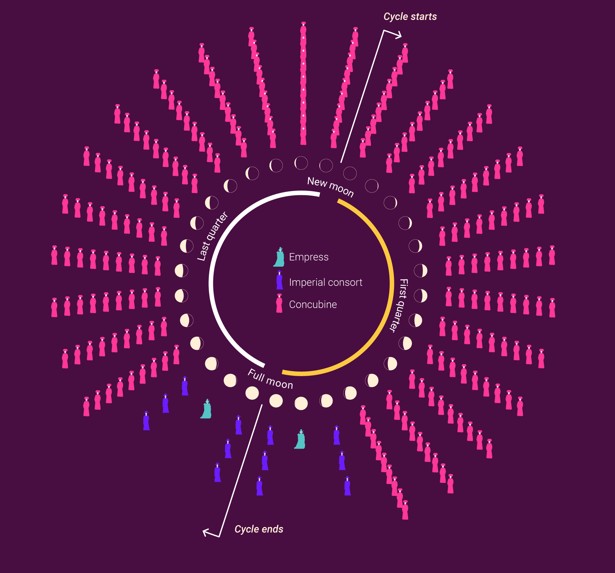

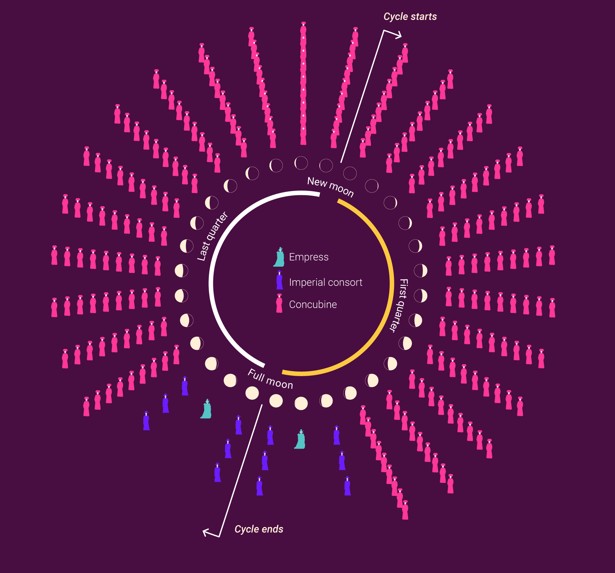

Emperor’s sexual rotation

It was believed that organising the emperor’s sex life was essential to maintaining the well-being of the entire Chinese empire. The Chinese calendars of the 10th century were not used to keep track of time but rather to keep the emperor’s sex schedule in check.

The rotation of concubines sleeping with the emperor was kept to a regimented order. Secretaries were employed to record the emperor’s sex life with brushes dipped in imperial vermilion.

The empress and other wives slept with the emperor around the time of the full moon because it was believed children of strong virtue would be conceived on those nights.

Image : South China Morning Post

Moon cycle

In China, and some other Asian countries, age is determined from the moment of conception, not the moment of birth. The Imperial Chinese believed that women were most likely to conceive during the full moon, when the Yin, or female influence, was strong enough to match the Yang, or male force, of the emperor.

The empress and other wives slept with the emperor around the time of the full moon because it was believed children of strong virtue would be conceived on those nights. The lower-ranking concubines were tasked with nourishing the emperor’s Yang with their Yin, sleeping with him around the time of the new moon.

Palace servants - The Qing Palace Maids

Maids were female servants in the palace. They were ranked according to their families’ social position and they would only be recruited from the Eight Banners families that were mainly Manchurians and Mongolians.

They were selected when they reached the age of 13. Their role was to attend to the daily needs of the empress, imperial consorts and concubines. They could not leave their ladies’ sides, day or night, seven days a week. The maid-in-waiting held the highest rank.

The number of maids assigned to high-ranking women varied

Image : South China Morning Post

(...)

Suite (nurses et princesses), informations complémentaires de ce dossier consultables ici :

Suite (nurses et princesses), informations complémentaires de ce dossier consultables ici :

Life inside the Forbidden City : How Women Were Selected for Service

Life inside the Forbidden City : How Women Were Selected for Service

* Texte de : Marcelo Duhalde ; en collaboration avec Pablo Robles et Darren Long

* Extrait de : Life inside the Forbidden City : How Women Were Selected for Service

* Source : South China Morning Post

The inner court was composed of three major groups of women: concubines, palace servants, and the royal princesses

For Forbidden City concubines in imperial China, beauty was more of a curse than a blessing

All women living in the Forbidden City were carefully sequestered in the imperial quarters deep inside the palace. They were restricted to the inner court and forbidden from venturing out of the northern section.

Most women in the Forbidden City were employed as maids and servants, but there was also a select group of concubines whose task was to bear children for the emperor – as many as he could father.

Those who gave birth to male offspring were elevated to imperial consorts, with the empress at the top of the pecking order.

Concubines who gave birth to male offspring were elevated to imperial consorts, with the empress at the top of the pecking order.

Image : South China Morning Post

Women were selected as xiunu (elegant females) for the court as early as the Jin dynasty (265-420 AD) and the selection criteria ranged from emperor to emperor. In the Ming dynasty, for example, no household was exempt from the selection.

According to statutes, all young unmarried women went through xiunu selection process. Only girls who were married or with certified physical disabilities or deformities were exempt.

But the Qing Emperor Shunzhi (1638-61) began to exclude most of the Han population by limiting selection to “Eight Banners” families, who were mainly Manchurian and Mongolian. (Eight Banners was a Manchurian administrative and military framework.)

The Board of Revenue sent notices to officials in the capital and provincial garrisons to enlist the help of clan heads. The banner officials then submitted a list of all available females to the commanders’ headquarters in Beijing and to the Board of Revenue.

Requirements for selection

During the Qing dynasty, girls were brought on the appointed day to the Shenwu (Martial Spirit) Gate of the Forbidden City for inspection. They would be accompanied by their parents, or nearest relatives, together with their clan heads and local officials.

Concubines had to be beautiful enough to satisfy the emperor – and his parents.

Image : South China Morning Post

Social background was no barrier and many emperors chose concubines from the general public. The empress was one exception – she was always selected from the family of a high-ranking official.

Fewer than a hundred of the candidates would be selected to spend several nights with women who specialised in training and managing maids. Candidates’ bodies were inspected for skin infections, body hair, body odour and other things.

The finalists were initiated into forms of acceptable behaviour and how to speak, gesture and walk. They also learned arts such as painting, reading, writing, chess and dancing.

Finally, the stand-out candidates spent several days serving as maids to the emperor’s mother, taking care of her daily needs. They underwent further inspections while sleeping by the mother’s side to root out any bad nocturnal habits, such as snoring, emitting odours or talking or walking in their sleep.

The outstanding 50

Ming Emperor Tianqi, who in 1621 sent eunuchs across the country to handpick 5,000 young women, from whom he would select a wife.

Image : South China Morning Post

In 1621, Ming Emperor Tianqi sent eunuchs across the country to handpick 5,000 young women aged 13 to 16, from whom he would select a wife.

On the second day, the eunuchs intensively examined the women’s bodies and evaluated their voices and manner. This slimmed down the field by another 2,000.

The third day was spent observing their feet, hands and grace of movement. Another 1,000 were eliminated. The remaining 1,000 underwent gynaecological examinations, dismissing another 700 from the process.

The remaining 300 were then housed in the palace where they underwent a month-long series of tests of intelligence, merit, temperament and moral character.

The top 50 candidates were subject to further examinations and interviews about mathematics, literature and art, and ranked accordingly.

Only a few of those who made it through the process would be noticed by the emperor and win his favour.

Image : South China Morning Post

The three favourites would receive the highest ranking for imperial concubines.

Only a few of those who made it through this rigorous process would be noticed by the emperor and win his favour. Most would spend their lives in loneliness and, unsurprisingly, jealousy was rife. Beauty was more of a curse than a blessing in China during this period of history.

Activities

Naturally, concubines were strictly forbidden from having sex with anyone other than the emperor.

Most of their activities were overseen and monitored by eunuchs, who wielded great power in the palace. Concubines were required to bathe and be examined by a court doctor before the emperor visited their bed chamber.

With hundreds, sometimes thousands, of concubines at the emperor’s disposal, any lady the emperor graced with a visit would be subject to jealous rivalries. Concubines had their own rooms and would fill their days applying make-up, sewing, practising various arts and socialising with other concubines.

Many of them spent their entire lives in the palace without any contact with the emperor.

Hierarchy

In the Qing dynasty harem system, the ranking remained consistent but the number of consorts and concubines varied under different emperors.

In the Qing dynasty harem system, the ranking remained consistent but the number of consorts and concubines varied under different emperors.

Image : South China Morning Post

On the same level were the empress (Huanghou), the emperor’s principal wife, and the empress dowager, a title given to the mother, or widow, of an emperor. The dowager lived in the reigns of at least two subsequent emperors.

One step down in rank was the imperial noble consort (Huang Guifei), who ranked second to the empress. Only one consort in the harem could hold this title.

Below her were the imperial consorts (Guifei). The imperial harem had two women with this title.

Following them were the consorts (Fei). Four women in the imperial harem held this title.

Next were the imperial concubines (Pin). There were six women in the imperial harem with this title.

The harem also had an unlimited number of attendants. These three ranks of women – first-class, second-class (higher) and second-class (lower) female attendants – did not have their own palaces and lived communally instead.

The empress, or Huanghou, was the emperor's principal wife.

Image : South China Morning Post

Polygamy

Polygamy was common practice in feudal China, although only upper- and wealthy middle-class men could afford to take several wives. It was seen as an affirmation of male potency, and the presence of many women was taken to indicate a man’s virility.

The emphasis was on procreation and the continuity of the father’s family name. Confucianism emphasised the ability of a man to manage a family as part of his personal growth in daxue (great learning). In the case of the emperor, guaranteeing a successor to the throne was of paramount importance.

The four principles of polygamy in feudal China were:

1. The strict distinction between main wife and concubines

The main wife was superior to all other wives. She was responsible for submitting to the higher principles of polygamy and to mentor the other wives in harmonious behaviour for the greater good.

2. Women must not be jealous

Women, especially the main wife, had to rise above their earthly emotions. The belief that they were living for a higher purpose presumably helped displace feelings of bitterness, jealousy and rivalry.

3. Attachment could radically destabilise polygamy

The husband should not have a favourite, nor should any of the wives monopolise the man. Love had to be distributed evenly among the wives, which effectively meant that passionate attachment was not acceptable.

4. Polygamy could only survive by observing a strict hierarchy

Each dynasty had its own set of titles and ranks for the imperial wives. The empress ranked at the top, with more wives filling successive echelons below her. Most wives occupied the lower echelons. Hierarchy was determined at specific times, such as when a new wife joined the imperial family and was assigned a rank.

Emperor’s sexual rotation

It was believed that organising the emperor’s sex life was essential to maintaining the well-being of the entire Chinese empire. The Chinese calendars of the 10th century were not used to keep track of time but rather to keep the emperor’s sex schedule in check.

The rotation of concubines sleeping with the emperor was kept to a regimented order. Secretaries were employed to record the emperor’s sex life with brushes dipped in imperial vermilion.

The empress and other wives slept with the emperor around the time of the full moon because it was believed children of strong virtue would be conceived on those nights.

Image : South China Morning Post

Moon cycle

In China, and some other Asian countries, age is determined from the moment of conception, not the moment of birth. The Imperial Chinese believed that women were most likely to conceive during the full moon, when the Yin, or female influence, was strong enough to match the Yang, or male force, of the emperor.

The empress and other wives slept with the emperor around the time of the full moon because it was believed children of strong virtue would be conceived on those nights. The lower-ranking concubines were tasked with nourishing the emperor’s Yang with their Yin, sleeping with him around the time of the new moon.

Palace servants - The Qing Palace Maids

Maids were female servants in the palace. They were ranked according to their families’ social position and they would only be recruited from the Eight Banners families that were mainly Manchurians and Mongolians.

They were selected when they reached the age of 13. Their role was to attend to the daily needs of the empress, imperial consorts and concubines. They could not leave their ladies’ sides, day or night, seven days a week. The maid-in-waiting held the highest rank.

The number of maids assigned to high-ranking women varied

Image : South China Morning Post

(...)

* Texte de : Marcelo Duhalde ; en collaboration avec Pablo Robles et Darren Long

* Extrait de : Life inside the Forbidden City : How Women Were Selected for Service

* Source : South China Morning Post

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

EMPRESSES IN THE QING DYNASTY, 1644 - 1912

When an empress or any rank of consort (imperial wife) was chosen to enter the palace, she pledged total allegiance to the imperial family and severed ties to her natal family. In effect, she became imperial property.

At the same time, she was also highly regarded and could help shape the history of the Qing dynasty court.

Explored here are the myriad experiences of empresses, from marriage, state duty, physical activity, and motherhood to festivities, fashionable living, and religious devotion.

Empresses were surrounded by sumptuous objects that befitted their esteemed status at court, their responsibilities, and their pleasures.

Supplied by the imperial household, these objects were considered to be court property, not personal belongings. When an empress died, palace staff returned many of the objects to the storehouse for possible reassignment to another woman of similar status. Ultimately, this practice helped preserve a rich variety of material that today provides valuable insight into the lives of Qing empresses.

Image caption : Map of the Forbidden City. Main Living Quarters of and Sites visited by Noble Women

Based on illustration by Chiu-Kwong-Chiu, Design and Cultural Studies Workshop, Hong Kong, published in Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912.

Image : Smithsonian - National Museum of Asian Art

Path into the Qing Palace

The emperor and imperial princes had multiple consorts simultaneously, but there could be only one empress at a time : the emperor’s primary wife.

Every three years the Qing court required families of the conquering elite—descendants of the Manchus and allies who subjugated China in 1644—to present their daughters, at about the age of thirteen , as candidates for the imperial harem. Girls from Han Chinese families, the empire’s largest population group, were essentially excluded.

, as candidates for the imperial harem. Girls from Han Chinese families, the empire’s largest population group, were essentially excluded.

Portraits of Emperor Qianlong, the Empress, and Eleven Imperial Consorts

By Giuseppe Castiglione and other artists.

Ink, silk drawing, from 1736 to 1770

Image : Cleveland Museum of Art - Art History Project

Description

This extrordinary scroll was painted over the 34 year reign of Emperor Qianlong. Giuseppe Castiglione began the scroll, painting the emperor, empress, and his first consort ; the scroll was completed by other artists from the emperor's court.

It is read from right to left, beginning with the emperor himself, followed by the empress, then his eleven 'consorts.' It's a strangely familial portrait, with a quiet tenderness in the faces — and it's clear that Qianlong felt a sense of peace and pride in the decades-long artwork, titling it "Mind Picture of a Well-Governed and Tranquil Reign." From the seals on the scroll, we know that in his old age, after stepping down from the throne, Qianlong opened his scroll to meditate on his life and loves.

Detail of Portraits of Emperor Qianlong and Empress XiaoXian

The emperor and his mother, the empress dowager, selected several consorts at a time, judging each according to her physical beauty, health, and family background as well as her potential to create strategic alliances.

A chosen wife was assigned a rank from one (the empress) down to eight. This position determined her status in the palace and her allotment of goods and servants. Others were appointed to serve five-year terms as ladies-in-waiting. If they happened to catch the emperor’s eye, they might be promoted into the harem. Otherwise, they returned to their family after their service.

Out of more than two dozen Qing empresses, only four entered the court with the status of empress. Other empresses were first chosen as a lower-rank consort, or even as a lady-in-waiting, and later—if the position was vacant—received the title of empress, usually after giving birth to a son.

Position at Court

Whether as the emperor’s mother or as his wife, an empress was honored as the “mother of the state” and served as a role model for women throughout the empire. She was not allowed to rule directly—Empress Dowager Cixi is a notable exception—but she assumed ritual duties, could offer counsel to the emperor, and played a role in educating young princes.

As a whole, Qing empresses did not bind their feet, which enabled them to travel. Some even rode horses. Mobility aided their understanding of the world outside the Forbidden City. Many shared the emperor’s concerns about state affairs.

Several initiated or increased the popularity of Tibetan Buddhism among the imperial family, and a few even advised underage emperors. The influence of empresses was largely indirect but nonetheless significant. Their magnificent court attire served as an outward reflection of their elevated status at court.

Noble Consort, late Empress Xiaoyichun (1727 – 1775)

She was an Imperial Noble Consort of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and also the mother of the Qianlong Emperor's successor, the Jiaqing Emperor.

She was posthumously honoured as an Empress because her son became Emperor, even though she never held the rank of Empress while she was living.

Source et infos complémenaires : Empress Xiaoyichun (Peoplepill.com)

Motherhood as Duty

Giving birth to sons was the primary duty of an imperial consort, and she was expected to properly raise and help educate her young boys. Male offspring were also key to her upward mobility and influence in the palace.

Rules for succession, established in the eighteenth century, were based on a male heir’s personal merit rather than on his birth order or his mother’s status at court. Every son born to an empress or any other imperial consort had an equal chance to reign over the Qing empire. The emperor’s choice for a successor was not revealed until after his death.

The possibility that any favored son could become the next emperor was a source of jealously and competition among many consorts. The empress’s high status at court granted her the position of being the nominal mother of all of the emperor’s children, whether or not she was the birth mother.

Empress Xiaoxian.

Ignatius Sichelbarth (Ai Qimeng, 1708–1780) and Yi Lantai (act. ca. 1748–86) and possibly Wang Ruxue (act. 18th century).

China, Qianlong period, 1777, with repainting possibly 19th century.

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk.

Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Sturgis Hinds, 1956, E33619

Celebrating Motherhood

Filial piety, a core social value in China, emphasizes devotion and care for parents and elder family members. An emperor’s dutiful attention toward his mother, the empress dowager, gave her considerable status and influence in the imperial court. Filial acts included writing Buddhist sutras, creating paintings dedicated to her, and staging elaborate birthday celebrations to honor her.

One significant role of the empress dowager was to help select wives for her son.

Some imperial mothers shaped dynastic history in another way : if her son was too young to rule when he assumed the throne, she could act as his advisor. A close relationship between an imperial mother and her son was thought to reflect the harmonious society that Qing emperors credited to their rule.

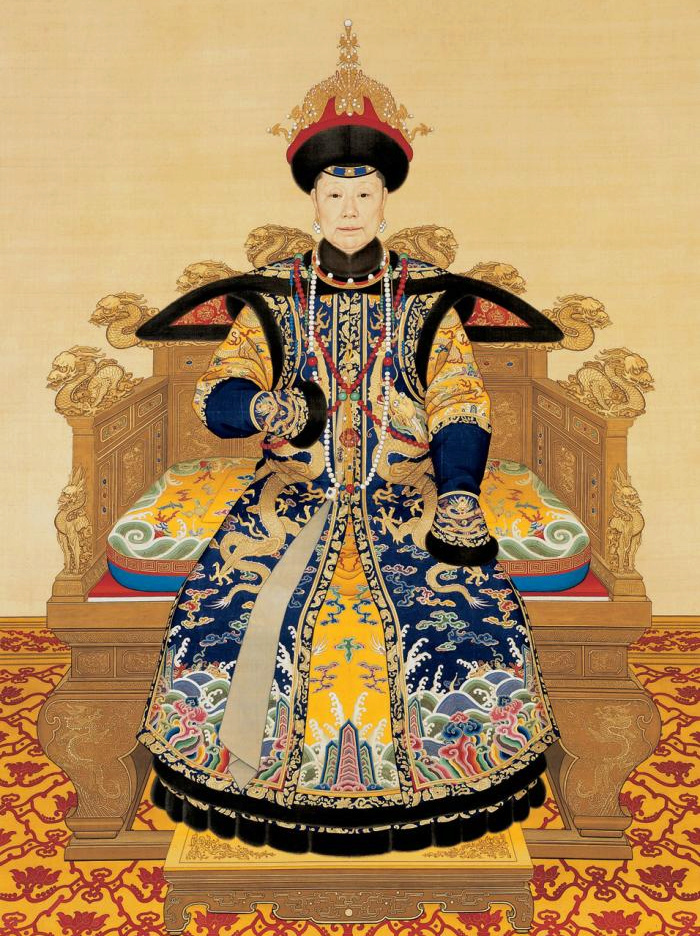

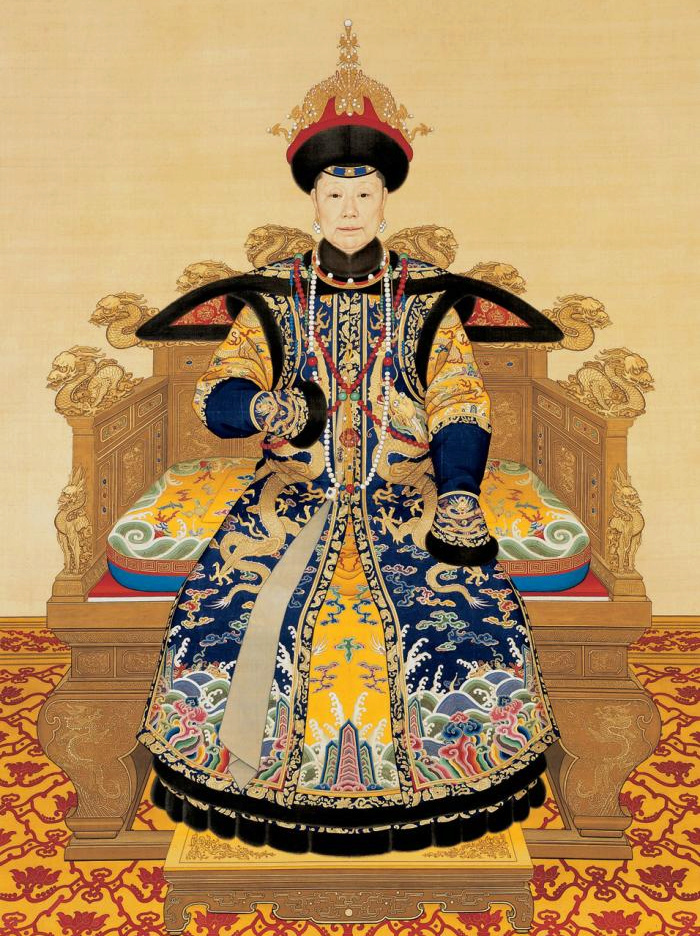

Xiaosheng, Empress Dowager (1691—1771), the mother of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736—95), on her sixtieth birthday

By anonymous court artists

1751 (Qianlong period)

Hanging scroll, colour on silk. 230.5×141.3 cm. The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Image : Commons Wikimedia

A Full and Active Life

Within the strict confines of imperial court strictures, Qing empresses engaged in rewarding lives. Beyond court duties, such as raising children or presiding over state rituals to promote silk production, they indulged in the pleasurable diversions of traveling, celebrating seasonal festivals, watching and even commissioning operas, and being pampered with special beauty regimes.

They also derived great satisfaction in their religious devotion. At the end of the dynasty, Empress Dowager Cixi blurred the realms of sacred and secular by theatrically presenting herself as a Buddhist deity.

Imagine attentive maids perfuming the rooms of an empress, helping her pick stunning jewelry and flowers to create an elaborate hairstyle, or finding a book or artwork to enjoy.

The cosmopolitan tastes of many empresses led them to collect and, in the case of at least one, even create works of art. Their privileged lifestyle served as the subject of court paintings that the emperor and the women themselves appreciated.

La " concubine " ou dit portrait de Hoifa-Nara, " the Step Empress ", seconde impératrice consort de l'empereur Qianlong

Attribué à Jean-Denis Attiret

XVIIIe siècle

Image : musée de Dole / Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole

Jean-Denis Attiret (né à Dole en 1702, mort à Pékin en 1768) est jésuite et part évangéliser la Chine au 18e siècle. Il devient le peintre de la cour royale de Chine. C'est là qu'il rencontre la princesse Ulanara. Concubine, elle devient impératrice au décès de la première épouse.

Il est devenu le peintre Wang Tche-tch'eng et maîtrise totalement le symbolisme du costume chinois et des codes de la cour impériale.

Voir notre sujet : Le portrait interdit, film de Charles de Meaux

Virtues of Wifely Appearance

Ancient texts from roughly the time of Confucius—some 2,500 years ago—identify four virtues for women : being faithful in marriage, practicing proper speech, projecting a “wifely appearance,” and diligently overseeing domestic work.

Empresses and other consorts were expected to achieve an acceptable demeanor that balanced decorum and appeal. Their daily routines of dressing and adding accessories of jewelry were considered expressions of conjugal devotion. It was, after all, a wife’s duty to please the emperor and attract his attention in the hopes of bearing his son.

To enhance their complexions, imperial women of high status used massage tools to tone their faces and applied fine powders and rouge. They used exquisite hairdressing tools and combs to create elaborate coiffures.

Women completed their look with colorful hairpins, earrings, bracelets, and rings made of luxury materials, such as jade, gold, coral, pearls, and kingfisher feathers.

Ladies of the Palace

Photographed by Frank Carpenter and his daughter Frances.

The picture shows the rich detail of court fashion during the last years of the Manchu Qing dynasty

Image : Missionary Photos Early 1900s life China Years Imperial Rule (Daily Mail)

Worshipping as an Empress

Qing empresses participated in, and even helped shape, many spiritual traditions practiced at the imperial court, including shamanism and Buddhism. By promoting Tibetan Buddhism, they opened an important avenue for the Manchu rulers to engage with Tibetans and to bond with their potential rivals, the Mongols.

Devotional activities also provided many empresses, particularly widows, with spiritual consolation, opportunities to pray for blessings for their family and the state, and hope for a rewarding afterlife.

The imperial court commissioned magnificent buildings, scriptures, sculptures, and liturgical equipment for the religious observations of empresses and to commemorate them in death.

Navigating Politics and Diplomacy

Though tradition declared “women shall not rule,” ambitious empresses found ways to exercise influence in the realm of politics. Empress Dowager Cixi even wielded direct power, including in the international arena.

These exalted women gained special access to the heart of power through their relationships with certain male relatives and particularly with their husband or son, the emperor. Prominence and authority also depended on their own talent, personality, and historical circumstances.

Empress Dowager Cixi took bold advantage of changing times to meet with outsiders, including the wife of the American ambassador and other foreigners. Like male rulers, she used art to proclaim her supremacy and to fashion images of herself as an erudite and benevolent leader.

Detail – The Empress Dowager Cixi

China, Qing Dynasty 1903-1904

Glass plate negative / Imperial-size gelatin silver print photograph with hand-applied color.

Courtesy of Blair House, The President’s Guest House, United States Department of State

* Source texte et infos complémentaires : Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art - Empresses of China's Forbidden City, 1644 - 1912

When an empress or any rank of consort (imperial wife) was chosen to enter the palace, she pledged total allegiance to the imperial family and severed ties to her natal family. In effect, she became imperial property.

At the same time, she was also highly regarded and could help shape the history of the Qing dynasty court.

Explored here are the myriad experiences of empresses, from marriage, state duty, physical activity, and motherhood to festivities, fashionable living, and religious devotion.

Empresses were surrounded by sumptuous objects that befitted their esteemed status at court, their responsibilities, and their pleasures.

Supplied by the imperial household, these objects were considered to be court property, not personal belongings. When an empress died, palace staff returned many of the objects to the storehouse for possible reassignment to another woman of similar status. Ultimately, this practice helped preserve a rich variety of material that today provides valuable insight into the lives of Qing empresses.

Image caption : Map of the Forbidden City. Main Living Quarters of and Sites visited by Noble Women

Based on illustration by Chiu-Kwong-Chiu, Design and Cultural Studies Workshop, Hong Kong, published in Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912.

Image : Smithsonian - National Museum of Asian Art

Path into the Qing Palace

The emperor and imperial princes had multiple consorts simultaneously, but there could be only one empress at a time : the emperor’s primary wife.

Every three years the Qing court required families of the conquering elite—descendants of the Manchus and allies who subjugated China in 1644—to present their daughters, at about the age of thirteen

Portraits of Emperor Qianlong, the Empress, and Eleven Imperial Consorts

By Giuseppe Castiglione and other artists.

Ink, silk drawing, from 1736 to 1770

Image : Cleveland Museum of Art - Art History Project

Description

This extrordinary scroll was painted over the 34 year reign of Emperor Qianlong. Giuseppe Castiglione began the scroll, painting the emperor, empress, and his first consort ; the scroll was completed by other artists from the emperor's court.

It is read from right to left, beginning with the emperor himself, followed by the empress, then his eleven 'consorts.' It's a strangely familial portrait, with a quiet tenderness in the faces — and it's clear that Qianlong felt a sense of peace and pride in the decades-long artwork, titling it "Mind Picture of a Well-Governed and Tranquil Reign." From the seals on the scroll, we know that in his old age, after stepping down from the throne, Qianlong opened his scroll to meditate on his life and loves.

Detail of Portraits of Emperor Qianlong and Empress XiaoXian

The emperor and his mother, the empress dowager, selected several consorts at a time, judging each according to her physical beauty, health, and family background as well as her potential to create strategic alliances.

A chosen wife was assigned a rank from one (the empress) down to eight. This position determined her status in the palace and her allotment of goods and servants. Others were appointed to serve five-year terms as ladies-in-waiting. If they happened to catch the emperor’s eye, they might be promoted into the harem. Otherwise, they returned to their family after their service.

Out of more than two dozen Qing empresses, only four entered the court with the status of empress. Other empresses were first chosen as a lower-rank consort, or even as a lady-in-waiting, and later—if the position was vacant—received the title of empress, usually after giving birth to a son.

Position at Court

Whether as the emperor’s mother or as his wife, an empress was honored as the “mother of the state” and served as a role model for women throughout the empire. She was not allowed to rule directly—Empress Dowager Cixi is a notable exception—but she assumed ritual duties, could offer counsel to the emperor, and played a role in educating young princes.

As a whole, Qing empresses did not bind their feet, which enabled them to travel. Some even rode horses. Mobility aided their understanding of the world outside the Forbidden City. Many shared the emperor’s concerns about state affairs.

Several initiated or increased the popularity of Tibetan Buddhism among the imperial family, and a few even advised underage emperors. The influence of empresses was largely indirect but nonetheless significant. Their magnificent court attire served as an outward reflection of their elevated status at court.

Noble Consort, late Empress Xiaoyichun (1727 – 1775)

She was an Imperial Noble Consort of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and also the mother of the Qianlong Emperor's successor, the Jiaqing Emperor.

She was posthumously honoured as an Empress because her son became Emperor, even though she never held the rank of Empress while she was living.

Source et infos complémenaires : Empress Xiaoyichun (Peoplepill.com)

Motherhood as Duty

Giving birth to sons was the primary duty of an imperial consort, and she was expected to properly raise and help educate her young boys. Male offspring were also key to her upward mobility and influence in the palace.

Rules for succession, established in the eighteenth century, were based on a male heir’s personal merit rather than on his birth order or his mother’s status at court. Every son born to an empress or any other imperial consort had an equal chance to reign over the Qing empire. The emperor’s choice for a successor was not revealed until after his death.

The possibility that any favored son could become the next emperor was a source of jealously and competition among many consorts. The empress’s high status at court granted her the position of being the nominal mother of all of the emperor’s children, whether or not she was the birth mother.

Empress Xiaoxian.

Ignatius Sichelbarth (Ai Qimeng, 1708–1780) and Yi Lantai (act. ca. 1748–86) and possibly Wang Ruxue (act. 18th century).

China, Qianlong period, 1777, with repainting possibly 19th century.

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk.

Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Sturgis Hinds, 1956, E33619

Celebrating Motherhood

Filial piety, a core social value in China, emphasizes devotion and care for parents and elder family members. An emperor’s dutiful attention toward his mother, the empress dowager, gave her considerable status and influence in the imperial court. Filial acts included writing Buddhist sutras, creating paintings dedicated to her, and staging elaborate birthday celebrations to honor her.

One significant role of the empress dowager was to help select wives for her son.

Some imperial mothers shaped dynastic history in another way : if her son was too young to rule when he assumed the throne, she could act as his advisor. A close relationship between an imperial mother and her son was thought to reflect the harmonious society that Qing emperors credited to their rule.

Xiaosheng, Empress Dowager (1691—1771), the mother of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736—95), on her sixtieth birthday

By anonymous court artists

1751 (Qianlong period)

Hanging scroll, colour on silk. 230.5×141.3 cm. The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Image : Commons Wikimedia

A Full and Active Life

Within the strict confines of imperial court strictures, Qing empresses engaged in rewarding lives. Beyond court duties, such as raising children or presiding over state rituals to promote silk production, they indulged in the pleasurable diversions of traveling, celebrating seasonal festivals, watching and even commissioning operas, and being pampered with special beauty regimes.

They also derived great satisfaction in their religious devotion. At the end of the dynasty, Empress Dowager Cixi blurred the realms of sacred and secular by theatrically presenting herself as a Buddhist deity.

Imagine attentive maids perfuming the rooms of an empress, helping her pick stunning jewelry and flowers to create an elaborate hairstyle, or finding a book or artwork to enjoy.

The cosmopolitan tastes of many empresses led them to collect and, in the case of at least one, even create works of art. Their privileged lifestyle served as the subject of court paintings that the emperor and the women themselves appreciated.

La " concubine " ou dit portrait de Hoifa-Nara, " the Step Empress ", seconde impératrice consort de l'empereur Qianlong

Attribué à Jean-Denis Attiret

XVIIIe siècle

Image : musée de Dole / Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole

Jean-Denis Attiret (né à Dole en 1702, mort à Pékin en 1768) est jésuite et part évangéliser la Chine au 18e siècle. Il devient le peintre de la cour royale de Chine. C'est là qu'il rencontre la princesse Ulanara. Concubine, elle devient impératrice au décès de la première épouse.

Il est devenu le peintre Wang Tche-tch'eng et maîtrise totalement le symbolisme du costume chinois et des codes de la cour impériale.

Voir notre sujet : Le portrait interdit, film de Charles de Meaux

Virtues of Wifely Appearance

Ancient texts from roughly the time of Confucius—some 2,500 years ago—identify four virtues for women : being faithful in marriage, practicing proper speech, projecting a “wifely appearance,” and diligently overseeing domestic work.

Empresses and other consorts were expected to achieve an acceptable demeanor that balanced decorum and appeal. Their daily routines of dressing and adding accessories of jewelry were considered expressions of conjugal devotion. It was, after all, a wife’s duty to please the emperor and attract his attention in the hopes of bearing his son.

To enhance their complexions, imperial women of high status used massage tools to tone their faces and applied fine powders and rouge. They used exquisite hairdressing tools and combs to create elaborate coiffures.

Women completed their look with colorful hairpins, earrings, bracelets, and rings made of luxury materials, such as jade, gold, coral, pearls, and kingfisher feathers.

Ladies of the Palace

Photographed by Frank Carpenter and his daughter Frances.

The picture shows the rich detail of court fashion during the last years of the Manchu Qing dynasty

Image : Missionary Photos Early 1900s life China Years Imperial Rule (Daily Mail)

Worshipping as an Empress

Qing empresses participated in, and even helped shape, many spiritual traditions practiced at the imperial court, including shamanism and Buddhism. By promoting Tibetan Buddhism, they opened an important avenue for the Manchu rulers to engage with Tibetans and to bond with their potential rivals, the Mongols.

Devotional activities also provided many empresses, particularly widows, with spiritual consolation, opportunities to pray for blessings for their family and the state, and hope for a rewarding afterlife.

The imperial court commissioned magnificent buildings, scriptures, sculptures, and liturgical equipment for the religious observations of empresses and to commemorate them in death.

Navigating Politics and Diplomacy

Though tradition declared “women shall not rule,” ambitious empresses found ways to exercise influence in the realm of politics. Empress Dowager Cixi even wielded direct power, including in the international arena.

These exalted women gained special access to the heart of power through their relationships with certain male relatives and particularly with their husband or son, the emperor. Prominence and authority also depended on their own talent, personality, and historical circumstances.

Empress Dowager Cixi took bold advantage of changing times to meet with outsiders, including the wife of the American ambassador and other foreigners. Like male rulers, she used art to proclaim her supremacy and to fashion images of herself as an erudite and benevolent leader.

Detail – The Empress Dowager Cixi

China, Qing Dynasty 1903-1904

Glass plate negative / Imperial-size gelatin silver print photograph with hand-applied color.

Courtesy of Blair House, The President’s Guest House, United States Department of State

* Source texte et infos complémentaires : Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art - Empresses of China's Forbidden City, 1644 - 1912

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Ma foi, malgré la somptuosité des costumes et la beauté envoûtante de la Cité Interdite, je crois que j'aurais préféré être la dernière des paysannes, pliée en deux dans la rizière pour enfoncer de petites pousses dans la glaise, plutôt que l'une de ces hiératiques épouses ou concubines de l'empereur, ni plus ni moins prisonnières de leur rang ...

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Ah oui ? Pas moi !

A choisir, entre être prisonnière de mon rang ou d'une vie misérable, je préfèrerais plutôt " l'enfer, mais doré ".

Au moins ces femmes ne crevaient pas de faim.

D'ailleurs je ne pense pas que ces " élues " le vivaient toutes comme une malédiction, au contraire.

A choisir, entre être prisonnière de mon rang ou d'une vie misérable, je préfèrerais plutôt " l'enfer, mais doré ".

Au moins ces femmes ne crevaient pas de faim.

D'ailleurs je ne pense pas que ces " élues " le vivaient toutes comme une malédiction, au contraire.

Dernière édition par La nuit, la neige le Mer 01 Jan 2020, 19:14, édité 1 fois

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

La nuit, la neige a écrit:

Au moins ces femmes ne crevaient pas de faim.

Non, elles étaient ( pour certaines ) bien proprement assassinées ...

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Bah ! Dans ta rizière tu n'aurais certainement pas fait de vieux os non plus...

Et quelle vie, fût-elle longue !

Et quelle vie, fût-elle longue !

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

I agree. Plutôt mourir dans la soie que les pieds dans la rizière

Marie-Jeanne- Messages : 1497

Date d'inscription : 16/09/2018

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Non, non !!

C'est peut-être toi, dans ta rizière, qui aurait eu les pieds trempés du soir au matin Et recroquevillés !

A coup sûr, Marie-Jeanne (et moi ) aurions glissé nos grands pieds dans des chaussons de soie...

) aurions glissé nos grands pieds dans des chaussons de soie...

Cette pratique " traditionnelle " ne concernait pas les femmes Mandchous, donc de la dynastie des Quing (dont il est ici question), mais celles des Hans (et peut-être d'autres "populations ethniques" de l'empire chinois, je ne sais pas).

Ce que nous précisions déjà dans notre sujet : L'impératrice douairière Cixi

Cette impératrice ayant d'ailleurs souhaité mettre fin à cette tradition par un décret d'interdiction dans tout l'Empire (certes, en 1902 seulement).

Or, dans les textes que j'ai cités, il est précisé que, dès le règne de l'empereur Shunzhi (1638-61), furent exclues comme épouses et concubines les femmes appartenant à la population Han.

Seules les jeunes filles appartenant aux familles des "Huit Bannières" (principalement donc des Mandchous et des Mongoles) étaient sélectionnées.

C'est peut-être toi, dans ta rizière, qui aurait eu les pieds trempés du soir au matin Et recroquevillés !

A coup sûr, Marie-Jeanne (et moi

) aurions glissé nos grands pieds dans des chaussons de soie...

) aurions glissé nos grands pieds dans des chaussons de soie...

Cette pratique " traditionnelle " ne concernait pas les femmes Mandchous, donc de la dynastie des Quing (dont il est ici question), mais celles des Hans (et peut-être d'autres "populations ethniques" de l'empire chinois, je ne sais pas).

Ce que nous précisions déjà dans notre sujet : L'impératrice douairière Cixi

Cette impératrice ayant d'ailleurs souhaité mettre fin à cette tradition par un décret d'interdiction dans tout l'Empire (certes, en 1902 seulement).

Or, dans les textes que j'ai cités, il est précisé que, dès le règne de l'empereur Shunzhi (1638-61), furent exclues comme épouses et concubines les femmes appartenant à la population Han.

Seules les jeunes filles appartenant aux familles des "Huit Bannières" (principalement donc des Mandchous et des Mongoles) étaient sélectionnées.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

La nuit, la neige a écrit:Non, non !!

C'est peut-être toi, dans ta rizière, qui aurait eu les pieds trempés du soir au matin Et recroquevillés !

A coup sûr, Marie-Jeanne (et moi) aurions glissé nos grands pieds dans des chaussons de soie...

Ton 45 fillette sans doute, les doigts de pieds en éventail, mais Marie-Jeanne aurait bel et bien titubé sur ses deux petits moignons .

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Mais non. Pourquoi ?

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Eh bien mais je suppose que toutes ces épouses et concubines avaient les pieds bandés. C'était un signe d'élégance indispensable, a fortiori au sein de la Cité Interdite.

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Ah ! Tu n'as pas lu la suite de mon message...

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Oups, pardon !  Cette pratique n'était donc pas entièrement généralisée. Je préfère tout de même ma rizière (

Cette pratique n'était donc pas entièrement généralisée. Je préfère tout de même ma rizière (  ) à la cage dorée de la Cité Interdite. Elle n'est d'ailleurs pas sans me rappeler le harem royal de la Sublime Porte, dont notre ami Calonne nous avait si bien expliqué le fonctionnement très barbare .

) à la cage dorée de la Cité Interdite. Elle n'est d'ailleurs pas sans me rappeler le harem royal de la Sublime Porte, dont notre ami Calonne nous avait si bien expliqué le fonctionnement très barbare .

) à la cage dorée de la Cité Interdite. Elle n'est d'ailleurs pas sans me rappeler le harem royal de la Sublime Porte, dont notre ami Calonne nous avait si bien expliqué le fonctionnement très barbare .

) à la cage dorée de la Cité Interdite. Elle n'est d'ailleurs pas sans me rappeler le harem royal de la Sublime Porte, dont notre ami Calonne nous avait si bien expliqué le fonctionnement très barbare . _________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55497

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

Re: Impératrices, épouses et concubines de l'empereur de Chine (dynastie Qing) dans la Cité Interdite

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18132

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» Expositions : La Chine à Versailles (2014 et 2022) et La Cité Interdite et le Château de Versailles (2024)

» Louis-François-Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, maréchal et duc de Richelieu

» Johann Christian Neuber, orfèvre de la cour de Saxe, et la table de Teschen

» C’est au programme TV

» A Tahiti, la dynastie des Pōmare

» Louis-François-Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, maréchal et duc de Richelieu

» Johann Christian Neuber, orfèvre de la cour de Saxe, et la table de Teschen

» C’est au programme TV

» A Tahiti, la dynastie des Pōmare

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La France et le Monde au XVIIIe siècle :: Histoire et événements ailleurs dans le monde

Page 1 sur 1

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum