Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

+15

Vicq d Azir

Calonne

Trianon

Gouverneur Morris

fleurdelys

Bohème96

Lucius

mignardise

MARIE ANTOINETTE

La nuit, la neige

Olivier

Mme de Sabran

Comte d'Hézècques

Comtesse Diane

Mr de Talaru

19 participants

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La famille royale et les contemporains de Marie-Antoinette :: Autres contemporains : les femmes du XVIIIe siècle

Page 6 sur 6

Page 6 sur 6 •  1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55509

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Voici une série radiophonique diffusée semaine dernière sur Europe 1, émission Au coeur de l'Histoire :

Présentation :

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est considérée comme la plus grande portraitiste du XVIIIe siècle. Son talent a fait d’elle la coqueluche de Paris et une intime de la reine Marie-Antoinette qu’elle a peinte à de nombreuses reprises, à Versailles. Mais la Révolution va la mettre en danger et l’obliger à quitter la France.

Dans cet épisode du podcast "Au cœur de l’Histoire" produit par Europe 1 Studio, Virginie Girod remonte au début de l’histoire d’Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, une peintre qui dès son enfance a côtoyé de très nombreux artistes.

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat (Detail)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1782

Signed copy by the artist of a very popular self portrait that she painted in 1782, now in collection of the baronne Edmond de Rothschild

Image : The National Gallery

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 1)

Alors qu’elle n’est encore qu’une enfant, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun dessine : elle a 6 ans, elle vit dans un couvent et elle s’exerce avec un simple morceau de charbon. La peintre, qui sera bientôt considérée comme la plus grande portraitiste du XVIIIe siècle, fréquente très tôt des artistes, rencontrés par le biais de son père, lui-même pastelliste. Mais il meurt alors qu’elle n’a que 12 ans. Comment la jeune Elisabeth va-t-elle alors faire du dessin un métier à part entière pour nourrir sa famille ? Qui sont ses premiers clients ? Et comment fait-elle finalement la rencontre de Marie-Antoinette ?

Virginie Girod retrace le parcours de Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, arrivée à Versailles à l'âge de 25 ans seulement pour sa première séance de pose officielle face à la Reine.

A écouter ici (durée 15 mn) : Europe 1 - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 1)

A écouter ici (durée 15 mn) : Europe 1 - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 1)

Self-portrait

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

oil on canvas, c. 1781

Image : Kimbell Art Museum / Commons Wikimedia

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 2)

Alors que la Révolution commence à gronder en 1789, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, portraitiste de la Reine, qui a provoqué scandale et admiration avec plusieurs de ses tableaux, sent le danger venir. Bouleversée par les premières violences, prise de panique, l'artiste commence à préparer son départ pour l’étranger. Mais une foule de gardes nationaux fait irruption chez elle… Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun va-t-elle réussir à quitter Paris ? Quelle vie peut-elle se réinventer ailleurs, sans perdre son goût pour l’art et son talent de portraitiste ? Virginie Girod retrace le parcours de Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, une artiste exceptionnelle, reconnue en France et à l’étranger, et témoin à sa façon d’un monde qui bascule.

A écouter ici (durée 17 mn) : Europe 1 - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 2)

A écouter ici (durée 17 mn) : Europe 1 - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 2)

Autoportrait de l’artiste peignant le portrait de l’impératrice Maria Féodorovna

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Huile sur toile, c. 1800

Image : Musée de l'Ermitage, Saint-Pétersbourg

Toujours sur Europe 1 et en complément : l'interview de Cécile Berly

Toujours sur Europe 1 et en complément : l'interview de Cécile Berly

La peintre Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun "est une femme des Lumières

Virginie Girod reçoit Cécile Berly, historienne spécialiste du XVIIIe siècle, auteure notamment de "La légèreté et le grave : une histoire du XVIIIe siècle en tableaux" (Editions Passés Composés), pour s’intéresser à Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, "l'un des plus grands génies de la peinture" de son époque. Installée à Versailles, proche de la Reine, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun a réalisé de très nombreux autoportraits avec sa fille Julie, évoquant la maternité, "un sujet assez novateur parce qu'il n'est pas religieux, parce qu'il n'est pas biblique". Pourquoi ses peintures de Marie-Antoinette ont-elles également créé "une révolution avant la Révolution" ? Et en quoi l’artiste agit-elle "en femme des Lumières même si elle est royaliste et ultra-conservatrice" ?

A écouter ici (durée 14 mn) : Europe 1 - La peintre Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun est une femme des Lumières

A écouter ici (durée 14 mn) : Europe 1 - La peintre Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun est une femme des Lumières

La Paix ramenant l'Abondance

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Huile sur toile, 1780

Image : Musée du Louvre

Présentation :

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est considérée comme la plus grande portraitiste du XVIIIe siècle. Son talent a fait d’elle la coqueluche de Paris et une intime de la reine Marie-Antoinette qu’elle a peinte à de nombreuses reprises, à Versailles. Mais la Révolution va la mettre en danger et l’obliger à quitter la France.

Dans cet épisode du podcast "Au cœur de l’Histoire" produit par Europe 1 Studio, Virginie Girod remonte au début de l’histoire d’Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, une peintre qui dès son enfance a côtoyé de très nombreux artistes.

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat (Detail)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1782

Signed copy by the artist of a very popular self portrait that she painted in 1782, now in collection of the baronne Edmond de Rothschild

Image : The National Gallery

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 1)

Alors qu’elle n’est encore qu’une enfant, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun dessine : elle a 6 ans, elle vit dans un couvent et elle s’exerce avec un simple morceau de charbon. La peintre, qui sera bientôt considérée comme la plus grande portraitiste du XVIIIe siècle, fréquente très tôt des artistes, rencontrés par le biais de son père, lui-même pastelliste. Mais il meurt alors qu’elle n’a que 12 ans. Comment la jeune Elisabeth va-t-elle alors faire du dessin un métier à part entière pour nourrir sa famille ? Qui sont ses premiers clients ? Et comment fait-elle finalement la rencontre de Marie-Antoinette ?

Virginie Girod retrace le parcours de Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, arrivée à Versailles à l'âge de 25 ans seulement pour sa première séance de pose officielle face à la Reine.

Self-portrait

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

oil on canvas, c. 1781

Image : Kimbell Art Museum / Commons Wikimedia

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, les couleurs de l'émancipation (partie 2)

Alors que la Révolution commence à gronder en 1789, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, portraitiste de la Reine, qui a provoqué scandale et admiration avec plusieurs de ses tableaux, sent le danger venir. Bouleversée par les premières violences, prise de panique, l'artiste commence à préparer son départ pour l’étranger. Mais une foule de gardes nationaux fait irruption chez elle… Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun va-t-elle réussir à quitter Paris ? Quelle vie peut-elle se réinventer ailleurs, sans perdre son goût pour l’art et son talent de portraitiste ? Virginie Girod retrace le parcours de Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, une artiste exceptionnelle, reconnue en France et à l’étranger, et témoin à sa façon d’un monde qui bascule.

Autoportrait de l’artiste peignant le portrait de l’impératrice Maria Féodorovna

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Huile sur toile, c. 1800

Image : Musée de l'Ermitage, Saint-Pétersbourg

La peintre Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun "est une femme des Lumières

Virginie Girod reçoit Cécile Berly, historienne spécialiste du XVIIIe siècle, auteure notamment de "La légèreté et le grave : une histoire du XVIIIe siècle en tableaux" (Editions Passés Composés), pour s’intéresser à Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, "l'un des plus grands génies de la peinture" de son époque. Installée à Versailles, proche de la Reine, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun a réalisé de très nombreux autoportraits avec sa fille Julie, évoquant la maternité, "un sujet assez novateur parce qu'il n'est pas religieux, parce qu'il n'est pas biblique". Pourquoi ses peintures de Marie-Antoinette ont-elles également créé "une révolution avant la Révolution" ? Et en quoi l’artiste agit-elle "en femme des Lumières même si elle est royaliste et ultra-conservatrice" ?

La Paix ramenant l'Abondance

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Huile sur toile, 1780

Image : Musée du Louvre

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

, mais bon...je vous présente tout de même ce buste, prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères et décrit comme :

, mais bon...je vous présente tout de même ce buste, prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères et décrit comme : Grand buste en terre cuite, Madame Vigée-Lebrun

Augustin Pajou (1730-1809)

Bronze, patine brun foncé.

Hauteur du buste 58 cm.

Hauteur totale avec le socle rond en marbre 72 cm.

Au dos, signature "Pajou f. 1783" gravée dans l'argile encore humide et cuite en même temps

Note au catalogue :

Texte original, en allemand

- Spoiler:

- Pajou zählte zu den bedeutendsten französischen Bildhauern seiner Zeit und demgemäß auch zu den häufig vom Hof beauftragten Porträtisten für Büsten. Bereits 14-jährig wurde er Schüler des Jean-Baptist Lemoyne, mit 18 Jahren errang er den 1. Preis des Prix de Rome an der Academie Royal, was ihm Studienaufenthalte in Italien ermöglichte. Sein Können verschaffte ihm schnell Ansehen bei Hofe und das Wohlwollen des französischen Königs Louis XV sowie der Madame du Barry, deren Büsten sich heute im Louvre sowie im Museum of Fine Arts in Boston befinden. Neben weiteren Büsten von Persönlichkeiten höchsten Ranges am Hof entstanden etwa auch die von Marie-Antoinette und des Dauphin von 1781 (Museum Brüssel).

Neben diesen Porträtaufträgen wurde Pajou auch an der Ausgestaltung öffentlicher Gebäude beauftragt, wie der Oper in Versailles, dem Palais Royal oder dem Palais de Justice. Während der Revolutionsjahre zog er sich nach Montpellier zurück, wurde jedoch von Napoleon erneut beauftragt.

Die Büste ist in Lebensgröße gearbeitet, gebrannt in rötlichem Ton. Die Anschnitte der Schultern vom Kleid bedeckt, das anmutige Gesicht nach links gerichtet, mit intelligentem, aber uneitlem Ausdruck. Das Haar fällt in Locken zur Schulter herab.

Eine Identifizierung lag hier bislang nicht vor. Der Vergleich mit einer weiteren, in den Kunsthandel gelangten Büste (H. 63 cm), als „Madame Vigée-Lebrun“ bezeichnet, liegt jedoch aufgrund der überzeugenden Ähnlichkeit nahe, dass es sich auch hier um das Bildnis dieser berühmten Künstlerin handelt.

Louise-Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755 Paris - 1842) zählt ebenso zu den bedeutenden Künstlerpersönlichkeiten ihrer Zeit. Als Malerin und Schülerin von Claude Joseph Vernet, hatte auch sie enge Beziehungen zum Hof, war sie doch auch Gattin eines Nachkommen von Charles Lebrun, der die bedeutende Rolle als Maler in Paris und Versailles am Hof Ludwigs XIV. einnahm. Sie wurde trotz Intrigen aufgrund der Förderung des Königs in die Königliche Akademie der Malerei und Bildhauerei aufgenommen und schuf danach zahlreiche Porträts der Hofgesellschaft.

Damit war sie, wenngleich zwanzig Jahre jünger als Pajou, gewissermaßen Künstlerkollegin. Dies erklärt, dass sie wohl aus dieser Begegnung von Pajou in Lebensgröße porträtiert wurde. Die Ähnlichkeit mit der oben genannten kleineren Tonbüste bezieht sich auf einige Übereinstimmungen, wie die Haarlocken, vor allem das Gesicht; jedoch ist die Draperie des Kleides völlig anders gestaltet; anstelle des dortigen schrägen Bandes, das über dem Oberkörper in Art einer jugendlich-antiken Mode eng anliegt, ist hier der Spitzensaum der Bluse gezeigt, was darauf schließen lässt, dass die vier vorliegende Büste etwas später entstand. Gemäß der Datierung ist die Malerin hier im Alter von 28 Jahren gezeigt. A.R. (1370629) (11)

Traduction approximative Google

Pajou comptait parmi les plus grands sculpteurs français de son temps et, par conséquent, parmi les portraitistes souvent commandés par la cour pour des bustes. Dès l'âge de 14 ans, il devint l'élève de Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, et à 18 ans, il remporta le premier prix de Rome à l'Académie royale, ce qui lui permit de faire des séjours d'études en Italie. Son talent lui valut rapidement la considération de la cour et la bienveillance du roi de France Louis XV ainsi que de Madame du Barry, dont les bustes se trouvent aujourd'hui au Louvre ainsi qu'au Museum of Fine Arts de Boston. Outre d'autres bustes de personnalités de haut rang à la cour, il réalisa également ceux de Marie-Antoinette et du Dauphin en 1781 (musée de Bruxelles).

Outre ces commandes de portraits, Pajou fut également chargé de la décoration de bâtiments publics, comme l'Opéra de Versailles, le Palais Royal ou le Palais de Justice. Pendant les années révolutionnaires, il se retire à Montpellier, mais Napoléon lui passe à nouveau commande.

Le buste est travaillé en grandeur nature, cuit en argile rougeâtre. Les épaules sont recouvertes par la robe, le visage gracieux est tourné vers la gauche, avec une expression intelligente mais impassible. Les cheveux tombent en boucles sur les épaules.

Aucune identification n'a été faite jusqu'à présent.

Louise-Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755 Paris - 1842) compte également parmi les personnalités artistiques les plus importantes de son époque. Peintre et élève de Claude Joseph Vernet, elle avait elle aussi des liens étroits avec la cour, puisqu'elle était également l'épouse d'un descendant de Charles Lebrun, qui joua un rôle important en tant que peintre à Paris et Versailles à la cour de Louis XIV. Malgré les intrigues, elle fut admise à l'Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture grâce aux encouragements du roi et réalisa ensuite de nombreux portraits de la société de cour.

Ainsi, bien que de vingt ans plus jeune que Pajou, elle était en quelque sorte une collègue artiste. Cela explique qu'elle ait été portraiturée grandeur nature par Pajou, probablement à la suite de cette rencontre.

La ressemblance avec le petit buste en argile mentionné plus haut se rapporte à quelques similitudes, comme les boucles de cheveux, et surtout le visage ; cependant, le drapé de la robe est complètement différent ; au lieu du ruban oblique qui serre le torse à la manière d'une mode de jeunesse antique, c'est l'ourlet en dentelle du chemisier qui est montré ici, ce qui laisse supposer que le présent buste a été réalisé un peu plus tard. Selon la datation, la peintre est représentée ici à l'âge de 28 ans. A.R. (1370629) (11)

* Source et infos complémentaires : Hampel - Munich, vente du 28 septembre 2023

___________________

L'expert aurait pu se fendre d'une photo, ou d'une référence, dudit "buste entré sur le marché de l'art" grâce auquel il avance cette attribution du modèle.

Pour quelles raisons le sculpteur aurait réalisé deux bustes de la peintre la même année ? Les traits de l'une sont-ils tout à fait ceux de l'autre ??

Madame Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), peintre

Augsutin Pajou

Terre cuite, 1783

Au revers, sur le renfort dorsal : "Pajou. fe. 1783."

Salon de 1783, n° 218. Le marbre daté de 1785 et ayant figuré au Salon de 1785 a disparu

Hauteur : 0,555 m ; Largeur : 0,445 m ; Profondeur : 0,21 m ; Hauteur avec accessoire : 0,705 m

Image : RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / René-Gabriel Ojéda

Images : RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / René-Gabriel Ojéda

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

J'ai une réplique, (estampillée Pajou !) chez moi !

Je l'avais achetée, (il y a longtemps ) sur un coup de cœur en entrant chez un antiquaire à Villeneuve les Avignon. je l'avais ramenée en Tgv...

Je l'avais achetée, (il y a longtemps ) sur un coup de cœur en entrant chez un antiquaire à Villeneuve les Avignon. je l'avais ramenée en Tgv...

_________________

"Je sais que l'on vient de Paris pour demander ma tête ! Mais j'ai appris de ma mère à ne pas craindre la mort, et je l'attendrai avec fermeté !"

Marie Antoinette

attachboy- Messages : 1492

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

attachboy a écrit:J'ai une réplique, (estampillée Pajou !) chez moi !

Je l'avais achetée, (il y a longtemps ) sur un coup de cœur en entrant chez un antiquaire à Villeneuve les Avignon. je l'avais ramenée en Tgv...

Magnifique !

_________________

« elle dominait de la tête toutes les dames de sa cour, comme un grand chêne, dans une forêt, s'élève au-dessus des arbres qui l'environnent. »

Comte d'Hézècques- Messages : 4390

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Age : 44

Localisation : Pays-Bas autrichiens

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Pour une fois, il ne s'agit pas d'un de ses selfies célèbres autoportraits...

Prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères ce qui serait donc un portrait de...

Prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères ce qui serait donc un portrait de...

Madame Vigée Le Brun Seated in a Garden Reading a Letter

Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine (1751-1824)

Black chalk with stumping, heightened with white, 1783

bears the artist's initials in black ink, lower left: L.M.

signed and dated in pen and brown ink on the lower right edge of the mount (bearing the collector’s mark ARD, Lugt 172): Lemoine dess. 1783.

498 by 416 mm

Exhibited : Paris, Hôtel Villayer, Salon de la Correspondance, 26 March 178 (...)

Catalogue Note

Jacques Antoine-Marie Lemoine’s large scale portrait drawing of Madame Vigée Le Brun, seated in a garden, reading, is a sumptuous feast for the eyes. Not only is it triumphant in execution, but it is equally successful in its embodiment of the French dix-huitième image; one that invokes the extravagance and splendour of the Rococo epoch.

The portrait is one of a series of portraits en pied (full-length portraits) that Lemoine produced during the early 1780s. Until Neil Jeffares’ catalogue of Lemoine’s work, published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1999, very little had been written on the artist’s life and career.

In his opening lines, Jeffares noted the admiration in which Lemoine was held by serious, esteemed collectors and connoisseurs, including Marius Paulme, who once owned this exquisite portrait (see provenance) and the Goncourt brothers, who revered his work, but remarked that despite this no substantial review of the artist’s work had previously been attempted.(1)

A certain ambiguity surrounds Lemoine’s training and tutelage. Born in Rouen in 1751, he is often recorded as having been a pupil of Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1704-1788), but accounts differ as to when he is supposed to have entered La Tour’s Paris studio, and there is no concrete evidence to substantiate any working relationship. All the same, Jeffares rightly points out La Tour’s evident stylistic influence on Lemoine’s mature work, especially in the ‘remarkable intensity of the sitter’s gaze captured in so many of his portraits.(’2) While La Tour excelled as a pastellist, Lemoine’s skills and talent were, however, far more apparent in his portrait drawings, of which this is a paramount example.

The tangible textures created by Lemoine in the present work are extraordinary, illustrating his deftness in handling chalk. With great variety of pressure and subtle stumping throughout, accompanied by the skilful application of white heightening, he has achieved a diversity of tones and textures that clearly differentiate the landscape from the figure of Madame Vigée, while still maintaining total visual harmony.

As Jeffares noted in his Dictionary of Pastellists, the specific type of chalk that Lemoine employed was of the greatest significance to him. The livret published to accompany the Salon of 1796 describes the medium used by Lemoine in one of his exhibits as ‘crayon noir-de-velours de la composition du citoyen Coiffier, rue de Coq Saint Honoré’.

Although Lemoine at this stage clearly utilised the chalk produced by the luxury papetier René Coiffier, even this seems not to have met with his total satisfaction, and he took to manufacturing his own materials, which he advertised in a handbill entitled: Manufacture de crayons artificiels / De J.A.M. Lemoine, Peintre, rue J-J Rousseau.(3) The booklet elaborates on the type of product available, and its capabilities: ‘les crayons dit de Sauce, pour Estompe, remplacement ceux dits de Velours et n'en ont pas le défaut de graisser ni d'empâter l'Estompe.’(4) There could be no better example than the present work to illustrate how vital the composition of the chalk was to Lemoine’s ability to create textures, through immensely subtle blending and stumping of the medium. Here in this magnificent portrait, these techniques are given full rein, especially in the passages were the artist mimics the sheen of satin across the surface of his sitter’s dress or creates believable textures in the foliage of the lush garden setting.

Prior to embarking on his more ambitious and large-scale portraits en pied, Lemoine’s drawings were mainly in the same format as the fashionable portrait engravings of the day, which were mostly oval or circular, in profile, with decorative borders. Lemoine’s 1778 portrait of Rosalie Duthé, seated in front of a mirror at her dressing table, marked the beginning of the artist’s exploration of more elaborate compositions and settings for his protagonists.(5) These grand portraits, as Jeffares observes, concentrated more on complex effects of materials, and concentrated on composition rather than on facial expression.(6) Another portrait of Mlle Duthe tenant une harpe, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, demonstrates Lemoine’s concern with the overall composition and accompanying decorative elements and objects, here the harp and furniture, which have become perhaps more important than obtaining a true likeness of his sitter.(7)

Lemoine’s portrait of Madame Vigée Le Brun, executed in 1783 and exhibited in the same year at the Salon de Correspondence (alongside works submitted by Madame Le Brun herself), portrays the artist at the age of twenty-eight, seated in a garden, intently reading a letter, the contents of which were clearly so interesting that she has raised her free hand in reaction. A closed garden gate (perhaps symbolic) is visible to the left of the composition and a potted plant sits atop a rocky outcrop on the right. The scene is one that is familiar in the history of art and many analogies can be made with other images of women portrayed in a garden and/or reading letters. Perhaps the most relevant comparisons here are with works by other French eighteenth-century artists, notably Boucher’s renowned portraits of Madame de Pompadour and Fragonard’s series of elegantly attired women in satin dresses. Lemoine continued to explore this genre, exhibiting two more portraits later that same year in the Salon of 1783; Une femme dans le desespoir, and Femme satisfaite.8 The artist continued to develop his ideas in this genre of portraiture up until 1791.

The luxury and intimacy of this exceptional portrait encourages us to explore the relationship between artist and sitter. Jeffares, in his 1999 publication, alludes to the fact that Lemoine exhibited his pastels and chalk drawings at the premises of the dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, who was Madame Le Brun's husband, but it is not clear if this working relationship led to Lemoine actually meeting Madame Vigée.(9) The two artists did, however, both depict a number of the same sitters, including Mmes Dugazon, Duthé, Saint Huberty, Gramont-Caderousse and Molé, and this may also have provided the occasion for them to meet. Furthermore, Jeffares discusses the links that both Lemoine and Madame Le Brun had with the Le Couteulx family.(10) Although the exact circumstances under which the present work was undertaken remain uncertain, Lemoine and his sitter clearly came into contact in various ways. The happy outcome was this ravishing portrait, which captures all the opulence of its time, and also Madame Le Brun’s own allure and beauty, widely recognized by her contemporaries, and abundantly evident in the artist’s own self-portraits.

Madame Vigée Le Brun was a remarkable eighteenth-century figure and a brilliantly accomplished artist, whose works of all types are celebrated in this sale: from her portraits, in oil and pastel, of members of the aristocracy, her chalk and pastel studies of young infants and children, and her outstanding Self-portrait in Traveling Costume, to her evocative and acutely modern landscapes. This portrait by Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine is a fitting tribute to the extraordinarily talented Madame Vigée Le Brun and encapsulates the imagery that defines 18th-Century French art.

Notes

1 N. Jeffares, ‘Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine (1751-1824)’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, February 1999, p. 61

2 Ibid, p. 62

3 N. Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, under Jacques Antoine-Marie Lemoine, p. 1

4 Ibid

5 N. Jeffares, op. cit., 1999, cat. no. 21, reproduced

6 Ibid., p. 64

7 Ibid., cat.no. 27, reproduced p. 64, fig.1

8 Ibid., cat. nos. 45 and 46

9 Ibid., p. 65

10 Ibid

* Source et infos complémentaires : Sotheby's - New York, vente du 31 janvier 2024

Madame Vigée Le Brun Seated in a Garden Reading a Letter

Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine (1751-1824)

Black chalk with stumping, heightened with white, 1783

bears the artist's initials in black ink, lower left: L.M.

signed and dated in pen and brown ink on the lower right edge of the mount (bearing the collector’s mark ARD, Lugt 172): Lemoine dess. 1783.

498 by 416 mm

Exhibited : Paris, Hôtel Villayer, Salon de la Correspondance, 26 March 178 (...)

Catalogue Note

Jacques Antoine-Marie Lemoine’s large scale portrait drawing of Madame Vigée Le Brun, seated in a garden, reading, is a sumptuous feast for the eyes. Not only is it triumphant in execution, but it is equally successful in its embodiment of the French dix-huitième image; one that invokes the extravagance and splendour of the Rococo epoch.

The portrait is one of a series of portraits en pied (full-length portraits) that Lemoine produced during the early 1780s. Until Neil Jeffares’ catalogue of Lemoine’s work, published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1999, very little had been written on the artist’s life and career.

In his opening lines, Jeffares noted the admiration in which Lemoine was held by serious, esteemed collectors and connoisseurs, including Marius Paulme, who once owned this exquisite portrait (see provenance) and the Goncourt brothers, who revered his work, but remarked that despite this no substantial review of the artist’s work had previously been attempted.(1)

A certain ambiguity surrounds Lemoine’s training and tutelage. Born in Rouen in 1751, he is often recorded as having been a pupil of Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1704-1788), but accounts differ as to when he is supposed to have entered La Tour’s Paris studio, and there is no concrete evidence to substantiate any working relationship. All the same, Jeffares rightly points out La Tour’s evident stylistic influence on Lemoine’s mature work, especially in the ‘remarkable intensity of the sitter’s gaze captured in so many of his portraits.(’2) While La Tour excelled as a pastellist, Lemoine’s skills and talent were, however, far more apparent in his portrait drawings, of which this is a paramount example.

The tangible textures created by Lemoine in the present work are extraordinary, illustrating his deftness in handling chalk. With great variety of pressure and subtle stumping throughout, accompanied by the skilful application of white heightening, he has achieved a diversity of tones and textures that clearly differentiate the landscape from the figure of Madame Vigée, while still maintaining total visual harmony.

As Jeffares noted in his Dictionary of Pastellists, the specific type of chalk that Lemoine employed was of the greatest significance to him. The livret published to accompany the Salon of 1796 describes the medium used by Lemoine in one of his exhibits as ‘crayon noir-de-velours de la composition du citoyen Coiffier, rue de Coq Saint Honoré’.

Although Lemoine at this stage clearly utilised the chalk produced by the luxury papetier René Coiffier, even this seems not to have met with his total satisfaction, and he took to manufacturing his own materials, which he advertised in a handbill entitled: Manufacture de crayons artificiels / De J.A.M. Lemoine, Peintre, rue J-J Rousseau.(3) The booklet elaborates on the type of product available, and its capabilities: ‘les crayons dit de Sauce, pour Estompe, remplacement ceux dits de Velours et n'en ont pas le défaut de graisser ni d'empâter l'Estompe.’(4) There could be no better example than the present work to illustrate how vital the composition of the chalk was to Lemoine’s ability to create textures, through immensely subtle blending and stumping of the medium. Here in this magnificent portrait, these techniques are given full rein, especially in the passages were the artist mimics the sheen of satin across the surface of his sitter’s dress or creates believable textures in the foliage of the lush garden setting.

Prior to embarking on his more ambitious and large-scale portraits en pied, Lemoine’s drawings were mainly in the same format as the fashionable portrait engravings of the day, which were mostly oval or circular, in profile, with decorative borders. Lemoine’s 1778 portrait of Rosalie Duthé, seated in front of a mirror at her dressing table, marked the beginning of the artist’s exploration of more elaborate compositions and settings for his protagonists.(5) These grand portraits, as Jeffares observes, concentrated more on complex effects of materials, and concentrated on composition rather than on facial expression.(6) Another portrait of Mlle Duthe tenant une harpe, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, demonstrates Lemoine’s concern with the overall composition and accompanying decorative elements and objects, here the harp and furniture, which have become perhaps more important than obtaining a true likeness of his sitter.(7)

Lemoine’s portrait of Madame Vigée Le Brun, executed in 1783 and exhibited in the same year at the Salon de Correspondence (alongside works submitted by Madame Le Brun herself), portrays the artist at the age of twenty-eight, seated in a garden, intently reading a letter, the contents of which were clearly so interesting that she has raised her free hand in reaction. A closed garden gate (perhaps symbolic) is visible to the left of the composition and a potted plant sits atop a rocky outcrop on the right. The scene is one that is familiar in the history of art and many analogies can be made with other images of women portrayed in a garden and/or reading letters. Perhaps the most relevant comparisons here are with works by other French eighteenth-century artists, notably Boucher’s renowned portraits of Madame de Pompadour and Fragonard’s series of elegantly attired women in satin dresses. Lemoine continued to explore this genre, exhibiting two more portraits later that same year in the Salon of 1783; Une femme dans le desespoir, and Femme satisfaite.8 The artist continued to develop his ideas in this genre of portraiture up until 1791.

The luxury and intimacy of this exceptional portrait encourages us to explore the relationship between artist and sitter. Jeffares, in his 1999 publication, alludes to the fact that Lemoine exhibited his pastels and chalk drawings at the premises of the dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, who was Madame Le Brun's husband, but it is not clear if this working relationship led to Lemoine actually meeting Madame Vigée.(9) The two artists did, however, both depict a number of the same sitters, including Mmes Dugazon, Duthé, Saint Huberty, Gramont-Caderousse and Molé, and this may also have provided the occasion for them to meet. Furthermore, Jeffares discusses the links that both Lemoine and Madame Le Brun had with the Le Couteulx family.(10) Although the exact circumstances under which the present work was undertaken remain uncertain, Lemoine and his sitter clearly came into contact in various ways. The happy outcome was this ravishing portrait, which captures all the opulence of its time, and also Madame Le Brun’s own allure and beauty, widely recognized by her contemporaries, and abundantly evident in the artist’s own self-portraits.

Madame Vigée Le Brun was a remarkable eighteenth-century figure and a brilliantly accomplished artist, whose works of all types are celebrated in this sale: from her portraits, in oil and pastel, of members of the aristocracy, her chalk and pastel studies of young infants and children, and her outstanding Self-portrait in Traveling Costume, to her evocative and acutely modern landscapes. This portrait by Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine is a fitting tribute to the extraordinarily talented Madame Vigée Le Brun and encapsulates the imagery that defines 18th-Century French art.

Notes

1 N. Jeffares, ‘Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine (1751-1824)’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, February 1999, p. 61

2 Ibid, p. 62

3 N. Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, under Jacques Antoine-Marie Lemoine, p. 1

4 Ibid

5 N. Jeffares, op. cit., 1999, cat. no. 21, reproduced

6 Ibid., p. 64

7 Ibid., cat.no. 27, reproduced p. 64, fig.1

8 Ibid., cat. nos. 45 and 46

9 Ibid., p. 65

10 Ibid

* Source et infos complémentaires : Sotheby's - New York, vente du 31 janvier 2024

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Le fusain est de toute beauté

Le rendu de la soie de sa robe est phénoménal

Les lavis en second plan rendent bien la profondeur

Le rendu de la soie de sa robe est phénoménal

Les lavis en second plan rendent bien la profondeur

_________________

Un verre d'eau pour la Reine.

Mr de Talaru- Messages : 3193

Date d'inscription : 02/01/2014

Age : 65

Localisation : près des Cordeliers...

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Portrait of the Artist's Mother, Madame Le Sèvre, née Jeanne Maissin

Élisabeth Louise Vigée (later Madame Vigée Le Brun)

oil on canvas, an oval

canvas: 264.5 by 53.7 cm ; framed: 84.1 by 74.6 cm

Provenance :

Collection of the artist, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Paris (1842 inv.); Thence by inheritance to her niece, Baronne de Rivière (née Charlotte-Jeanne-Élisabeth-Louise ["Caroline"] Vigée; 1791-1864), Paris, Louvenciennes, and Versailles; Thence by descent until the second half of the nineteenth century, when sold to the Comtesse de la Ferronnays, née Marie-Louise-Guillemine Gibert (1819-1906) (...)

Catalogue Note

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun produced this elegant depiction of her mother at the outset of her career. The likeness, painted when the artist was around twenty years old, demonstrates her precocious talent and epitomizes the type of graceful society portrait that would soon come to define her artistic output.

Vigée Le Brun strikes a careful balance of immediacy and idealism in depicting her quadragenarian mother. Jeanne Maissin (1728-1800), with her body turned to the left, engages directly with the viewer. With sparkling gray eyes and gently flushed cheeks, she slightly parts her lips, as if about to speak.(1) Her lightly powdered gray hair is swept up stylishly, befitting a fashionable hairdresser.(2) She wears an elegant satin pelisse and loose coat trimmed with swan's down ("une pelisse de satin blanc bordée d'une fourrure de cygne"); the turquoise ribbon at her bosom matches the bow adorning her white cap. Vigée Le Brun's already expert use of luminous oil glazes enables her to render flesh, fabric, and fur with striking subtlety.

Born in Orgeo (in the Waloon region of the province Luxembourg) to Christophe Maissin, a well-to-do marchand laboureur, and his wife Catherine Grandjean, Jeanne married the pastel portraitist and member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, Louis Vigée (1715-1767) in 1750. (3)

The couple had two children: a daughter, the author of the present work, and a younger son, Louis Jean-Baptiste-Étienne, who became a successful playwright and poet. Following her first husband's death in 1767, Jeanne married Jacques François Le Sèvre, a jeweler and goldsmith from Savoy.

The artist’s stepfather, Jacques François Le Sèvre

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

ca 1774

Image : Commons Wikimedia

In Vigée Le Brun’s 'Souvenirs', written during the last decade of her storied life, the artist recalled having depicted her mother on at least three occasions: once in pastel in the costume of a sultana (lost) and twice in oil. In addition to the present work, Mademoiselle Vigée produced a bust-length view of her mother seen from behind (location unknown).(4)

With perhaps a nostalgic bent (or a touch of forgetfulness that comes with age), Vigée Le Brun indicated that all three works—as well as her Portrait of Étienne Vigée, signed and dated 1773—had been executed between 1768 and 1772, while she was still a teenager.(5)

The artist’s brother, Louis-Jean-Baptiste-Etienne Vigée

Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, post 1773

Image : The Frame Blog

Voir notre sujet : Etienne Vigée, le frère d'Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

More likely, the Portrait of the Artist’s Mother was executed circa 1778, soon after the less sophisticated likenesses of her step-father and brother. By then, the artist had joined the Académie de Saint-Luc and was on the cusp of success. Indeed, according to the artist, the present painting "made my reputation in society" and ensured her future fame: the duchesse de Chartres so admired the portrait that she commissioned her own from the young painter. (6)

Portrait of the duchesse de Chartres, née Louise-Marie-Adélaïde Bourbon Penthièvre (later the duchesse d'Orléans)

Oil on canvas

Private Collection, UK

Image : Commonw wikimedia

Vigée Le Brun prized the present painting, which hung in the sitting rooms of her Parisian apartment on the rue Saint-Lazare until her death. The portrait remained in the artist’s family, first passing to her niece-by-marriage, Baronne Jean-Nicolas-Louis de Rivière (née Charlotte-Jeanne-Élisabeth-Louise Vigée, nicknamed “Caroline"), until the mid-nineteenth century. The work was copied on at least three occasions: once in 1842 by Vigée Le Brun’s niece-by-marriage, Élisabeth Françoise "Eugénie" Tripier Le Franc (1797-1872) and much later twice by René-Louis Damon, for the descendants of the painter’s brother's daughter, "Caroline" de Rivière.(7) Until the present work reemerged at Sotheby’s, Monaco, in 1985, it was thought to have been lost or destroyed during the nineteenth century.

Notes

1) On the open-mouthed smile in many of Vigée Le Brun's portraits, see C. Jones, The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris, Oxford 2014.

2) According to Barthélemy Mouffle d'Angerville, she was a "coëffeuse celèbre." See Mémoires secrets pour servir à l'histoire de la République des Lettres, vol. XXII, London 1784, p. 103.

3) On Louis Vigée, see N. Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, Louis VIGÉE (pastellists.com), updated 29 October 2023; see lot 13 in the present catalogue.

4) The work, previously attributed to Antoine Watteau, is reproduced in J. Baillio, “Quelques peintures réattributées à Vigée Le Brun,” in Gazette des Beaux-Arts 99 (January 1982), p. 16, fig. 4.

5) As is especially common for women artists, early in her career, Vigée Le Brun turned to her family members as ready models. In addition to Étienne (depicted in oil, fig. 2; and in pastel [private collection]), she also painted her step-father (private collection).

6) “me fit connaitre dans le monde.” Vigée Le Brun, leather-bound batch of the autograph manuscript of the artist's Mémoires (Rochester, New York, University of Rochester, Rush Rhees Library, CX103).

7) One of the latter copies was at one time the property of the owners of the Château de Saint-Fargeau (department of l'Yonne).

* Source et infos complémentaires : Sotheby's; New York, vente du 31 janvier 24

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Savez-vous la signification de l'épitaphe sur la tombe d'EVL : "Ici enfin je repose"?

_________________

"Le 7 de septembre, le roi a été heureusement purgé d'humeurs fort âcres, et de beaucoup d'excréments fermentés, en dix selles."

Journal de santé de Louis XIV

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Y aurait-il un second degré ?

Monsieur de la Pérouse- Messages : 504

Date d'inscription : 31/01/2019

Localisation : Enfin à bon port !

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Non, c'est une question que je me pose. Est ce EVL qui a souhaité cet épitaphe? On sent une certaine lassitude, un endroit où se poser après son émigration.

_________________

"Le 7 de septembre, le roi a été heureusement purgé d'humeurs fort âcres, et de beaucoup d'excréments fermentés, en dix selles."

Journal de santé de Louis XIV

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Oui, l’Emigration… sans compter les chagrins que lui causèrent sa fille et qui assombrirent la seconde partie de sa vie !

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11796

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Enfin enterrée à Louveciennes elle n’avait plus à fuir elle qui pendant une longue partie de sa vie fut une véritable nomade européenne en comptant la Russie.

C’est vrai que les soucis d’avec sa fille ont dû la fatiguer.

Je pense plutôt pour la première solution

C’est vrai que les soucis d’avec sa fille ont dû la fatiguer.

Je pense plutôt pour la première solution

_________________

Un verre d'eau pour la Reine.

Mr de Talaru- Messages : 3193

Date d'inscription : 02/01/2014

Age : 65

Localisation : près des Cordeliers...

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Je viens de finir la lecture de cet intéressant petit livre La tombe de Mme Vigée-Lebrun à Louveciennes de Albert Vuaflart (Hachette livre BnF).

On apprend que c'est bien l'artiste qui a demandé l'inscription: "ICI, ENFIN JE REPOSE!" sur son testament:

"Je veux être enterrée au Calvaire et, pour tout monument, une colonne de marbre où sera un bas-relief gravé, une palette avec les pinceaux avec ses mots: Ici, enfin je repose; au dessous mes nom gravés ou sculpter. Je désire un enterrement simple ".

Le Calvaire est celui du Mont-Valérien. Mais, suite à la Révolution de 1830, les inhumations se firent de plus en plus rares. Ainsi, l'artiste modifia son testament:

"Comme il ne m'est plus possible de me faire enterrée au Calvaire, je recommande à ma nièce Caroline de Rivière, née Vigée, ma légataire universelle, de me choisir une place dans le cimetière de Lucienne et, pour tout monument, une colonne ou un piédestal sur lequel elle fera sculpté en bas-relief une palette avec les pinceaux, au dessous ses mots: Ici, enfin je repose, plus bas mes noms (Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Lebrun). Le petit monument sera entouré d'arbres vert et fermer par une grille bronzé. Je désire un enterrement très simple, et que les pauvres du pays reçoive une somme de deux cents francs qui leurs sera partagée par ma nièce, en joint au Curé de Lucienne".

Il est à noter que l'emplacement actuel de la tombe n'est pas celle d'origine et que certains éléments tels la couronne de Laurier et le soleil, ont été ajoutés plus tard.

Il est dit que cette épitaphe ne renvoie pas à la vie mouvementée de l'artiste mais à un hommage à sa passion de peindre.

La deuxième partie du livre concerne le tableau de Sainte Geneviève visible dans l'église de Louveciennes dont le visage s'inspire du visage de la fille de l'artiste.

On apprend que c'est bien l'artiste qui a demandé l'inscription: "ICI, ENFIN JE REPOSE!" sur son testament:

"Je veux être enterrée au Calvaire et, pour tout monument, une colonne de marbre où sera un bas-relief gravé, une palette avec les pinceaux avec ses mots: Ici, enfin je repose; au dessous mes nom gravés ou sculpter. Je désire un enterrement simple ".

Le Calvaire est celui du Mont-Valérien. Mais, suite à la Révolution de 1830, les inhumations se firent de plus en plus rares. Ainsi, l'artiste modifia son testament:

"Comme il ne m'est plus possible de me faire enterrée au Calvaire, je recommande à ma nièce Caroline de Rivière, née Vigée, ma légataire universelle, de me choisir une place dans le cimetière de Lucienne et, pour tout monument, une colonne ou un piédestal sur lequel elle fera sculpté en bas-relief une palette avec les pinceaux, au dessous ses mots: Ici, enfin je repose, plus bas mes noms (Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Lebrun). Le petit monument sera entouré d'arbres vert et fermer par une grille bronzé. Je désire un enterrement très simple, et que les pauvres du pays reçoive une somme de deux cents francs qui leurs sera partagée par ma nièce, en joint au Curé de Lucienne".

Il est à noter que l'emplacement actuel de la tombe n'est pas celle d'origine et que certains éléments tels la couronne de Laurier et le soleil, ont été ajoutés plus tard.

Il est dit que cette épitaphe ne renvoie pas à la vie mouvementée de l'artiste mais à un hommage à sa passion de peindre.

La deuxième partie du livre concerne le tableau de Sainte Geneviève visible dans l'église de Louveciennes dont le visage s'inspire du visage de la fille de l'artiste.

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Merci M. de Coco pour ces précisions.

Voici ladite tombe, au cimetière de Louveciennes :

Image : Culturez-Vous - Marly Le Roi

Avec description et autres photos (notamment les décors gravés) ici :

Avec description et autres photos (notamment les décors gravés) ici :

Cimetières de France - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Cimetières de France - Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Voici ladite tombe, au cimetière de Louveciennes :

Image : Culturez-Vous - Marly Le Roi

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Julie Le Brun

Julie Le Brun

A tous les portraits de famille présentés dans mon précédent message, j'ajoute cet autre, celui de sa fille, prochainement présenté en vente aux enchères...

Portrait of the artist's daughter, Jeanne-Julie-Louise Le Brun (1780-1819), playing a guitar

Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (Paris 1755-1842)

oil on canvas

39 ½ x 32 5⁄8 in. (100.4 x 83 cm.)

Provenance :

(Probably) the painting listed in the 1842 inventory of the artist's estate, and by descent to her niece, Caroline Vigée de Rivière (1791-1864), Versailles.

Anonymous sale, Hotel Drouot, 10 March 1864, lot 1.

(Probably) Prince Sigmond Radziwilłł (1822-1892), Chateau d'Ermenonville; his sale, Hotel Drouot, Paris, 22 March 1866, lot 145 (1900 francs).

Arthur Veil-Picard (1854-1944), Paris,

Confiscated from the above following the Nazi occupation of France after May 1940 (ERR no. W.-P. 120),Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives section from the Altaussee salt mines and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 23 June 1945 (MCCP no. 341⁄2). Repatriated to France on 25 June 1946 and restituted on 11 October 1946.

(...)

Lot Essay

Jeanne-Julie-Louise Le Brun (1780-1819), called Julie, was the only child of Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748-1813) – the preeminent dealer, auctioneer and art expert in Paris during the final decades of the Ancien Régime – and Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of Europe’s most celebrated portraitists. Born in Paris on 12 February 1780, Julie was, like her mother, admired for her beauty from earliest childhood, adored for her large expressive blue eyes and cascades of thick brown hair, the source of her affectionate nickname, ‘Brunette’.

Vigée Le Brun painted the girl often throughout Julie’s childhood and adolescence, most famously in two double portraits featuring both mother and daughter in tender embrace. One of these self-portraits with Julie, known as ‘Maternal Tenderness’, dates from 1786 when the girl was six years old; the other from three years later.

Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille

1786

Image : Musée du Louvre

Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille

1789

Image : Musée du Louvre

Among the most beloved works in the Louvre, these canonical images of maternal love – although secular and entirely contemporary – were inspired by the artist’s intensive study of the ‘Madonna della Sedia’ and other depictions of the Virgin and Child by Raphael. Perhaps the most charming of Vigée Le Brun’s portraits are three of Julie executed in 1787 – one of the child resting her head on an open Bible (private collection), and two almost identical versions of seven-year-old Julie, with a kerchief tied on her head, gazing at her face in a mirror (one version, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wrightsman Collection; the other, private collection, New York).

Julie Le Brun Looking in a Mirror

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

1786 and 1787

Images : Metropolitan Museum of Art

A lovely (if erotically charged) portrait of Julie, aged twelve and on the cusp of womanhood, depicts her as a bather at a reed-filled woodland pool, Susanna-like in her surprise at the arrival of an unseen intruder (private collection). Executed in 1792, it was commissioned by the Russian collector Prince Nicolai Borisovich Yusupov.

Julie Le Brun as a Bather

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

1792

Image : L'Art au présent / Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The present portrait of Julie playing the guitar dates from 1797-8, when the artist and her daughter were living in exile in St. Petersburg. Having fled France (accompanied by Julie’s governess) in 1789, they arrived in Russia in 1795, following long sojourns throughout Italy, Germany and Austria. Writing of their lives at the time that this painting was executed, Vigée Le Brun would recount in her memoirs (1835-7):

`My daughter had reached the age of seventeen. She was charming in every respect. Her large blue eyes sparkled with spirit, her slightly upturned nose, her pretty mouth, her beautiful teeth, a delicious freshness, all these features united to form one of the prettiest faces you could ever wish to see. She was not very tall, but slim, without being too thin. There was an air of natural grace about her person, yet this did not prevent her manner from being as lively as her mind. She possessed a prodigious memory and could recall everything she had learnt in her many lessons or from her reading. She had a charming voice and sang Italian marvelously, for I had secured the finest music masters for her in Naples and St. Petersburg as well as teachers of English and German. Furthermore she could accompany herself on the piano and guitar; but I was particularly charmed by her natural aptitude for painting, so all in all, I cannot say how delighted and proud I was of her many gifts.' (Souvenirs, 1835-7, chapter XXII; S. Evans, trans., p. 211)

In the portrait, Julie sits on a grassy knoll in a wooded glade. She casts her eyes upward for inspiration as she plays the guitar, the musical instrument at which, as her mother noted, she was expert. Her pretty face and the pale skin of her left arm and hand are highlighted by the warm afternoon sun. Her hair is tied up in a red scarf and she wears a loose-fitting white muslin dress cinched at the waist with a second red scarf – indeed, she is dressed in a Grecian style ‘a l’Antique’ that is almost identical to the costume her mother wore in the Louvre Self-Portrait with Julie of 1789. Wrapped over her arm and around her waist is a saffron-colored swag of drapery. Vigée Le Brun observed in her memoirs:

`As I had a horror of the current fashion, I did my best to make my models a little more picturesque. I delighted when, having gained their trust, they allowed me to dress them after my fancy. No one wore shawls then, but I liked to drape my models with large scarves, interlacing them around the body and through the arms, which was an attempt to imitate the beautiful style of draperies seen in the paintings of Raphael and Domenichino. Examples of this can be seen in several of the portraits I painted while in Russia; in particular, one of my daughter playing the guitar' (op. cit, Letter IV, p. 27).

As with the Portrait of Julie Looking in a Mirror, Vigée Le Brun made two autograph versions of the present composition. Joseph Baillio, the artist’s leading modern authority, believes it is the present version that Vigée Le Brun sent back to Paris for exhibition in the Salon of 1798; a second version today in the Zoubov Foundation Museum, Geneva, is of slightly later date and lacks the gold necklace that Julie wears here. The painting was retained by the artist throughout her life and is recorded in her estate inventory after her death in 1842.

Julie Le Brun jouant de la guitare (détail)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

huile sur toile, vers 1797-1798.

Image : Photothèque du MAH / via Ge.ch - Fondation Zoubov

The portrait also marks the last happy days in Julie Le Brun’s relationship with her mother. Shortly after it was completed, Julie fell in love with Gaétan Nigris, secretary to the Director of the Imperial Theatres in St. Petersburg. Against her mother’s wishes, Julie married the charming and handsome Nigris in 1799 – a man Vigée Le Brun described as `without talent, fortune or family' and accused of being a fortune hunter – and remained with him in Russia after her mother returned to Paris in 1801. It was to be a rift that would never entirely mend.

Although the young couple moved to Paris themselves in 1804, the marriage was not a success and they separated permanently four years later. When Julie’s father died in 1813 – almost two decades after divorcing the émigré Vigée Le Brun in 1794 on the grounds of desertion – he bequeathed his daughter his opulent townhouse in the rue du Gros-Chenet, along with his mountainous debts and obligations.

Julie as Flora, Roman Goddess Of Flowers

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1799

Image : St. Petersburg, Museum of Fine Art / Commons Wikimedia

When she died six years later, age 39, on 8 December 1819 – of uncertain cause; her mother claimed it was from smallpox, but it may have been pneumonia or syphilis – Julie was nearly destitute, having had to pawn nearly everything she owned, including her bed sheets and petticoats. Although Vigée Le Brun recounts a poignant deathbed reunion with her daughter, the present portrait – the last the artist would paint of Julie – commemorates the end of a loving bond that inspired many of her most enduring works of art.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's - New York, vente du 17 avril 2024

Portrait of the artist's daughter, Jeanne-Julie-Louise Le Brun (1780-1819), playing a guitar

Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (Paris 1755-1842)

oil on canvas

39 ½ x 32 5⁄8 in. (100.4 x 83 cm.)

Provenance :

(Probably) the painting listed in the 1842 inventory of the artist's estate, and by descent to her niece, Caroline Vigée de Rivière (1791-1864), Versailles.

Anonymous sale, Hotel Drouot, 10 March 1864, lot 1.

(Probably) Prince Sigmond Radziwilłł (1822-1892), Chateau d'Ermenonville; his sale, Hotel Drouot, Paris, 22 March 1866, lot 145 (1900 francs).

Arthur Veil-Picard (1854-1944), Paris,

Confiscated from the above following the Nazi occupation of France after May 1940 (ERR no. W.-P. 120),Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives section from the Altaussee salt mines and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 23 June 1945 (MCCP no. 341⁄2). Repatriated to France on 25 June 1946 and restituted on 11 October 1946.

(...)

Lot Essay

Jeanne-Julie-Louise Le Brun (1780-1819), called Julie, was the only child of Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748-1813) – the preeminent dealer, auctioneer and art expert in Paris during the final decades of the Ancien Régime – and Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), one of Europe’s most celebrated portraitists. Born in Paris on 12 February 1780, Julie was, like her mother, admired for her beauty from earliest childhood, adored for her large expressive blue eyes and cascades of thick brown hair, the source of her affectionate nickname, ‘Brunette’.

Vigée Le Brun painted the girl often throughout Julie’s childhood and adolescence, most famously in two double portraits featuring both mother and daughter in tender embrace. One of these self-portraits with Julie, known as ‘Maternal Tenderness’, dates from 1786 when the girl was six years old; the other from three years later.

Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille

1786

Image : Musée du Louvre

Madame Vigée-Le Brun et sa fille

1789

Image : Musée du Louvre

Among the most beloved works in the Louvre, these canonical images of maternal love – although secular and entirely contemporary – were inspired by the artist’s intensive study of the ‘Madonna della Sedia’ and other depictions of the Virgin and Child by Raphael. Perhaps the most charming of Vigée Le Brun’s portraits are three of Julie executed in 1787 – one of the child resting her head on an open Bible (private collection), and two almost identical versions of seven-year-old Julie, with a kerchief tied on her head, gazing at her face in a mirror (one version, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wrightsman Collection; the other, private collection, New York).

Julie Le Brun Looking in a Mirror

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

1786 and 1787

Images : Metropolitan Museum of Art

A lovely (if erotically charged) portrait of Julie, aged twelve and on the cusp of womanhood, depicts her as a bather at a reed-filled woodland pool, Susanna-like in her surprise at the arrival of an unseen intruder (private collection). Executed in 1792, it was commissioned by the Russian collector Prince Nicolai Borisovich Yusupov.

Julie Le Brun as a Bather

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

1792

Image : L'Art au présent / Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The present portrait of Julie playing the guitar dates from 1797-8, when the artist and her daughter were living in exile in St. Petersburg. Having fled France (accompanied by Julie’s governess) in 1789, they arrived in Russia in 1795, following long sojourns throughout Italy, Germany and Austria. Writing of their lives at the time that this painting was executed, Vigée Le Brun would recount in her memoirs (1835-7):

`My daughter had reached the age of seventeen. She was charming in every respect. Her large blue eyes sparkled with spirit, her slightly upturned nose, her pretty mouth, her beautiful teeth, a delicious freshness, all these features united to form one of the prettiest faces you could ever wish to see. She was not very tall, but slim, without being too thin. There was an air of natural grace about her person, yet this did not prevent her manner from being as lively as her mind. She possessed a prodigious memory and could recall everything she had learnt in her many lessons or from her reading. She had a charming voice and sang Italian marvelously, for I had secured the finest music masters for her in Naples and St. Petersburg as well as teachers of English and German. Furthermore she could accompany herself on the piano and guitar; but I was particularly charmed by her natural aptitude for painting, so all in all, I cannot say how delighted and proud I was of her many gifts.' (Souvenirs, 1835-7, chapter XXII; S. Evans, trans., p. 211)

In the portrait, Julie sits on a grassy knoll in a wooded glade. She casts her eyes upward for inspiration as she plays the guitar, the musical instrument at which, as her mother noted, she was expert. Her pretty face and the pale skin of her left arm and hand are highlighted by the warm afternoon sun. Her hair is tied up in a red scarf and she wears a loose-fitting white muslin dress cinched at the waist with a second red scarf – indeed, she is dressed in a Grecian style ‘a l’Antique’ that is almost identical to the costume her mother wore in the Louvre Self-Portrait with Julie of 1789. Wrapped over her arm and around her waist is a saffron-colored swag of drapery. Vigée Le Brun observed in her memoirs:

`As I had a horror of the current fashion, I did my best to make my models a little more picturesque. I delighted when, having gained their trust, they allowed me to dress them after my fancy. No one wore shawls then, but I liked to drape my models with large scarves, interlacing them around the body and through the arms, which was an attempt to imitate the beautiful style of draperies seen in the paintings of Raphael and Domenichino. Examples of this can be seen in several of the portraits I painted while in Russia; in particular, one of my daughter playing the guitar' (op. cit, Letter IV, p. 27).

As with the Portrait of Julie Looking in a Mirror, Vigée Le Brun made two autograph versions of the present composition. Joseph Baillio, the artist’s leading modern authority, believes it is the present version that Vigée Le Brun sent back to Paris for exhibition in the Salon of 1798; a second version today in the Zoubov Foundation Museum, Geneva, is of slightly later date and lacks the gold necklace that Julie wears here. The painting was retained by the artist throughout her life and is recorded in her estate inventory after her death in 1842.

Julie Le Brun jouant de la guitare (détail)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

huile sur toile, vers 1797-1798.

Image : Photothèque du MAH / via Ge.ch - Fondation Zoubov

The portrait also marks the last happy days in Julie Le Brun’s relationship with her mother. Shortly after it was completed, Julie fell in love with Gaétan Nigris, secretary to the Director of the Imperial Theatres in St. Petersburg. Against her mother’s wishes, Julie married the charming and handsome Nigris in 1799 – a man Vigée Le Brun described as `without talent, fortune or family' and accused of being a fortune hunter – and remained with him in Russia after her mother returned to Paris in 1801. It was to be a rift that would never entirely mend.

Although the young couple moved to Paris themselves in 1804, the marriage was not a success and they separated permanently four years later. When Julie’s father died in 1813 – almost two decades after divorcing the émigré Vigée Le Brun in 1794 on the grounds of desertion – he bequeathed his daughter his opulent townhouse in the rue du Gros-Chenet, along with his mountainous debts and obligations.

Julie as Flora, Roman Goddess Of Flowers

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1799

Image : St. Petersburg, Museum of Fine Art / Commons Wikimedia

When she died six years later, age 39, on 8 December 1819 – of uncertain cause; her mother claimed it was from smallpox, but it may have been pneumonia or syphilis – Julie was nearly destitute, having had to pawn nearly everything she owned, including her bed sheets and petticoats. Although Vigée Le Brun recounts a poignant deathbed reunion with her daughter, the present portrait – the last the artist would paint of Julie – commemorates the end of a loving bond that inspired many of her most enduring works of art.

* Source et infos complémentaires : Christie's - New York, vente du 17 avril 2024

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Elle était décidément aussi belle que sa mère. Quelle gâchis, quelle tristesse que sa fin...

Son portrait "surprise au bain" me gêne par contre et je reste surpris que l'artiste ait accepté ce genre de commande.

Son portrait "surprise au bain" me gêne par contre et je reste surpris que l'artiste ait accepté ce genre de commande.

_________________

J'ai oublié hier, je ne sais pas ce que sera demain, mais aujourd'hui je t'aime

Calonne- Messages : 1132

Date d'inscription : 01/01/2014

Age : 52

Localisation : Un manoir à la campagne

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Pourquoi cela ? C'est le plus craquant, peut-être mon préféré. Je le trouve pudique et d'une infinie tendresse toute maternelle.

_________________

... demain est un autre jour .

Mme de Sabran- Messages : 55509

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Localisation : l'Ouest sauvage

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Alors, je sais qu'il ne faut pas juger une période historique avec notre mentalité actuelle, que nos schémas de pensée actuels ne sont pas ceux de nos ancêtres.

Mais... Je suis mère et artiste, j'ai un type qui me commande un portrait de ma fille de douze ans les seins nus (enfin, partiellement cachés), je refuse et le type n'approchera jamais ma fille.

Après je sais, douze ans à l'époque n'étaient pas douze ans aujourd'hui et le rapport à l'âge n'était pas le même : les filles se mariaient vers 15 ans, avaient leur premier enfant vers 17 ans et se retrouvaient grand-mère à 35/40 ans.

Mais quand-même...

Mais... Je suis mère et artiste, j'ai un type qui me commande un portrait de ma fille de douze ans les seins nus (enfin, partiellement cachés), je refuse et le type n'approchera jamais ma fille.

Après je sais, douze ans à l'époque n'étaient pas douze ans aujourd'hui et le rapport à l'âge n'était pas le même : les filles se mariaient vers 15 ans, avaient leur premier enfant vers 17 ans et se retrouvaient grand-mère à 35/40 ans.

Mais quand-même...

_________________

J'ai oublié hier, je ne sais pas ce que sera demain, mais aujourd'hui je t'aime

Calonne- Messages : 1132

Date d'inscription : 01/01/2014

Age : 52

Localisation : Un manoir à la campagne

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

L’influence d’Angelica Kauffmann dans ces portraits exécutés lors de son émigration en Italie est frappante !

Gouverneur Morris- Messages : 11796

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Re: Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Calonne a écrit:Je suis mère et artiste, j'ai un type qui me commande un portrait de ma fille de douze ans les seins nus (enfin, partiellement cachés), je refuse et le type n'approchera jamais ma fille.

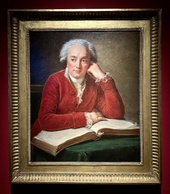

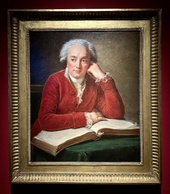

Portrait of Prince Nikolai Yossupov

Johann Baptist Lampi

oil on canvas, 1794

Image : Virtual Russian Museum, The St Michael’s Castle

Il faudrait reprendre les souvenirs de Mme Le Brun afin de savoir si elle évoque la commande de ce portrait ? Ils se sont sans doute croisés en Italie, du temps où elle s'y était réfugiée et lui en mission diplomatique. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun se rendra en Russie en 1795 seulement.

Princess Tatiana Vassilievna Youssoupov (1769-1841)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1797

Image : Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

Portrait of Boris Yusupov (1794-1849), as Cupid

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Oil on canvas, 1797

Collection privée

Image : Commons Wikimedia

La nuit, la neige- Messages : 18137

Date d'inscription : 21/12/2013

Page 6 sur 6 •  1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» Souvenirs - Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun

» Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

» Etienne Vigée, le frère d'Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

» Galerie virtuelle des oeuvres de Mme Vigée Le Brun

» Caroline Bonaparte, épouse Murat, grande duchesse de Berg puis reine de Naples

» Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, née Amy Lyons

» Etienne Vigée, le frère d'Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun

» Galerie virtuelle des oeuvres de Mme Vigée Le Brun

» Caroline Bonaparte, épouse Murat, grande duchesse de Berg puis reine de Naples

LE FORUM DE MARIE-ANTOINETTE :: La famille royale et les contemporains de Marie-Antoinette :: Autres contemporains : les femmes du XVIIIe siècle

Page 6 sur 6

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum