Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

+7

La nuit, la neige

Mme de Sabran

Trianon

Olivier

Comtesse Diane

CLIOXVIII

Gouverneur Morris

11 participants

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La famille royale et les contemporains de Marie-Antoinette :: Autres contemporains : les femmes du XVIIIe siècle

Page 5 sur 6

Page 5 sur 6 •  1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Duc d'Ostrogothie a écrit:C’était intéressant en effet . Certainement plus réussi que l’émission sur les “favoris” de Marie-Antoinette.

Tout à fait !

J’ai été surpris d’apprendre que Marie-Antoinette et Marie-Caroline n’étaient pas proches et ne s’écrivaient jamais.

Oui, je me faisais la même remarque. A force d'évoquer leur enfance commune, leurs échanges de cadeaux (pourtant protocolaires), de comparer leur destin et d'évoquer la haine de la reine de Naples pour la Révolution, on se sera sans doute conditionnés nous-mêmes à croire le contraire....

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

La nuit, la neige a écrit:Ah oui ?

Gone with the Wind (1939)

That Hamilton Woman (1941)

Divine Vivian Leigh...

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Merci, les garçons, pour tous ces détails, vous êtes de vrais puits de science !!!

Gouverneur Morris a écrit: A force d'évoquer leur enfance commune, leurs échanges de cadeaux (pourtant protocolaires), de comparer leur destin et d'évoquer la haine de la reine de Naples pour la Révolution, on se sera sans doute conditionnés nous-mêmes à croire le contraire....

Il y a pourtant des témoignages sur leur enfance et ce désir de Marie-Thérèse de les séparer autant que possible, parce qu'elles sont trop accrochées l'une à l'autre à son gré.

Est-ce que je me trompe ?

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Retour dans ce sujet suite à la diffusion, hier soir sur France 3, de l'excellent :

Secrets d'Histoire - Splendeur et déchéance de Lady Hamilton.

Secrets d'Histoire - Splendeur et déchéance de Lady Hamilton.

La Penserosa: a portrait of Lady Emma Hamilton

By Sir Thomas Lawrence, c. 1791-92

Image : The Abercorn Heirloom Settlement Trustees / Bryan F. Rutledge B.A

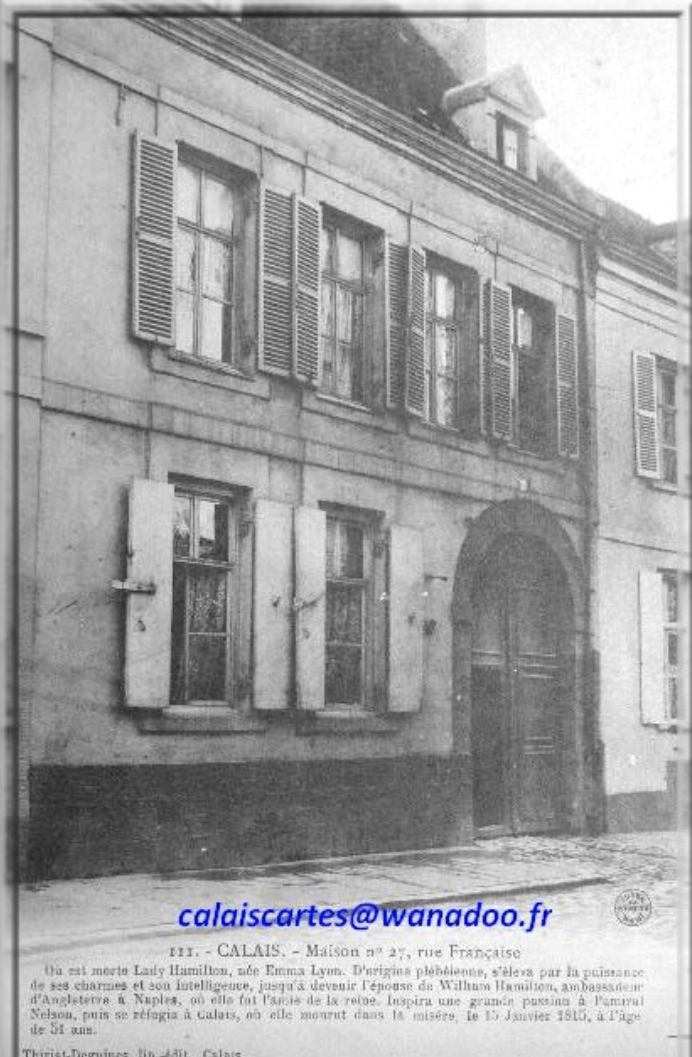

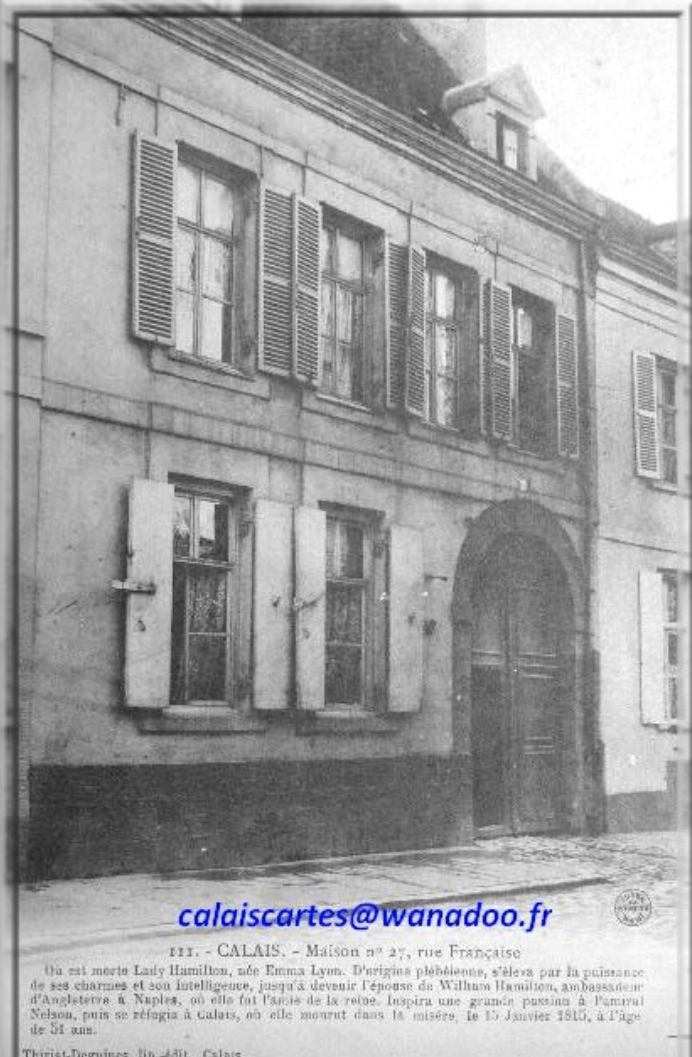

Je reviens sur la fin de vie d'Emma, contrainte de fuir l'Angleterre avec sa fille, pour venir, comble du destin, s'échouer en France, à Calais.

Je reviens sur la fin de vie d'Emma, contrainte de fuir l'Angleterre avec sa fille, pour venir, comble du destin, s'échouer en France, à Calais.

Le site internet de la ville de Calais présente ainsi le monument érigé à sa mémoire :

MONUMENT À LADY HAMILTON

Inauguré le 23 avril 1994, ce monument offert par les membres de l’association britannique Club 1805 commémore la mémoire de Lady HAMILTON.

Images : Calais - Côte d'Opale

Issue d’une famille modeste anglaise, Emma LYON (née en 1765) devient aide-nurse à la mort de son père puis part à Londres pour divers petits emplois. (Petits emplois, c'est mignon... )

)

Ses années avec Charles GREVILLE, descendant « des WARWICK », lui font rencontrer l’oncle de ce dernier, Sir William HAMILTON, ambassadeur de sa majesté à Naples.

A l’initiative de son compagnon, elle part à Naples pour devenir une Lady en tant que maîtresse de l’oncle, contre paiement par ce dernier des dettes de GREVILLE.

Lors de ce séjour, elle comprend qu’elle a été manipulée et épouse en 1791, à Londres, Sir HAMILTON. En 1793, elle rencontre Sir Horatio NELSON, venu à Naples chercher des renforts pour contrer les Français. Cet illustre marin, de retour après la bataille d’Aboukir (Egypte), est accueilli en triomphateur.

Cependant, le héros tombe malade et c’est Emma qui le soigne avec dévouement alors qu’on le juge perdu. Une romance d’amour éclate entre Emma et Horatio, mariés chacun de leur côté.

Images : Calais - Côte d'Opale

De retour à Londres, le trio s’installe et Emma aménage sa propriété à la gloire de son héros. Elle donne naissance à Horatia NELSON le 3 janvier 1801. Mais la mort de Sir HAMILTON en 1803 puis de NELSON en 1805 porte un coup terrible à Emma, annonciateur de sa déchéance.

Elle épuise rapidement l'héritage de Sir William et s’endette profondément.

Malgré le statut de NELSON, héros national, les instructions qu'il laisse au gouvernement pour Emma sont ignorées. De crainte d’être incarcérée pour dettes, elle se réfugie avec sa fille à Calais et meurt d'alcoolisme en 1815, dans une maison, rue Française.

* Source texte : Ville de Calais - Monument à Emma Hamilton

Et voici quelques images de la maison où elle acheva sa vie romanesque, rue Française, aujourd'hui totalement transformée...

Et voici quelques images de la maison où elle acheva sa vie romanesque, rue Française, aujourd'hui totalement transformée...

Image : Google Maps

Image : Calais.fr / Fred Collier

Images : Calais en 1901

La Penserosa: a portrait of Lady Emma Hamilton

By Sir Thomas Lawrence, c. 1791-92

Image : The Abercorn Heirloom Settlement Trustees / Bryan F. Rutledge B.A

Le site internet de la ville de Calais présente ainsi le monument érigé à sa mémoire :

MONUMENT À LADY HAMILTON

Inauguré le 23 avril 1994, ce monument offert par les membres de l’association britannique Club 1805 commémore la mémoire de Lady HAMILTON.

Images : Calais - Côte d'Opale

Issue d’une famille modeste anglaise, Emma LYON (née en 1765) devient aide-nurse à la mort de son père puis part à Londres pour divers petits emplois. (Petits emplois, c'est mignon...

)

)Ses années avec Charles GREVILLE, descendant « des WARWICK », lui font rencontrer l’oncle de ce dernier, Sir William HAMILTON, ambassadeur de sa majesté à Naples.

A l’initiative de son compagnon, elle part à Naples pour devenir une Lady en tant que maîtresse de l’oncle, contre paiement par ce dernier des dettes de GREVILLE.

Lors de ce séjour, elle comprend qu’elle a été manipulée et épouse en 1791, à Londres, Sir HAMILTON. En 1793, elle rencontre Sir Horatio NELSON, venu à Naples chercher des renforts pour contrer les Français. Cet illustre marin, de retour après la bataille d’Aboukir (Egypte), est accueilli en triomphateur.

Cependant, le héros tombe malade et c’est Emma qui le soigne avec dévouement alors qu’on le juge perdu. Une romance d’amour éclate entre Emma et Horatio, mariés chacun de leur côté.

Images : Calais - Côte d'Opale

De retour à Londres, le trio s’installe et Emma aménage sa propriété à la gloire de son héros. Elle donne naissance à Horatia NELSON le 3 janvier 1801. Mais la mort de Sir HAMILTON en 1803 puis de NELSON en 1805 porte un coup terrible à Emma, annonciateur de sa déchéance.

Elle épuise rapidement l'héritage de Sir William et s’endette profondément.

Malgré le statut de NELSON, héros national, les instructions qu'il laisse au gouvernement pour Emma sont ignorées. De crainte d’être incarcérée pour dettes, elle se réfugie avec sa fille à Calais et meurt d'alcoolisme en 1815, dans une maison, rue Française.

* Source texte : Ville de Calais - Monument à Emma Hamilton

Image : Google Maps

Image : Calais.fr / Fred Collier

Images : Calais en 1901

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Oh merci LNLN !

Quel dommage que cette modeste et émouvante maison ait été détruite...

Quel dommage que cette modeste et émouvante maison ait été détruite...

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Merci, cher la nuit, la neige !

Gouverneur Morris a écrit: cette modeste et émouvante maison ...

Oui, il y a loin du lit de rêve dans lequel Emma devait s'endormir à Caserte à ce pauvre grabat que nous montre ta dernière photo ...

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Je reviens avec un extrait des Mémoires de la comtesse de Boigne que nous citions précédemment (page 2 de ce sujet pour la citation complète) qui étrille cette chère Emma...

Mais c'est ce passage qui m'intéresse plus particulièrement :

Dans le documentaire vu hier soir, il est dit qu'Emma rencontre la reine Marie-Caroline après avoir épousé Lord Hamilton en Angleterre (1791), et qu'elle est parvenue à conquérir la confiance de la reine de Naples parce qu'elle lui aurait remis une lettre confiée par Marie-Antoinette lors du retour vers Naples du couple Hamilton.

Dans le documentaire vu hier soir, il est dit qu'Emma rencontre la reine Marie-Caroline après avoir épousé Lord Hamilton en Angleterre (1791), et qu'elle est parvenue à conquérir la confiance de la reine de Naples parce qu'elle lui aurait remis une lettre confiée par Marie-Antoinette lors du retour vers Naples du couple Hamilton.

Nous avions déjà évoqué cette hypothétique lettre, au début de ce sujet, avec la citation suivante de la biographie Wiki consacrée à Emma Hamilton :

Sur le chemin du retour vers Naples, le couple fait halte à Vincennes où il rencontre le roi Louis XVI et la reine Marie-Antoinette, qui sont alors en résidence surveillée. La reine lui confie une lettre destinée à la reine de Naples, sa sœur. C'est ainsi qu'elle devient une amie proche de la reine Marie-Caroline d'Autriche, épouse de Ferdinand Ier de Naples *.

* Source : Natalia Griffon de Pleineville, "Amiral Nelson, la face cachée du héros" dans la Revue Napoléon, no 21, juin 2016, p. 43-55

Nous aimerions bien en savoir plus...

S'il est possible d'admettre que Marie-Antoinette ait consenti à "croiser" l'ambassadeur d'Angleterre à Naples et son épouse, alors de passage en France, aurait-elle confié à cette "aventurière" une lettre destinée à sa soeur ?

Si c'est le cas, il est à supposer que la teneur du courrier devait être fort banale.

Nous avions présenté un mot, attribué à Marie-Antoinette, adressé à son beau-frère, ici :

Nous avions présenté un mot, attribué à Marie-Antoinette, adressé à son beau-frère, ici :

Lettre de Marie-Antoinette à Ferdinand Ier des Deux-Siciles

Lettre de Marie-Antoinette à Ferdinand Ier des Deux-Siciles

Et pour ce qui concerne la correspondance et les écrits de / attribués à Marie-Caroline :

Et pour ce qui concerne la correspondance et les écrits de / attribués à Marie-Caroline :

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à la duchesse de La Trémoïlle (Louise de Châtillon, princesse de Tarente)

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à la duchesse de La Trémoïlle (Louise de Châtillon, princesse de Tarente)

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à la duchesse de Polignac

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à la duchesse de Polignac

Le journal de la reine Marie-Caroline de Naples

Le journal de la reine Marie-Caroline de Naples

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à Charles-Alexandre de Calonne

Lettre de Marie-Caroline à Charles-Alexandre de Calonne

Lettres inédites de Marie-Caroline au marquis de Gallo

Lettres inédites de Marie-Caroline au marquis de Gallo

Oups !Mémoires de la comtesse de Boigne a écrit:

Hors cet instinct pour les arts, rien n'était plus vulgaire et plus commun que lady Hamilton. Lorsqu'elle quittait la tunique antique pour porter le costume ordinaire, elle perdait toute distinction. Sa conversation était dépourvue d'intérêt, même d'intelligence.

Cependant il fallait bien qu'elle eût une sorte de finesse à ajouter à la séduction de son incomparable beauté, car elle a exercé une entière domination sur les personnes qu'elle a eu intérêt à gouverner : son vieux mari d'abord qu'elle a couvert de ridicule, la reine de Naples qu'elle a spoliée et déshonorée, et lord Nelson qui a souillé sa gloire sous l'empire de cette femme, devenue monstrueusement grasse et ayant perdu sa beauté.

Malgré tout ce qu'elle s'était fait donner par lui, par la reine de Naples et par sir William Hamilton, elle a fini par mourir dans la détresse et l'humiliation aussi bien que dans le désordre. C'était, à tout à prendre, une mauvaise femme et une âme basse dans une enveloppe superbe.

Mais c'est ce passage qui m'intéresse plus particulièrement :

Mémoires de la comtesse de Boigne a écrit:

La reine de Naples avait eu beaucoup de peine à consentir à la recevoir. Ma mère avait été employée par sir William à obtenir cette faveur.

(...)

Il est indubitable que les cruelles vengeances exercées à Naples, sous le nom de la Reine et de lord Nelson, ont été provoquées, on peut même dire commandées par lady Hamilton. Elle leur persuadait mutuellement que chacun d'eux les exigeait.

Ma mère en fut d'autant plus désolée qu'elle était fort attachée à la reine Caroline avec laquelle elle est restée en correspondance très suivie, et à qui elle a eu dans la suite de grandes obligations.

Nous avions déjà évoqué cette hypothétique lettre, au début de ce sujet, avec la citation suivante de la biographie Wiki consacrée à Emma Hamilton :

Sur le chemin du retour vers Naples, le couple fait halte à Vincennes où il rencontre le roi Louis XVI et la reine Marie-Antoinette, qui sont alors en résidence surveillée. La reine lui confie une lettre destinée à la reine de Naples, sa sœur. C'est ainsi qu'elle devient une amie proche de la reine Marie-Caroline d'Autriche, épouse de Ferdinand Ier de Naples *.

* Source : Natalia Griffon de Pleineville, "Amiral Nelson, la face cachée du héros" dans la Revue Napoléon, no 21, juin 2016, p. 43-55

Nous aimerions bien en savoir plus...

S'il est possible d'admettre que Marie-Antoinette ait consenti à "croiser" l'ambassadeur d'Angleterre à Naples et son épouse, alors de passage en France, aurait-elle confié à cette "aventurière" une lettre destinée à sa soeur ?

Si c'est le cas, il est à supposer que la teneur du courrier devait être fort banale.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Je ne la sens pas trop, cette histoire de lettre ...

La nuit, la neige a écrit:

Il est indubitable que les cruelles vengeances exercées à Naples, sous le nom de la Reine et de lord Nelson, ont été provoquées, on peut même dire commandées par lady Hamilton. Elle leur persuadait mutuellement que chacun d'eux les exigeait.

... carrément ?!!

Même à supposer que Mme de Boigne en rajoute ( jalousie de femme ? condescendance pour une arriviste ? mépris pour une ancienne prostituée ? ) , Emma semble vraiment avoir une très regrettable part d'ombre.

Du reste, les intervenants ont beaucoup vanté son éblouissante beauté et son intelligence, mais nous n'avons pas entendu grand chose sur ses qualités de coeur .

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Ah mais justement, c’est ce que je dis, on extrapole sur la base de leur enfance commune

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Oui n’oublions pas que derrière sa grande perspicacité sur bien des événements, qui va parfois jusqu’à l’autocritique (Napoléon), Mme de Boigne reste une femme, une femme qui se souviendra toujours être née Osmond qui plus est

Rappelons ainsi qu’elle ne consentit à épouser un riche aventurier que pour sauver sa famille de la misère.

Rappelons ainsi qu’elle ne consentit à épouser un riche aventurier que pour sauver sa famille de la misère.

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Que Mme de Boigne tente "d'épargner" Marie-Caroline comme d'autres ont tenté ainsi d'expliquer ce terrible "faux pas" dans la vie de Nelson est fort possible, mais il n'en reste pas moins que Lady Hamilton fut activement mêlée à cette répression impitoyable. Jusqu'à quel point ? C'est encore à voir.Mme de Sabran a écrit:

Même à supposer que Mme de Boigne en rajoute ( jalousie de femme ? condescendance pour une arriviste ? mépris pour une ancienne prostituée ? ), Emma semble vraiment avoir une très regrettable part d'ombre.

Mais bon, ce n'est guère étonnant, après tout.

Elle était de toutes les manières du côté de Marie-Caroline, folle de rage contre les Français depuis la mort de sa soeur et l'invasion de ses états, et contre les "républicains" napolitains qui l'avaient contrainte de déguerpir de son palais (fuite désastreuse au cours de laquelle elle perd un enfant).

Emma se range du côté de sa "protectrice" : il n'est pas question pour elle de perdre la confiance de la reine.

Peut-être en profita-t-elle aussi pour régler quelques comptes à ceux qui l'avait méprisée ?

Quel coeur ? Dans quel état est-il ?Mme de Sabran a écrit:Du reste, les intervenants ont beaucoup vanté son éblouissante beauté et son intelligence, mais nous n'avons pas entendu grand chose sur ses qualités de coeur .

Je ne voudrais pas être cynique mais elle a bien trop souffert : prostituée adolescente, méprisée par ses premiers amants, contrainte d'abandonner son premier enfant, "vendue" par son premier amour. Crois-tu qu'elle a épousé Lord Hamilton parce qu'elle l'aimait ?

C'est une survivante, dans un monde rude et impitoyable pour une femme de sa condition.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Tu crois que tous les hommes et femmes qui sont maltraités par la vie y perdent leurs âmes ?

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Je parle de Lady Hamilton. C'est une ambitieuse, qui s'est sans doute rendu compte assez vite que ses "qualités de coeur" n'étaient pas ce pourquoi elle est parvenue à tirer son épingle du jeu.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Mais donc, convenons-en, elle a bien obtenu ce qu'elle voulait au bout du compte, dans un premier temps tout du moins : c'est à dire sortir de la misère et de sa condition de pauvre fille du peuple obligée de se vendre .

Loin du fog londonien, elle se prélasse dans les palais de Naples. Elle roule carrosse.

Quand elle devient partie prenante dans la répression atroce exercée par Marie-Caroline ( peut-être même l'instigatrice, selon Mme de Boigne ! ), elle n'a pas encore, pour montrer autant de cruauté ( attention, hein ! si c'est vrai ... ), elle n'a pas encore, disais-je, l'excuse d'être tellement blessée par la vie et retombée dans l'indigence sordide qu'elle connaîtra par la suite .

J'ai bien peur d'être confuse . Est-ce que tu me suis ?!

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Ah ? Tu parlais donc de cet épisode exclusivement ? Eh bien je ne sais pas quoi te répondre...

Force est de constater qu'elle n'aurait pas cherché à convaincre Nelson tout d'abord, puis Marie-Caroline et Ferdinand, de se montrer plus cléments envers les "révolutionnaires" napolitains.

Bien au contraire, apparemment : des témoignages du temps existent.

No mercy !!

Destruction de l'arbre de la liberté à Largo di Palazzo

Guiscard? / Saviero (Xavier) della Gatta? (active 1777-1828)

Huile sur toile, 1799

Collection particulière

Image : Wikipedia

Force est de constater qu'elle n'aurait pas cherché à convaincre Nelson tout d'abord, puis Marie-Caroline et Ferdinand, de se montrer plus cléments envers les "révolutionnaires" napolitains.

Bien au contraire, apparemment : des témoignages du temps existent.

No mercy !!

Destruction de l'arbre de la liberté à Largo di Palazzo

Guiscard? / Saviero (Xavier) della Gatta? (active 1777-1828)

Huile sur toile, 1799

Collection particulière

Image : Wikipedia

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Je reviens sur ce message de l'ami Gouv', initialement posté dans ce sujet : Lits du XVIIIe siècle

Je suis surpris de ton taux de conversion, mais bon, je n'y connais rien, et admettons.

Mais en ce cas, il n'en demeure pas moins que la somme ne paraît pas si extraordinaire pour l'époque.

Mais en ce cas, il n'en demeure pas moins que la somme ne paraît pas si extraordinaire pour l'époque.

Je cite un extrait du livre L'amiral Nelson de Roger Knight :

Hamilton avait signé son testament le 31 mars 1803.

Il laissait son argent et les quelques oeuvres d'art qui lui restaient à Charles Greville, et ses biens immobiliers du Pembrokshire à son parent, le marquis d'Abercorn, à charge pour lui de prélever sur le revenu de ceux-ci une rente annuelle de 800 livres sterling à verser à Emma de son vivant sur lesquels 100 livres devaient être données à la mère d'Emma.

À Nelson, il légua un portrait d'Emma , " un très modeste témoignage de la très grande considération que j'éprouve pour sa Seigneurie, l'homme le plus vertueux, le plus loyal et le plus authentiquement courageux que j'aie jamais rencontré ".

Minto confia à son épouse : " J'ai rencontré Lady Hamilton qui est moins bien lotie que je ne l'imaginais, son douaire étant fixé à 700 livres par an et celui de Mrs Cadogan à 100 livres. Elle m'a dit avoir sollicité une pension auprès de M. Addington ".

Cela représentait moins de la moitié du montant que Nelson avait attribué à Fanny (son épouse, de qui il vivait séparément). Les temps étaient durs pour Emma.

Thomas Masterman Hardy posa une question pertinente, lorsqu'il se demanda : " Je peine à imaginer comment Lady Hamilton parviendra désormais à vivre en compagnie du héros de la bataille d'Aboukir, du moins de manière honorable ".

La somme paraît donc faible aux contemporains ; et qui sait si ce marquis d'Abercorn a respecté cet engagement ? Sans doute pas...

La somme paraît donc faible aux contemporains ; et qui sait si ce marquis d'Abercorn a respecté cet engagement ? Sans doute pas...

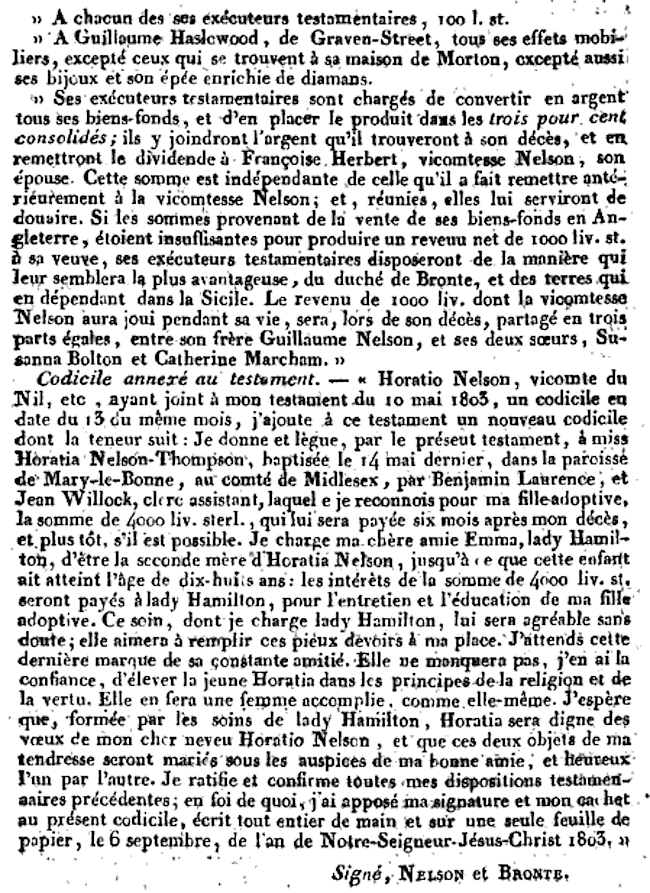

Et voici, la copie d'un extrait du testament de Nelson cette fois-ci :

Et voici, la copie d'un extrait du testament de Nelson cette fois-ci :

Nelson lègue donc seulement à sa fille " adoptive " la somme de 400 livres. Emma Hamilton ne pouvant toucher que les intérêts de ce petit héritage.

Nelson lègue donc seulement à sa fille " adoptive " la somme de 400 livres. Emma Hamilton ne pouvant toucher que les intérêts de ce petit héritage.

Et j'écrivais page 1 de ce sujet :

Et j'écrivais page 1 de ce sujet :

Enfin, peu avant que la bataille de Trafalgar ne s'engage, Nelson écrira un nouveau codicille à son testament (devant deux témoins), laissant Emma comme " legs à mon Roi et à mon pays ", et Horatia " à la bienveillance de mon pays ".

Enfin, peu avant que la bataille de Trafalgar ne s'engage, Nelson écrira un nouveau codicille à son testament (devant deux témoins), laissant Emma comme " legs à mon Roi et à mon pays ", et Horatia " à la bienveillance de mon pays ".

Peine perdue : elle n'aura rien ! Ce qui est assez moche, il faut en convenir.

Ce qui est assez moche, il faut en convenir.

Gouverneur Morris a écrit:

Nous montons donc à 400 livres sterling pour ce lit, ce qui était colossal pour l'époque (l'équivalent-or de 72 000 de nos euros).

Je ne comprends d'ailleurs pas qu'un historien ait pu dire chez Bern, qu'en ne laissant qu'une rente de 400 livres sterlings à Emma, Lord Hamilton ne lui avait pratiquement rien laisséC'est confondre livre sterling et tournois.

Je suis surpris de ton taux de conversion, mais bon, je n'y connais rien, et admettons.

Je cite un extrait du livre L'amiral Nelson de Roger Knight :

Hamilton avait signé son testament le 31 mars 1803.

Il laissait son argent et les quelques oeuvres d'art qui lui restaient à Charles Greville, et ses biens immobiliers du Pembrokshire à son parent, le marquis d'Abercorn, à charge pour lui de prélever sur le revenu de ceux-ci une rente annuelle de 800 livres sterling à verser à Emma de son vivant sur lesquels 100 livres devaient être données à la mère d'Emma.

À Nelson, il légua un portrait d'Emma , " un très modeste témoignage de la très grande considération que j'éprouve pour sa Seigneurie, l'homme le plus vertueux, le plus loyal et le plus authentiquement courageux que j'aie jamais rencontré ".

Minto confia à son épouse : " J'ai rencontré Lady Hamilton qui est moins bien lotie que je ne l'imaginais, son douaire étant fixé à 700 livres par an et celui de Mrs Cadogan à 100 livres. Elle m'a dit avoir sollicité une pension auprès de M. Addington ".

Cela représentait moins de la moitié du montant que Nelson avait attribué à Fanny (son épouse, de qui il vivait séparément). Les temps étaient durs pour Emma.

Thomas Masterman Hardy posa une question pertinente, lorsqu'il se demanda : " Je peine à imaginer comment Lady Hamilton parviendra désormais à vivre en compagnie du héros de la bataille d'Aboukir, du moins de manière honorable ".

La nuit, la neige a écrit:

Après la mort de Nelson en 1805 à la bataille de Trafalgar, Emma ne touche aucun héritage, le frère de Nelson s'étant arrangé pour détruire le codicille la favorisant.

Si Fanny, la femme de Nelson, touchera une partie de l'héritage et Horatia (qui passe alors pour une filleule d'Horatio), touchera une somme modeste, c'est le frère d'Horatio qui est le légataire principal.

Emma se fait passer à cette époque pour la gouvernante de sa fille et ne lui dira jamais qui est sa mère.

Sans héritage ni fortune, continuant pourtant de mener grand train, contrainte de vendre au fur et à mesure ses tableaux, son argenterie, ses meubles précieux, Emma s'endette lourdement en dix ans. Alcoolique, bouffie, souffrant d'une cirrhose du foie, elle est harcelée par ses créanciers.

Sa correspondance entretenue avec Nelson, dont on ne sait si elle fut volée ou vendue par ses soins, est finalement publiée et fait scandale.

Peine perdue : elle n'aura rien !

Ce qui est assez moche, il faut en convenir.

Ce qui est assez moche, il faut en convenir.

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Merci LNLN d'ouvrir cette discussion !

Je me suis basé sur un site de conversion dont les ordres de gradeur sont effectivement différents de ceux que l'on peut trouver sur la fiche Wiki consacrée au Prince-Régent (mais c'est toute la difficulté de cet exercice absurde je l'admets) :

Ce qui fait des 800 livres de pension d'Emma l'équivalent de 106,000 euros par an (contre 144 000 selon le site que j'ai utilisé).

Cela n'est toujours pas trop mal ! Mais insuffisant pour vivre à la Cour sans doute, surtout quand on est le tonneau des danaïdes perosnnifié.

Rappelons à titre de comparaison que le gouvernement anglais versait à Louis XVIII "seulement" 10 fois plus, à savoir 8 000 livres (ce qui était également le montant de la liste civile accordé au cadet des enfants de George III).

Je me suis basé sur un site de conversion dont les ordres de gradeur sont effectivement différents de ceux que l'on peut trouver sur la fiche Wiki consacrée au Prince-Régent (mais c'est toute la difficulté de cet exercice absurde je l'admets) :

Wiki a écrit:The Prince of Wales turned 21 in 1783, and obtained a grant of £60,000 (equivalent to £7,095,000 today[6]) from Parliament and an annual income of £50,000 (equivalent to £5,913,000 today[6])

Ce qui fait des 800 livres de pension d'Emma l'équivalent de 106,000 euros par an (contre 144 000 selon le site que j'ai utilisé).

Cela n'est toujours pas trop mal ! Mais insuffisant pour vivre à la Cour sans doute, surtout quand on est le tonneau des danaïdes perosnnifié.

Rappelons à titre de comparaison que le gouvernement anglais versait à Louis XVIII "seulement" 10 fois plus, à savoir 8 000 livres (ce qui était également le montant de la liste civile accordé au cadet des enfants de George III).

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Merci pour ces informations complémentaires...

Je pense tout de même que nous avons, généralement, un problème pour convertir ces montants avec nos euros et le "coût de la vie" qui va avec.

Interrogations que nous soulevions aussi dans notre sujet : Convertisseur de monnaies d'Ancien Régime

Hamilton était supposé être quasi ruiné à son retour en Angleterre, et nous savons qu'il fut contraint de vendre une très grands partie de sa collection d'antiquités (qui fait la joie du British Museum aujourd'hui).

Or l'un de ses héritiers est supposé verser Emma une part seulement des revenus qu'il tire de biens immobiliers appartenant à feu Hamilton. 100 000 balles de rente par an pour seulement une fraction d'héritage d'un homme prétendument ruiné nous paraît, aujourd'hui, une somme assez confortable !

Fallait-il que cette élite dépense des sommes considérables, chaque mois ?

Car Emma Hamilton ne fréquentait pas la cour. Une fois son époux décédé, elle redevenait " infréquentable " (et sa liaison scandaleuse avec Nelson n'arrangeait rien).

Aussi, ce marquis d'Abercorn (héritier d'Hamilton, en charge d'entretenir Emma et sa mère à la mort de son parent) a-t-il honoré cet engagement ?

L'on peut supposer que non. Ou bien, comme tu le dis, fallait-il qu'Emma soit une sacrée flambeuse ! Ce qui est possible...

Je pense tout de même que nous avons, généralement, un problème pour convertir ces montants avec nos euros et le "coût de la vie" qui va avec.

Interrogations que nous soulevions aussi dans notre sujet : Convertisseur de monnaies d'Ancien Régime

Hamilton était supposé être quasi ruiné à son retour en Angleterre, et nous savons qu'il fut contraint de vendre une très grands partie de sa collection d'antiquités (qui fait la joie du British Museum aujourd'hui).

Or l'un de ses héritiers est supposé verser Emma une part seulement des revenus qu'il tire de biens immobiliers appartenant à feu Hamilton. 100 000 balles de rente par an pour seulement une fraction d'héritage d'un homme prétendument ruiné nous paraît, aujourd'hui, une somme assez confortable !

Fallait-il que cette élite dépense des sommes considérables, chaque mois ?

Car Emma Hamilton ne fréquentait pas la cour. Une fois son époux décédé, elle redevenait " infréquentable " (et sa liaison scandaleuse avec Nelson n'arrangeait rien).

Aussi, ce marquis d'Abercorn (héritier d'Hamilton, en charge d'entretenir Emma et sa mère à la mort de son parent) a-t-il honoré cet engagement ?

L'on peut supposer que non. Ou bien, comme tu le dis, fallait-il qu'Emma soit une sacrée flambeuse ! Ce qui est possible...

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Merci LNLN. Il serait intéressant, au cas particulier, de savoir le taux de change de la livre sterling en tournois à la veille de la Révolution.

Cela nous donnerait plus de références pour évaluer le revenu de l’infortunée courtisane

Cela nous donnerait plus de références pour évaluer le revenu de l’infortunée courtisane

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11798

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Aujourd'hui, au micro de son émission sur Radio Classique, Franck Ferrand nous racontait l'histoire à peine croyable, tant elle est romanesque, de...

Lady Hamilton - Franck Ferrand raconte (Radio Classique)

Lady Hamilton - Franck Ferrand raconte (Radio Classique)

Portrait of Emma Hamilton

By Angelica Kauffmann

c.1791

Black and white chalk, on gray prepared paper

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Portrait of Emma Hamilton

By Angelica Kauffmann

c.1791

Black and white chalk, on gray prepared paper

Image : The Metropolitan Museum of Art

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Ce dessin est si beau !

Je te remercie vivement pour le lien vers cette émission .

Je te remercie vivement pour le lien vers cette émission .

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55517

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Tu n'apprendras rien de nouveau, mais bon, pour passer le temps...Mme de Sabran a écrit:Je te remercie vivement pour le lien vers cette émission .

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

C'est un très beau et original portrait d'Emma qui sera prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères...

Je cite des extraits de l'interminable note au catalogue

:

:

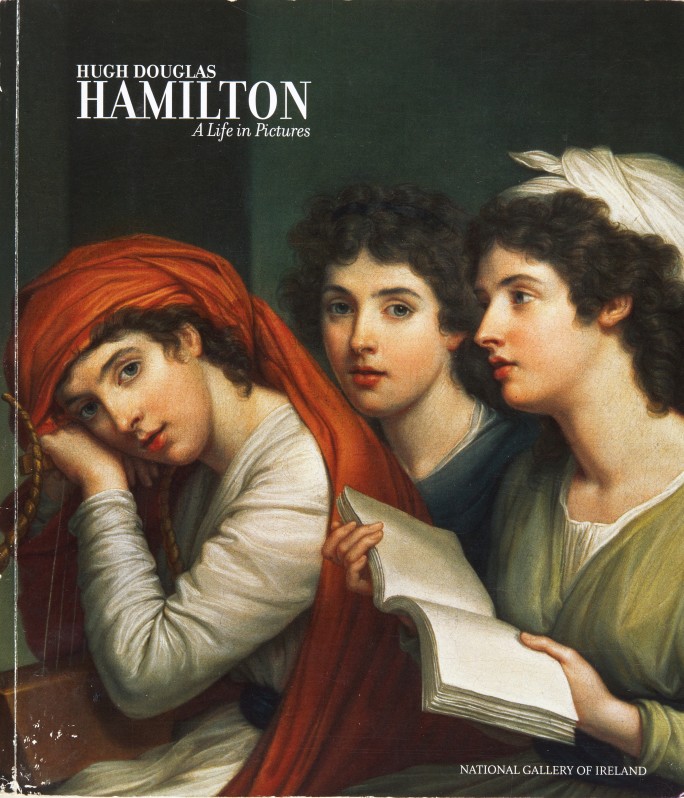

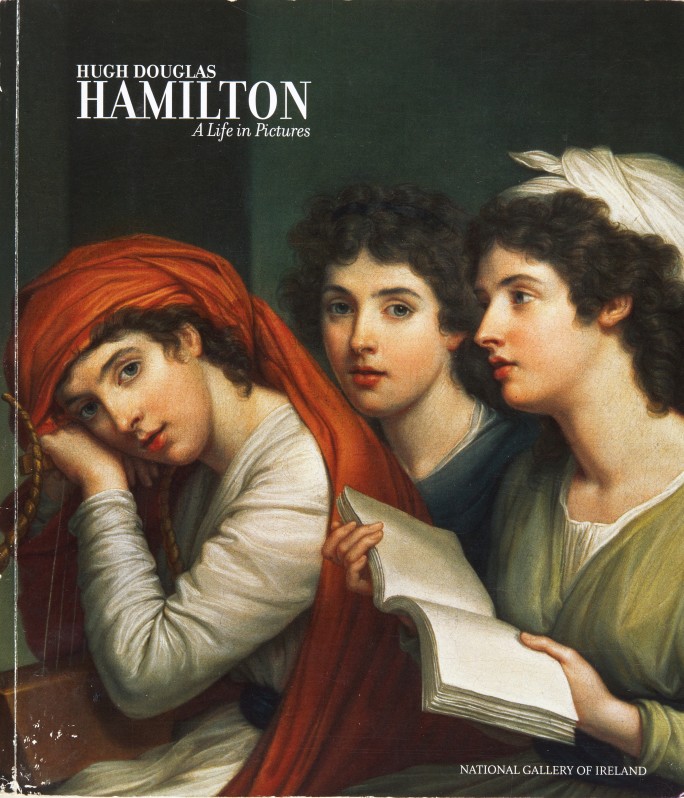

Triple portrait of Emma, Lady Hamilton (1765–1815), as the three Muses

By Hugh Douglas Hamilton (Dublin 1739 - 1808)

Oil on canvas

36.5 x 45 cm.; 14¼ x 17¾ in.

Provenance :

Painted for the sitter’s husband, Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), Palazzo Sessa, Naples ; almost certainly in the collection of William Beckford (1760–1844), Fonthill Abbey and Lansdown Tower, Bath, and thence by descent to his daughter, Susan, who married Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767–1852) ; thence by descent at Hamilton Palace and Lennoxlove House, Scotland.

Catalogue Note

A celebrated model, entertainer and artist’s muse; famous for her ‘Attitudes’ and her creative collaboration with international artists, particularly George Romney; her marriage to the great diplomat, antiquarian and collector Sir William Hamilton, British Envoy to Naples; and her relationship with Admiral Lord Nelson, the ‘Nation’s Hero’; Emma, Lady Hamilton was a cultural icon and European celebrity in the early nineteenth century.

Born Amy Lyon, the daughter of a blacksmith from Cheshire, and later changing her name to Emma Hart, the young girl who was to become Lady Hamilton began her ascent as an actresses’ maid at the Drury Lane Theatre. A talented model and dancer, she first came to prominence at the age of fifteen when she was employed for several months as a hostess and entertainer at Uppark Hall by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh.

In the early 1780s she became the mistress of the Hon. Charles Greville, younger son of the Earl of Warwick and a noted patron of the arts, who introduced her to his friend, the painter George Romney.

Emma was sixteen years old at the time and captivated the artist, quickly becoming his artistic muse – his ‘Divine Emma’ as Romney referred to her. Over and above her physical attraction and youthful beauty, Emma’s early training at Drury Lane had awakened a flair for assuming theatrical poses and expressions. Romney, who had recently returned from Italy where he had re-kindled his desire to create a more elevated genre of portraiture, infused with literary and classical metaphor, found in Emma the perfect model – the physical manifestation of all his conceptions of ideal beauty, with the versatility and emotional range to explore the possibilities of figural representation to a far greater degree that any of his other models.

Romney encouraged and nurtured Emma’s talents, introduced her to the artistic milieu of close friends and patrons that made up his inner circle and exposed her to the cosmopolitan world of a successful London artist.

GEORGE ROMNEY, PORTRAIT OF EMMA HAMILTON A CIRCE, C.1782.

Photo : TATE BRITAIN, LONDON / WIKIMEDIA

Beautiful, witty, possessed of a lively intelligence and keen to discard her humble origins, Emma proved a willing and able pupil. Romney produced over seventy paintings of Emma, over a nine-year period. Remarkable for their breadth, ambition and diversity, they propelled Emma to international fame and stardom. As Christine Riding, Gillian Russell and others explored so comprehensively in the catalogue to the recent 2016–17 exhibition Emma Hamilton. Seduction & Celebrity, they also provided a basis from which she would develop, to such dramatic effect, her famous Attitudes.

On 26 April 1786, her twenty-first birthday, Emma arrived in Naples. She had been sent there by her lover, Greville, to stay with his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, the British Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, on the pretext that Greville would join her there shortly. In reality Greville had found himself a rich heiress to marry and was looking to be rid of Emma. He had secretly persuaded his uncle, who had already met and admired Emma in London, to take her off his hands and by the time Emma realised she had been duped it was too late.

Realising that she was left with few options and that returning to England would leave her in a precarious situation, Emma remained in Italy and became Sir William’s mistress. Despite this inauspicious start, she would eventually marry Hamilton in 1791 and become immortalised to history as Lady Hamilton.

In Naples, in the highly cultured environs of the Palazzo Sessa, Sir William’s official residence, Emma learned to speak French and Italian, took drawing, singing and dancing lessons from the leading teachers, as well as studying history. It was also here, in a house through which an international assortment of royalty, aristocrats, artists, scholars, collectors and connoisseurs flowed, that she learned the skills of a hostess and a diplomat.

Emma was a keen hostess and, whilst Hamilton’s residence had always been a centre of social life, she infused it with a new vitality – Hamilton writing to his nephew Greville that ‘no Princess could do the honours of her Palace with more care & dignity than she does those of my house’.

She became a close confidant of Queen Maria Carolina, the wife of King Ferdinand of Naples and sister of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France and established herself as a leading salonnière, highly praised for her charm and her singing voice.

ELISABETH VIGÉE LE BRUN, PORTRAIT OF EMMA, LADY HAMILTON AS A BACCHANTE, C. 1792.

Image : NATIONAL MUSEUMS LIVERPOOL / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Herself possessing a strong theatrical disposition, and in an effort to maintain a festive and convivial atmosphere at Sir William’s soirees, Emma invited performers and singers to entertain her guests, often joining in the performances herself, singing, dancing and performing her famous Attitudes. A sophisticated form of performance art that, as Gillian Russell has commented, anticipated the work of artists such as Marina Abramović and Sindy Sherman by over two centuries, Emma’s Attitudes were essentially a form of tableaux vivants, inspired by Romney’s idea of combining classical poses with modern allure, mimicking poses from ancient sculpture or Old Master paintings.

In a series of fluid and soundless performances, usually dressed à la grecque in sheer fabric that revealed the contours of her body, she produced a performance that was at once both erotic and learned. This was a unique intervention in the world of connoisseurship and classicism that fitted into a wider contemporary discussion about antiquity, beauty and nature in late eighteenth century Naples. As the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum were bringing the material culture of antiquity out of the ground, Emma’s Attitudes brough that world to life.

Emma’s Attitudes were nothing short of a sensation, attracting visitors from across Europe, and only increased the celebrity that had already been generated through the paintings of George Romney. Using large shawls or veils, draping herself in the folds of cloth, they often evolved into a highly erudite form of charade, with the audience guessing the names of the classical characters and scenes Emma portrayed.

She fêted and was fêted by aristocrats and artists alike and the portraits that the latter produced built up an iconography around her that was simple, pure and natural, often portrayed as an ancient bacchante and setting off a new fashion for a draped Grecian style of dress across Europe. As the more often critical Sir Gilbert Elliot, later 1st Earl of Minto admitted he found Emma ‘all Nature, and yet all Art’.

Her popularity with artists, as well as the pride Hamilton clearly felt for his protégé, is revealed in a letter Emma wrote to her ex-lover Greville in August 1787: ‘there is now five painters and 2 modlers at work on me for Sir William, and there is a picture going of me to the Empress of Russia’.

International artists such as Joshua Reynolds, Gavin Hamilton, Elizabeth Louise Vigée le Brun, Richard Westall and Angelica Kauffman all vied to capture her celebrated charms.

Painted in Italy for Sir William by the Irish artist Hugh Douglas Hamilton, circa 1788–90, here Emma is depicted in the guise of the three classical Muses – Terpsichore (the Muse of choral dance and song), Polymnia (the Muse of sublime hymn), and Calliope (the Muse of eloquence and epic poetry). It is recorded in a manuscript inventory of Sir William’s paintings at the Palazzo Sessa, hanging in the room next to the Library: ‘Lady H. in 3 different views in the same picture – by Hamilton’.

H. D. Hamilton was born and trained in Dublin and was already well known in London as a portraitist, mainly in pastel, before he travelled to Italy in 1779. Whilst in Italy he expanded his practise to increasingly include oils, traditionally considered a more important medium, thus enabling him to increase the scale of his work and develop his repertoire of history painting – in which he was encouraged by the artist John Flaxman.

Primarily based in Rome, he may have visited Naples several times, but he was certainly there in 1788, when he visited Pompeii, and Count di Rezzonico records him being there at a performance of Emma’s Attitudes between 1789 and 1790. Hamilton was well established in the international artistic milieu that existed in Rome at the time.

The gem-engraver Nathaniel Marchant, the sculptor Antonio Canova and the antiquary James Byres were among his closest associates in the city; as was Henry Tresham, his fellow Irish artist come dealer who was based in Rome for fourteen years in Rome and acted as an intermediary between Canova and the celebrated antiquarian and collector John Campbell, 1st Baron Cawdor. Hamilton’s pastel depicting Canova and Tresham deliberating a model of the sculptors famous Cupid and Psyche (Musée du Louvre, Paris), which was originally commissioned by Lord Cawdor, is one of the great masterpieces of the artist’s work in that medium (Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

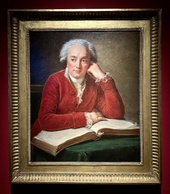

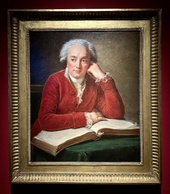

PORTRAIT OF SIR WILLIAM HAMILTON by HUGH DOUGLAS HAMILTON

Image : HAMILTON COLLECTION / PRIVATE COLLECTION

H.D. Hamilton owned the first few volumes of Le Antichità di Ercolano (published between 1757 and 1792), containing drawings of the finds at around the Gulf of Naples at Herculaneum, Pompeii and Stabiae, and he is known to have employed motifs from sculpture studied in Florence and Rome, particularly on the Capitol.

The figure of Emma on the left, with her head and hands resting on a kithara (the ancient Greek seven stringed lyre) is very similar to Hamilton’s pastel portrait of Lady Cowper, painted in Florence (Firle Place, Sussex).

Both Lady Cowper and the Countess of Erne (National Trust, Ickworth) are depicted by Hamilton in similar scarves wrapped around their heads – possibly referencing the fashion that Emma had herself established through her performances.

PIETRO ANTONIO NOVELLI, THE ATTITUDES OF LADY HAMILTON.

Image : NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON / AILSA MELLON BRUCE FUND

Traditionally associated with Dionysus and dramatic poetry, the Muses were said to have been worshiped first by the people of Thespiae at the foot of Mount Helicon. In Homer’s poetry they ‘sing the festive songs at the repasts of the immortals and they bring before the mind of the mortal poet the events which he has to relate and they confer upon him the gift of song’.

Pierre-François Hugues d’Hancarville, in his publication of Sir William Hamilton’s collection of vases, argued that the Muses were responsible for man’s ability to recall his own history and later, as nine muses, they became known more generally as the goddesses credited with inspiration of poetry song. The small and intimate scale, as well as the informality, of this jewel-like cabinet picture clearly shows that it was a work for private contemplation rather than public display, and the depiction of Emma in this way would have been an entirely appropriate complement for Sir William’s own muse.

Emma’s international fame would only increase later when, with the aged Sir William Hamilton in his late sixties. She began a public love affair with Horatio Nelson. Emma first met Nelson when she entertained him upon his arrival in the Bay of Naples to pick up reinforcements in 1793 and captivated the young naval officer with her beauty and charm. Five years later Nelson returned to Naples a living legend and the most famous Englishman in the world, following his victory at the Battle of the Nile.

Emma is said to have flung herself upon him in admiration, calling out 'Oh God, is it possible' as she fainted upon his chest. Nelson's adventures had severely affected his health, however, not least in the loss of his right arm. Emma nursed him under her husband's roof and the two soon after began their passionate affair.

LEMUEL FRANCIS ABBOTT, PORTRAIT OF REAR-ADMIRAL HORATIO NELSON, 1ST VISCOUNT NELSON.

Image : NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH / WIKIMEDIA

In 1799 the Hamilton's were recalled to England and were escorted across Europe by Nelson, travelling via Vienna, before finally being welcomed home by celebratory crowds. The affair, which had been tolerated, perhaps even encouraged, by her husband in Naples, bloomed and in January 1801 Emma gave birth to Nelson's daughter, Horatia. By the autumn of the same year, Nelson bought Merton Place, a small ramshackle house on the outskirts of modern-day Wimbledon. There he lived openly with Emma, Sir William, and Emma's mother, in a ménage à trois that both fascinated and scandalised the public. The newspapers reported on their every move, eventually inducing the Admiralty to send Nelson back to sea, if only to get him away from Emma.

When he died, at the very moment of his greatest achievement aboard H.M.S. Victory at Trafalgar in 1805, Nelson's last request was to have his pigtail sent home to Emma and he left instruction in his will to the British Government that she and Horatia were to be provided for – instructions that were duly ignored.

Note on Provenance

Emma’s husband, Sir William, had died two years earlier in 1803. This painting almost certainly passed, together with a large part of his collection, to his kinsman and close supporter, William Beckford.

Beckford's mother, Maria Hamilton was a cousin of Sir William’s, and the two shared a mutual love of art and antiques. Beckford visited Sir William in Naples in 1780 and again in 1782 and was inspired and aided in his own collecting by his elder relative. In 1791 Sir William and Emma, by then Lady Hamilton, stayed at Fonthill with Beckford during a visit to England and when the Ambassador and his wife retired to England in 1799 they lived for at time at 22 Grosvenor Square, Beckford’s London residence which he lent them.

SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS, PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM BECKFORD, 1782.

Image : NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON. / WIKIMEDIA

In December 1800 Emma gave the last significant performance of her Attitudes at William Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey, where she, Sir William and Nelson were staying as guests for Christmas. Her chief personification on this occasion was that of Agrippina returning to Rome with the ashes of her murdered husband, Germanicus – regarded in the eighteenth century as an exemplary model of the Roman matron and a classical model of fidelity.

The Gentleman’s magazine gave a contemporary eyewitness account of the festivities, describing the grand reception that Lord Nelson and the Hamiltons received upon their arrival:

"As soon as they reached the lodge of the park, the Fonthill volunteers, already waiting, drew up in a double line. Their band of music consisting of thirty performers, playing ‘Rule Britannia’, the corps presented their arms, and marched on either side of the carriages in slow procession up to the house. Here Mr. Beckford, with a large company of gentlemen and ladies, received Lord Nelson and his party on the landing of the grand flight of steps in the portico before the marble hall. The volunteers now formed into a line upon the lawn in front of the house, and fired a feu de joye, whilst the band played ‘God save the King’. The day which had been thick and foggy, cleared up just before Lord Nelson's arrival; so that the military parade and salute, under the command of Capt. Williams, were performed with admirable effect. The company now entered the house, and about six o'clock sat down to dinner. After coffee, a variety of local pieces were finely executed by Lady Hamilton in her expressive and triumphant manner, and by Banti [Brigida Banti, the famous Italian soprano] with all her charms of voice and Italian sensibility."

(...)

Accurate inventories of the notoriously reclusive and private Beckford’s famous collection are scant, and the present work does not appear to be listed in the known records of his collection either at Fonthill or Lansdowne Tower, selective as they are.

Nor does it appear in any of the sale catalogues of items sold from Beckford’s collection to pay off debts towards the end of his life. However, when Beckford died in 1844 a large proportion of his collection, including his celebrated library, were inherited by his favourite daughter Susan, the wife of Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767–1852) and transferred to Hamilton Palace, in Scotland, where this painting is recorded in the collection by the early 1850s.

HAMILTON PALACE, SOUTH LANARKSHIRE, SCOTLAND IN THE 19TH CENTURY.

Image : WIKIMEDIA

However, it is also possible that the painting was transferred directly from Sir William’s collection to Hamilton Palace. Both the future 10th Duke and his father, the future 9th Duke of Hamilton, spent time with Sir William Hamilton in Naples. A distant cousin of Sir William’s the future 10th Duke, who was then simply Mr Alexander Hamilton, stayed at Palazzo Sessa in 1792 and developed an enormous, life-long respect for his relative.

In March that year he wrote to his father, who was then just Lord Archibald Hamilton: ‘[Sir William] is the best man in the world, & I declare next to yourself I do not know where I could find so good a friend’.

Alexander prevailed upon his father to join him in Naples, and the visit was a great success. The future 10th Duke regarded Sir William as a model, both as a man and a collector, and he went on to acquire some of the key works from his collection – notably Rubens's The Loves of the Centaurs (now in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon) in 1810 and the ‘Leonardo’ Laughing Boy (now attributed to Bernardino Luini, at Elton Hall) in 1822.

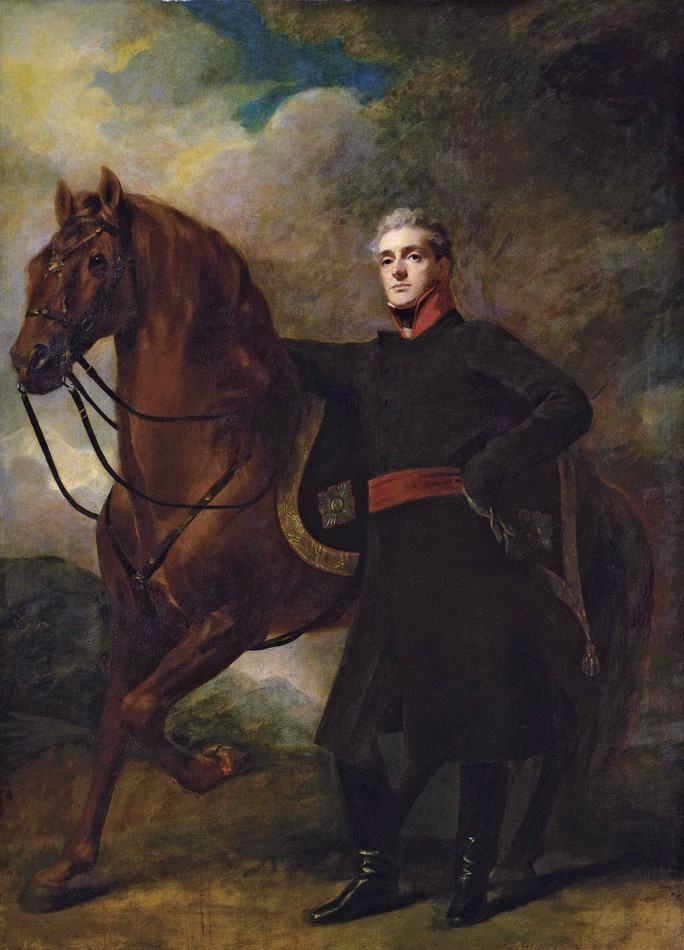

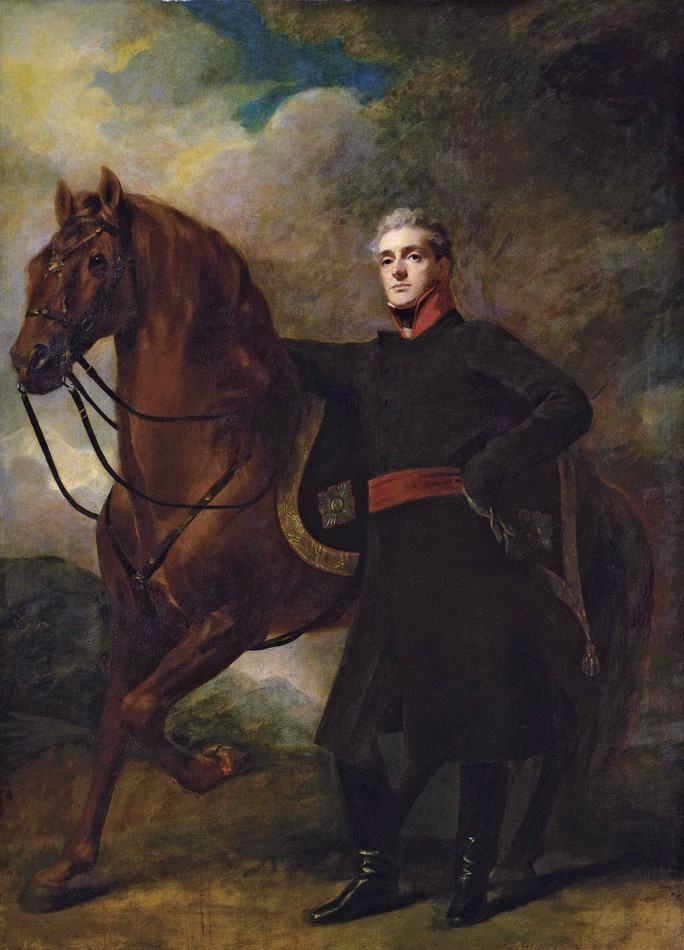

SIR HENRY RAEBURN, PORTRAIT OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON, 10TH DUKE OF HAMILTON AND 7TH DUKE OF BRANDON.

Image : HAMILTON COLLECTION / WIKIMEDIA

Two further surviving versions exist of this triple portrait of Emma, Lady Hamilton, both similar in size. An oil, formerly in the collection of John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick, a close associate of Sir William Hamilton’s (Private collection, England); and a pastel, formerly in the collection of the Earl of Ilchester, a descendent of Lady Holland, who spent a long period in Naples in the early 1790s (present whereabouts unknown).

John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick visited Italy in 1790 and became friends with Sir William Hamilton, Emma and Lord Nelson, as well as many other eminent connoisseurs and men of learning Edward Gibbon, Richard Payne Knight, and the Italian artists Antonio Canova and Vincenzo Camuccini. In 1798 he was living at the Bay of Palermo when HMS Vanguard, under the command of Captain Edward Berry, became stranded there and, as a result, was the first man in Europe to receive news of the victory of the Battle of the Nile – receiving the news from Nelson himself.

The painting has remained in the great Hamilton Palace Collection ever since. Following the sale and eventual demolition of the Palace itself in 1921, in the 13th Duke’s time, the picture hung at the family’s London residence, Cleveland House in St James’s Square, where it laboured under a misattribution to Angelica Kauffman and the identification of the sitter as Lady Hamilton was lost.

During the course of the twentieth century alternative attributions to Gavin Hamilton and the Austrian painter Ludwig Guttenbrunn were both suggested, until its true attribution and identity were finally rediscovered in the mid-1990s, when the picture was exhibited in the seminal Vases & Volcanoes exhibition at the British Museum, dedicated to Sir William Hamilton’s great collection and activities as an antiquarian. In the catalogue Kim Sloan correctly identified it as being by Hugh Douglas Hamilton and associated it with the entry in the inventory of Sir William Hamilton’s collection of paintings at the Palazzo Sessa in the British Library.

It was later exhibited in the major retrospective of Hamilton’s work held at the National Gallery of Ireland, in Dublin, in 2008–09, for which this painting was used as the cover illustration to the catalogue.

FRONT COVER OF THE CATALOGUE FOR THE 2008 EXHIBITION HUGH DOUGLAS HAMILTON (1740–1808) : A LIFE IN PICTURES AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND, DUBLIN, ILLUSTRATING THE PRESENT LOT

* Source et infos complémentaires : Sotheby's London - Old Masters Evening Sale (7 July 2021)

Je cite des extraits de l'interminable note au catalogue

Triple portrait of Emma, Lady Hamilton (1765–1815), as the three Muses

By Hugh Douglas Hamilton (Dublin 1739 - 1808)

Oil on canvas

36.5 x 45 cm.; 14¼ x 17¾ in.

Provenance :

Painted for the sitter’s husband, Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), Palazzo Sessa, Naples ; almost certainly in the collection of William Beckford (1760–1844), Fonthill Abbey and Lansdown Tower, Bath, and thence by descent to his daughter, Susan, who married Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767–1852) ; thence by descent at Hamilton Palace and Lennoxlove House, Scotland.

Catalogue Note

A celebrated model, entertainer and artist’s muse; famous for her ‘Attitudes’ and her creative collaboration with international artists, particularly George Romney; her marriage to the great diplomat, antiquarian and collector Sir William Hamilton, British Envoy to Naples; and her relationship with Admiral Lord Nelson, the ‘Nation’s Hero’; Emma, Lady Hamilton was a cultural icon and European celebrity in the early nineteenth century.

Born Amy Lyon, the daughter of a blacksmith from Cheshire, and later changing her name to Emma Hart, the young girl who was to become Lady Hamilton began her ascent as an actresses’ maid at the Drury Lane Theatre. A talented model and dancer, she first came to prominence at the age of fifteen when she was employed for several months as a hostess and entertainer at Uppark Hall by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh.

In the early 1780s she became the mistress of the Hon. Charles Greville, younger son of the Earl of Warwick and a noted patron of the arts, who introduced her to his friend, the painter George Romney.

Emma was sixteen years old at the time and captivated the artist, quickly becoming his artistic muse – his ‘Divine Emma’ as Romney referred to her. Over and above her physical attraction and youthful beauty, Emma’s early training at Drury Lane had awakened a flair for assuming theatrical poses and expressions. Romney, who had recently returned from Italy where he had re-kindled his desire to create a more elevated genre of portraiture, infused with literary and classical metaphor, found in Emma the perfect model – the physical manifestation of all his conceptions of ideal beauty, with the versatility and emotional range to explore the possibilities of figural representation to a far greater degree that any of his other models.

Romney encouraged and nurtured Emma’s talents, introduced her to the artistic milieu of close friends and patrons that made up his inner circle and exposed her to the cosmopolitan world of a successful London artist.

GEORGE ROMNEY, PORTRAIT OF EMMA HAMILTON A CIRCE, C.1782.

Photo : TATE BRITAIN, LONDON / WIKIMEDIA

Beautiful, witty, possessed of a lively intelligence and keen to discard her humble origins, Emma proved a willing and able pupil. Romney produced over seventy paintings of Emma, over a nine-year period. Remarkable for their breadth, ambition and diversity, they propelled Emma to international fame and stardom. As Christine Riding, Gillian Russell and others explored so comprehensively in the catalogue to the recent 2016–17 exhibition Emma Hamilton. Seduction & Celebrity, they also provided a basis from which she would develop, to such dramatic effect, her famous Attitudes.

On 26 April 1786, her twenty-first birthday, Emma arrived in Naples. She had been sent there by her lover, Greville, to stay with his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, the British Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, on the pretext that Greville would join her there shortly. In reality Greville had found himself a rich heiress to marry and was looking to be rid of Emma. He had secretly persuaded his uncle, who had already met and admired Emma in London, to take her off his hands and by the time Emma realised she had been duped it was too late.

Realising that she was left with few options and that returning to England would leave her in a precarious situation, Emma remained in Italy and became Sir William’s mistress. Despite this inauspicious start, she would eventually marry Hamilton in 1791 and become immortalised to history as Lady Hamilton.

In Naples, in the highly cultured environs of the Palazzo Sessa, Sir William’s official residence, Emma learned to speak French and Italian, took drawing, singing and dancing lessons from the leading teachers, as well as studying history. It was also here, in a house through which an international assortment of royalty, aristocrats, artists, scholars, collectors and connoisseurs flowed, that she learned the skills of a hostess and a diplomat.

Emma was a keen hostess and, whilst Hamilton’s residence had always been a centre of social life, she infused it with a new vitality – Hamilton writing to his nephew Greville that ‘no Princess could do the honours of her Palace with more care & dignity than she does those of my house’.

She became a close confidant of Queen Maria Carolina, the wife of King Ferdinand of Naples and sister of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France and established herself as a leading salonnière, highly praised for her charm and her singing voice.

ELISABETH VIGÉE LE BRUN, PORTRAIT OF EMMA, LADY HAMILTON AS A BACCHANTE, C. 1792.

Image : NATIONAL MUSEUMS LIVERPOOL / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Herself possessing a strong theatrical disposition, and in an effort to maintain a festive and convivial atmosphere at Sir William’s soirees, Emma invited performers and singers to entertain her guests, often joining in the performances herself, singing, dancing and performing her famous Attitudes. A sophisticated form of performance art that, as Gillian Russell has commented, anticipated the work of artists such as Marina Abramović and Sindy Sherman by over two centuries, Emma’s Attitudes were essentially a form of tableaux vivants, inspired by Romney’s idea of combining classical poses with modern allure, mimicking poses from ancient sculpture or Old Master paintings.

In a series of fluid and soundless performances, usually dressed à la grecque in sheer fabric that revealed the contours of her body, she produced a performance that was at once both erotic and learned. This was a unique intervention in the world of connoisseurship and classicism that fitted into a wider contemporary discussion about antiquity, beauty and nature in late eighteenth century Naples. As the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum were bringing the material culture of antiquity out of the ground, Emma’s Attitudes brough that world to life.

Emma’s Attitudes were nothing short of a sensation, attracting visitors from across Europe, and only increased the celebrity that had already been generated through the paintings of George Romney. Using large shawls or veils, draping herself in the folds of cloth, they often evolved into a highly erudite form of charade, with the audience guessing the names of the classical characters and scenes Emma portrayed.

She fêted and was fêted by aristocrats and artists alike and the portraits that the latter produced built up an iconography around her that was simple, pure and natural, often portrayed as an ancient bacchante and setting off a new fashion for a draped Grecian style of dress across Europe. As the more often critical Sir Gilbert Elliot, later 1st Earl of Minto admitted he found Emma ‘all Nature, and yet all Art’.

Her popularity with artists, as well as the pride Hamilton clearly felt for his protégé, is revealed in a letter Emma wrote to her ex-lover Greville in August 1787: ‘there is now five painters and 2 modlers at work on me for Sir William, and there is a picture going of me to the Empress of Russia’.

International artists such as Joshua Reynolds, Gavin Hamilton, Elizabeth Louise Vigée le Brun, Richard Westall and Angelica Kauffman all vied to capture her celebrated charms.

Painted in Italy for Sir William by the Irish artist Hugh Douglas Hamilton, circa 1788–90, here Emma is depicted in the guise of the three classical Muses – Terpsichore (the Muse of choral dance and song), Polymnia (the Muse of sublime hymn), and Calliope (the Muse of eloquence and epic poetry). It is recorded in a manuscript inventory of Sir William’s paintings at the Palazzo Sessa, hanging in the room next to the Library: ‘Lady H. in 3 different views in the same picture – by Hamilton’.

H. D. Hamilton was born and trained in Dublin and was already well known in London as a portraitist, mainly in pastel, before he travelled to Italy in 1779. Whilst in Italy he expanded his practise to increasingly include oils, traditionally considered a more important medium, thus enabling him to increase the scale of his work and develop his repertoire of history painting – in which he was encouraged by the artist John Flaxman.

Primarily based in Rome, he may have visited Naples several times, but he was certainly there in 1788, when he visited Pompeii, and Count di Rezzonico records him being there at a performance of Emma’s Attitudes between 1789 and 1790. Hamilton was well established in the international artistic milieu that existed in Rome at the time.

The gem-engraver Nathaniel Marchant, the sculptor Antonio Canova and the antiquary James Byres were among his closest associates in the city; as was Henry Tresham, his fellow Irish artist come dealer who was based in Rome for fourteen years in Rome and acted as an intermediary between Canova and the celebrated antiquarian and collector John Campbell, 1st Baron Cawdor. Hamilton’s pastel depicting Canova and Tresham deliberating a model of the sculptors famous Cupid and Psyche (Musée du Louvre, Paris), which was originally commissioned by Lord Cawdor, is one of the great masterpieces of the artist’s work in that medium (Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

PORTRAIT OF SIR WILLIAM HAMILTON by HUGH DOUGLAS HAMILTON

Image : HAMILTON COLLECTION / PRIVATE COLLECTION

H.D. Hamilton owned the first few volumes of Le Antichità di Ercolano (published between 1757 and 1792), containing drawings of the finds at around the Gulf of Naples at Herculaneum, Pompeii and Stabiae, and he is known to have employed motifs from sculpture studied in Florence and Rome, particularly on the Capitol.

The figure of Emma on the left, with her head and hands resting on a kithara (the ancient Greek seven stringed lyre) is very similar to Hamilton’s pastel portrait of Lady Cowper, painted in Florence (Firle Place, Sussex).

Both Lady Cowper and the Countess of Erne (National Trust, Ickworth) are depicted by Hamilton in similar scarves wrapped around their heads – possibly referencing the fashion that Emma had herself established through her performances.

PIETRO ANTONIO NOVELLI, THE ATTITUDES OF LADY HAMILTON.

Image : NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON / AILSA MELLON BRUCE FUND

Traditionally associated with Dionysus and dramatic poetry, the Muses were said to have been worshiped first by the people of Thespiae at the foot of Mount Helicon. In Homer’s poetry they ‘sing the festive songs at the repasts of the immortals and they bring before the mind of the mortal poet the events which he has to relate and they confer upon him the gift of song’.

Pierre-François Hugues d’Hancarville, in his publication of Sir William Hamilton’s collection of vases, argued that the Muses were responsible for man’s ability to recall his own history and later, as nine muses, they became known more generally as the goddesses credited with inspiration of poetry song. The small and intimate scale, as well as the informality, of this jewel-like cabinet picture clearly shows that it was a work for private contemplation rather than public display, and the depiction of Emma in this way would have been an entirely appropriate complement for Sir William’s own muse.

Emma’s international fame would only increase later when, with the aged Sir William Hamilton in his late sixties. She began a public love affair with Horatio Nelson. Emma first met Nelson when she entertained him upon his arrival in the Bay of Naples to pick up reinforcements in 1793 and captivated the young naval officer with her beauty and charm. Five years later Nelson returned to Naples a living legend and the most famous Englishman in the world, following his victory at the Battle of the Nile.

Emma is said to have flung herself upon him in admiration, calling out 'Oh God, is it possible' as she fainted upon his chest. Nelson's adventures had severely affected his health, however, not least in the loss of his right arm. Emma nursed him under her husband's roof and the two soon after began their passionate affair.

LEMUEL FRANCIS ABBOTT, PORTRAIT OF REAR-ADMIRAL HORATIO NELSON, 1ST VISCOUNT NELSON.

Image : NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH / WIKIMEDIA

In 1799 the Hamilton's were recalled to England and were escorted across Europe by Nelson, travelling via Vienna, before finally being welcomed home by celebratory crowds. The affair, which had been tolerated, perhaps even encouraged, by her husband in Naples, bloomed and in January 1801 Emma gave birth to Nelson's daughter, Horatia. By the autumn of the same year, Nelson bought Merton Place, a small ramshackle house on the outskirts of modern-day Wimbledon. There he lived openly with Emma, Sir William, and Emma's mother, in a ménage à trois that both fascinated and scandalised the public. The newspapers reported on their every move, eventually inducing the Admiralty to send Nelson back to sea, if only to get him away from Emma.

When he died, at the very moment of his greatest achievement aboard H.M.S. Victory at Trafalgar in 1805, Nelson's last request was to have his pigtail sent home to Emma and he left instruction in his will to the British Government that she and Horatia were to be provided for – instructions that were duly ignored.

Note on Provenance

Emma’s husband, Sir William, had died two years earlier in 1803. This painting almost certainly passed, together with a large part of his collection, to his kinsman and close supporter, William Beckford.

Beckford's mother, Maria Hamilton was a cousin of Sir William’s, and the two shared a mutual love of art and antiques. Beckford visited Sir William in Naples in 1780 and again in 1782 and was inspired and aided in his own collecting by his elder relative. In 1791 Sir William and Emma, by then Lady Hamilton, stayed at Fonthill with Beckford during a visit to England and when the Ambassador and his wife retired to England in 1799 they lived for at time at 22 Grosvenor Square, Beckford’s London residence which he lent them.

SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS, PORTRAIT OF WILLIAM BECKFORD, 1782.

Image : NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON. / WIKIMEDIA

In December 1800 Emma gave the last significant performance of her Attitudes at William Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey, where she, Sir William and Nelson were staying as guests for Christmas. Her chief personification on this occasion was that of Agrippina returning to Rome with the ashes of her murdered husband, Germanicus – regarded in the eighteenth century as an exemplary model of the Roman matron and a classical model of fidelity.

The Gentleman’s magazine gave a contemporary eyewitness account of the festivities, describing the grand reception that Lord Nelson and the Hamiltons received upon their arrival:

"As soon as they reached the lodge of the park, the Fonthill volunteers, already waiting, drew up in a double line. Their band of music consisting of thirty performers, playing ‘Rule Britannia’, the corps presented their arms, and marched on either side of the carriages in slow procession up to the house. Here Mr. Beckford, with a large company of gentlemen and ladies, received Lord Nelson and his party on the landing of the grand flight of steps in the portico before the marble hall. The volunteers now formed into a line upon the lawn in front of the house, and fired a feu de joye, whilst the band played ‘God save the King’. The day which had been thick and foggy, cleared up just before Lord Nelson's arrival; so that the military parade and salute, under the command of Capt. Williams, were performed with admirable effect. The company now entered the house, and about six o'clock sat down to dinner. After coffee, a variety of local pieces were finely executed by Lady Hamilton in her expressive and triumphant manner, and by Banti [Brigida Banti, the famous Italian soprano] with all her charms of voice and Italian sensibility."

(...)

Accurate inventories of the notoriously reclusive and private Beckford’s famous collection are scant, and the present work does not appear to be listed in the known records of his collection either at Fonthill or Lansdowne Tower, selective as they are.

Nor does it appear in any of the sale catalogues of items sold from Beckford’s collection to pay off debts towards the end of his life. However, when Beckford died in 1844 a large proportion of his collection, including his celebrated library, were inherited by his favourite daughter Susan, the wife of Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767–1852) and transferred to Hamilton Palace, in Scotland, where this painting is recorded in the collection by the early 1850s.

HAMILTON PALACE, SOUTH LANARKSHIRE, SCOTLAND IN THE 19TH CENTURY.

Image : WIKIMEDIA

However, it is also possible that the painting was transferred directly from Sir William’s collection to Hamilton Palace. Both the future 10th Duke and his father, the future 9th Duke of Hamilton, spent time with Sir William Hamilton in Naples. A distant cousin of Sir William’s the future 10th Duke, who was then simply Mr Alexander Hamilton, stayed at Palazzo Sessa in 1792 and developed an enormous, life-long respect for his relative.

In March that year he wrote to his father, who was then just Lord Archibald Hamilton: ‘[Sir William] is the best man in the world, & I declare next to yourself I do not know where I could find so good a friend’.

Alexander prevailed upon his father to join him in Naples, and the visit was a great success. The future 10th Duke regarded Sir William as a model, both as a man and a collector, and he went on to acquire some of the key works from his collection – notably Rubens's The Loves of the Centaurs (now in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon) in 1810 and the ‘Leonardo’ Laughing Boy (now attributed to Bernardino Luini, at Elton Hall) in 1822.

SIR HENRY RAEBURN, PORTRAIT OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON, 10TH DUKE OF HAMILTON AND 7TH DUKE OF BRANDON.

Image : HAMILTON COLLECTION / WIKIMEDIA

Two further surviving versions exist of this triple portrait of Emma, Lady Hamilton, both similar in size. An oil, formerly in the collection of John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick, a close associate of Sir William Hamilton’s (Private collection, England); and a pastel, formerly in the collection of the Earl of Ilchester, a descendent of Lady Holland, who spent a long period in Naples in the early 1790s (present whereabouts unknown).

John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick visited Italy in 1790 and became friends with Sir William Hamilton, Emma and Lord Nelson, as well as many other eminent connoisseurs and men of learning Edward Gibbon, Richard Payne Knight, and the Italian artists Antonio Canova and Vincenzo Camuccini. In 1798 he was living at the Bay of Palermo when HMS Vanguard, under the command of Captain Edward Berry, became stranded there and, as a result, was the first man in Europe to receive news of the victory of the Battle of the Nile – receiving the news from Nelson himself.

The painting has remained in the great Hamilton Palace Collection ever since. Following the sale and eventual demolition of the Palace itself in 1921, in the 13th Duke’s time, the picture hung at the family’s London residence, Cleveland House in St James’s Square, where it laboured under a misattribution to Angelica Kauffman and the identification of the sitter as Lady Hamilton was lost.

During the course of the twentieth century alternative attributions to Gavin Hamilton and the Austrian painter Ludwig Guttenbrunn were both suggested, until its true attribution and identity were finally rediscovered in the mid-1990s, when the picture was exhibited in the seminal Vases & Volcanoes exhibition at the British Museum, dedicated to Sir William Hamilton’s great collection and activities as an antiquarian. In the catalogue Kim Sloan correctly identified it as being by Hugh Douglas Hamilton and associated it with the entry in the inventory of Sir William Hamilton’s collection of paintings at the Palazzo Sessa in the British Library.

It was later exhibited in the major retrospective of Hamilton’s work held at the National Gallery of Ireland, in Dublin, in 2008–09, for which this painting was used as the cover illustration to the catalogue.

FRONT COVER OF THE CATALOGUE FOR THE 2008 EXHIBITION HUGH DOUGLAS HAMILTON (1740–1808) : A LIFE IN PICTURES AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND, DUBLIN, ILLUSTRATING THE PRESENT LOT

* Source et infos complémentaires : Sotheby's London - Old Masters Evening Sale (7 July 2021)

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Ce portrait est de toute beauté ; la retranscription du visage dans ces différentes attitudes est superbe. C'est très intimiste.

capin- Messages : 67

Date d'inscription : 28/01/2018

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Re: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

Oui. D'autant plus " intime " que le tableau est d'un petit format...

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18138

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Page 5 sur 6 •  1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» Le vice-amiral Horatio Nelson, 1er vicomte Nelson, dit Lord Nelson

» Lady Elizabeth Berkeley, dite Lady Craven (1750-1828)

» Lady Anne Barnard

» Lady Elisabeth Foster

» Ventes aux enchères 2019

» Lady Elizabeth Berkeley, dite Lady Craven (1750-1828)

» Lady Anne Barnard

» Lady Elisabeth Foster

» Ventes aux enchères 2019

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La famille royale et les contemporains de Marie-Antoinette :: Autres contemporains : les femmes du XVIIIe siècle

Page 5 sur 6

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum